The Worst Street in London: Foreword by Peter Ackroyd (29 page)

Read The Worst Street in London: Foreword by Peter Ackroyd Online

Authors: Fiona Rule

In 1946, the National Insurance Act created a system of benefits to help those unable to work due to ill-health, redundancy, pregnancy or old age. Two years later, the National Health Service began providing free diagnosis and treatment. Finally, the long-suffering residents of Duval Street (and hundreds of other streets like it) could see a light at the end of a very long tunnel.

As we have previously seen, most residents of Duval Street, from the 1880s onwards were only there because they had nowhere else to go. Many were unable to work because they were either too old or mentally or physically sick. The creation of the NHS meant that these people could finally be correctly diagnosed and/or effectively helped. If treatment was not possible, then benefits were available to enable them to keep a decent roof over their heads and food in their stomachs. The mere fact that hospital beds were now free meant that many could finally leave the dreadful common lodging houses and seek medical help.

Of course, the creation of the welfare state did not completely solve the problem of the destitute poor. The common lodging houses still took in nightly lodgers and local prostitutes still required furnished rooms in which to ply their trade. However, the number of people requiring the services offered by the lodging-house keepers declined dramatically from the mid-1940s onwards.

By the 1950s, former common lodging houses that had been bursting at the seams during the winter months no more than 15 years previously, now had just a handful of tenants. The ever-enterprising landlords changed the usage of their property to adjust to the times. Former ‘thieves’ kitchens’ became tea rooms for office staff. Upstairs dormitories became brothels thinly disguised as private ‘gentlemen’s drinking clubs’. It was in one of these private establishments that a nightclub manager and possible descendent of landlord Johnny Cooney met with an ignominious end, thus bringing this story of the worst street in London back to where it began.

Selwyn Cooney was an ex-boxer who managed the Cabinet Club in Soho for gangland boss Billy Hill. A few days before the incident at the Pen Club in Duval Street described in the opening chapter, it is alleged that Cooney was involved in a fracas with North London gangsters the Nash brothers after an altercation with one of their girlfriends. Unfortunately, it seems that the fight did not clear the air and a few days later, Cooney ran into Jimmy Nash at the Pen Club. This time, it seems that Nash let his temper get the better of him and he pulled a gun on Cooney, shooting him at point blank range. In the ensuing mêlée, club owner William Ambrose (known as ‘Billy the Boxer’) was also shot at and wounded. Selwyn Cooney managed to stagger down the stairs and out into the street but collapsed on the cobbled, rain-soaked roadway.

Selwyn Cooney was the final person to die in Duval Street. Soon after his shooting, plans were drawn up by the council to create parking and loading bays for market lorries along the south side of the road and the remaining, squalid houses were served with demolition notices. Like the residents of the Flower and Dean Street rookery over 100 years before, the last residents of Duval Street disappeared into the shadows as silently and anonymously as they had arrived. By the mid-1960s, night-time in Duval Street was eerily quiet.

The London County Council changed their plans for the lorry park and erected a singularly unattractive, multi-story car park where the south side of Duval Street once stood. It is still there today and holds the dubious but fitting local reputation of being the most crime-ridden car park in London. As for Duval Street itself, the roadway still exists but all traces of ‘the worst street in London’ have been erased. The foundations on which once stood proud silk weavers’ homes, lively pubs and beer houses and squalid hovels like 13 Miller’s Court now lie under warehouse shutters and twenty-first century tarmac. Spitalfields as a whole is now a vibrant and fashionable place to live, work and play; the home of artists and artisans, just as it was when the Huguenots settled there.

Indeed, many of the streets and buildings that would have been familiar to the silk weavers are still standing. Hawksmoor’s masterpiece Christ Church still stands proudly at the top of Brushfield Street. Opposite, Spitalfields Market continues to trade albeit in fashion, jewellery and house wares rather than the previous commodities; the fruit and vegetable market moved out to larger premises in Leyton and is now the biggest horticultural market in the UK. Down in Brick Lane, the old Truman Brewery has suffered a similar fate as Spitalfields Market. It is now a complex of retail outlets, food stalls and event spaces. During the day, the area is bustling, hectic and colourful. However, as dusk falls, the streets take on a more sinister air, particularly the narrow alleyways that lead off the main thoroughfares. The seemingly indelible, sordid side of this fascinating part of London emerges from the darkness as the unknowing descendants of Mary Kelly, Mary Ann Austin and Kitty Ronan begin to ply their trade around the hallowed walls of Christ Church. Duval Street may have disappeared but its legacy is too powerful to ever be entirely erased.

A WALK AROUND SPITALFIELDS

Time:

Approximately one hour, allowing for a refreshment stop at the Ten Bells pub.

Start/End:

Liverpool Street Station (Metropolitan, Circle, Central and Hammersmith & City Underground Lines and Network Rail.)

NOTE: To make the most of your walk, book a tour of 18 Folgate Street and Christ Church. Contact details and further information can be found on the web at

www.dennissevershouse.co.uk

and

www.christchurchspitalfields.org

. Details of the different market days at Spitalfields Market can be found at

www.visitspitalfields.com

.

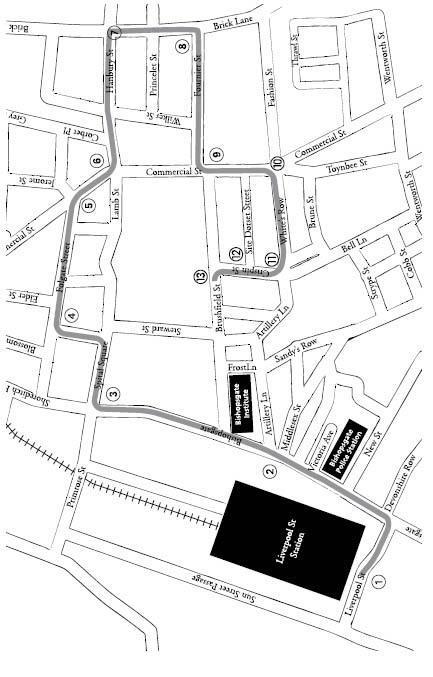

Start at Liverpool Street Station (Liverpool Street exit).

This station was opened in 1874, replacing the old Bishopsgate Station. It was built by the Great Eastern Railway’s chief engineer, Edward Wilson, and occupied a site where the Hospital of St Mary Bethlehem – Britain’s first psychiatric asylum – once stood. The chaotic and sometimes disturbing scenes witnessed by visitors to the hospital gave rise to the use of the word ‘Bedlam’ (a corruption of Bethlehem) to describe an uproarious scene. The hospital moved to Moorfields in 1676.

Turn left out of the station, then left into Bishopsgate. Walk past the police station and the Bishopsgate Institute (on your right.)

Cross the road and turn left into Spital Square.

This is where William Brune built his hospital in 1197. The Spital Field backed onto the grounds and was used by inmates as a source of pleasant views and fresh air. Today it is difficult to imagine this highly developed area as a rural retreat.

Turn left round Spital Square to Folgate Street.

Number 18 belonged to artist Dennis Severs until his death in 1999. Dennis came to London from the US in the 1970s and fell in love with Spitalfields. He managed to scrape together enough money to purchase this house and set about restoring it to reflect various periods in its history. The result is a truly unique experience where visitors feel they have stepped back in time. The exterior is a fine example of how the house would have looked when the Huguenot silk weavers populated the area. Tours of this fascinating house are available – go to

www.dennissevershouse.co.uk

for booking information.

Turn right into Folgate Street.

On the right is Nantes Passage, named after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which prompted the Huguenot silk weavers to come to Spitalfields.

Out onto Commercial Street.

The opposite side of the road was once a warren of streets that formed the northern edge of the ‘wicked quarter mile’ in the late 19th century. Much of the slum housing was demolished between 1922 and 1936 to make way for a massive tobacco factory, built for Godfrey Phillips and Son who had been trading in the area since the 1860s. The Royal Cambridge Theatre was also demolished during the redevelopment works. This theatre, known colloquially as the Cambridge Music Hall, was once a popular venue for performers such as Marie Lloyd and Marie Kendall. It stood roughly two thirds of the way down the factory façade. The building has now been divided up into retail, office and residential units.

Turn right and cross the road into Hanbury Street.

Many of the Spitalfields lodging housekeepers mentioned in The Worst Street in London also kept pubs. Johnny Cooney ran the Sugar Loaf at 187 Hanbury Street (a regular patron was his cousin, the music hall star Marie Lloyd) and the Weavers Arms at number 17. Prostitute Annie Chapman was murdered by Jack the Ripper in the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street (now demolished).

Walk along Hanbury Street to the corner of Brick Lane.

To the left is the Truman Brewery. The Truman family were associated with the area from the 1660s onwards. By the 19th century, the brewery was a major employer. It closed in 1988 and is now an office, shop and event complex.

Turn right down Brick Lane.

This was the home of Jimmy Smith, lodging house landlord, illegal bookie and police “fixer” who lived at 187 for much of his life. During the late 19th century, Jimmy was an influential resident responsible for bribing the local constabulary to turn a blind eye to illegal boxing bouts and dog fights. Jimmy evidently enjoyed his status as he would later tour his ‘manor’ in a chauffeur-driven Rolls-Royce – at the time, most Spitalfields residents rarely saw a motorcar, let alone one of such quality. Brick Lane was at the centre of battles between Eastern European Odessian and Bessarabian gangs at the turn of the century and was also the location of work premises kept by Jimmy Kray, grandfather to the infamous twins.

Stop at the corner of Brick Lane and Fournier Street.

The building on the right-hand side of the road was built by Huguenots in the early 18th century as a Protestant chapel. In 1898, it was converted into a synagogue, which closed in the 1970s and is now a mosque. This building provides a perfect example of the area’s constantly evolving social structure.

Turn right into Fournier Street.

There are some particularly good examples of 18th century silk weavers’ homes along this street. Look up to see the garrets where the looms once stood. There were many windows in the garrets so weavers could take advantage of the dimmest amount of light. Number 14 Fournier Street was built in 1726. The silk for Queen Victoria’s wedding dress was reputedly woven here. Fournier Street was known as Church Street until the end of the 19th century when the council saw fit to change the name in honour of George Fournier, a wealthy silk weaver, who had left a large bequest for the Spitalfields poor in his will.

Continue to the top of Fournier Street.

On your left is Christ Church, built by Wren’s protégé, Nicholas Hawksmoor, between 1714 and 1729. The church suffered a rather savage rehash of its interior in the 1850s and by the mid-20th century, it was in a very poor state of repair. However, in 2004, the church underwent a massive restoration project and now looks much as Hawksmoor had intended. Guided tours of the church are available – go to

www.christchurchspitalfields.org

for details.

To your right is the Ten Bells pub. Go inside and have a look at the original 19th century tiles on the walls, including a frieze showing 18th century silk weavers. By the late-19th century, this pub was at the epicentre of the ‘wicked quarter mile’ and was frequented by lodging house residents, market porters and prostitutes. Opposite the Ten Bells is Spitalfields Market. The market occupies what was originally the eastern edge of the Spital Field. There has been a market on this site since 1638 and the current building was opened in 1887. Spitalfields Market ceased to be a wholesale fruit and vegetable market in 1991. It is now a popular fashion and lifestyle market with numerous shops, cafes and specialist stalls. For full details of the different market days go to

www.visitspitalfields.com

.

Turn left along Commercial Street.