The Year Money Grew on Trees (8 page)

Read The Year Money Grew on Trees Online

Authors: Aaron Hawkins

***

We finished the last tree on March's final Saturday as the sky changed from blue into a pale pink sunset. I told everyone to wait while I ran back to my room to get my map of the orchard. We crossed off the few remaining trees and gave a little cheer.

"We're right on schedule. Can you believe it?" I asked giddily.

"So do we get paid now?" asked Michael.

Sometimes I couldn't tell whether he was serious.

"No, but I'm pretty sure the hardest part is over." Five pairs of eyes looked at me hopefully.

Learning to Drive

The relief of finishing the pruning was short-lived. After church on Sunday, all six of us went outside to the orchard to think about how to get rid of all the branches piled next to the trees. We had to assure my mom that we wouldn't be working, only thinking.

The orchard formed most of the view from the front door of my house. Out the back door was what my dad called "desolate land." It had some tumbleweeds, sagebrush, and wild grasses, but mostly it was rocks and dirt. If I went walking out there, my socks would always come back full of stickers and my mom would make me

sit outside and pull them out before I was allowed into the house. The desolate land must have been owned by Mr. Nelson, because when he was alive he would pile branches in random places on it. I had never realized where he was getting the branches until we started pruning.

"Let's just take the branches out there and leave them with the older ones. I wouldn't even ask Mrs. Nelson either," Amy said forcefully as we walked through the orchard inspecting piles.

Amy seemed so determined to avoid a conversation with Mrs. Nelson that I was afraid to question her. "Yeah, she probably isn't going to care, anyway," I said, "as long as we don't drag them through her yard."

"Drag them? I'm tired of dragging them!" Lisa yelled. "Plus, it's probably half a mile from here to where we could leave them. Dragging them could take the rest of the year!"

"That's not even close to half a mile," Sam said thoughtfully.

"More like a whole mile," said Michael.

We ended up walking off the distance to end the argument. The closest possible drop zone turned out to be about a hundred yards away.

Dragging a few branches at a time did seem like a very bad idea. I told everyone that we had no choice but to turn to our "secret weapon." I knew that we would

have to use it at some point, I just didn't realize it would be that soon.

Parked between my house and my cousins' house was a 1946 Ford tractor. Our families had never used it for anything agricultural. Mostly it was driven once or twice a year on what Uncle David called "hayrides." Everyone was forced to ride on a flat, rickety wagon attached to the tractor while it was pulled along the highway. No actual hay was involved. These trips usually took place around Christmas so we could look at and judge our neighbors' Christmas lights. Hayrides also took place around the Fourth of July, which seemed to be the only other time my dad or uncle remembered the tractor. Amy hated those rides and would duck her head when cars would drive by and complain about the splinters inflicted by the wagon.

Explaining where the tractor came from requires explaining my dad and uncle's one bedrock philosophy. It was something I grew up hearing at least once a week and was forced to repeat. In its simplest form it was this: No one should pay more than $300 for a car.

In order to live by this principle, each family had to have three cars. In the ideal case, two of the cars would be running at any given time. This would allow transportation options, while the third was cycled through for repairs. Often it was the other way around, though,

and one working car would have to spend its last few good miles searching for parts for the rest of the fleet.

Inevitably, my dad and uncle spent a lot of time fixing cars, and I wasn't sure they were all that good at it. Most every weekend was spent cursing carburetors, alternators, or fuel pumps. It was like a second job for both of them that they paid money to do and grumbled about the whole time. Besides fixing cars, they also spent a lot of time finding cars. That was how the tractor arrived.

My dad found someone selling a 1964 Plymouth Barracuda really cheap. When he went to look at it, he found that it didn't run but was pretty sure he knew what the problem was. The seller was willing to throw in the tractor for an extra $100 so that my dad could pull the Barracuda home. Eight hours later my mom was greeted by the sight of my dad on a tractor pulling another nonworking car. I was never sure where the wooden wagon came from. It just showed up one day.

My cousins, sisters, and I took a vote, and it was five to one in favor of using the tractor and wagon to haul the branches. Michael was against it because he just wanted to burn them. He had probably overheard my conversation with Tommy.

"Now we just have to convince our dads to let us use it and teach us to drive it," I said to everyone.

"Let me do the talking," Amy replied boldly. We found

both dads inside my uncle's house. He had bought a TV that came with a remote control, and they were both admiring it as we walked in the house.

"Watch how fast I can change the channels," said Uncle David as his thumb-clicked the little button as fast as it would go.

"You know, I'll bet this would be even more impressive if we got more than three channels." My dad laughed.

"All I really like to watch are football games and when they show movies, anyway," Uncle David responded defensively.

Amy went in and sat next to her dad.

"Can I try?" she asked, and he handed her the remote. "This is neat," she said after giving it a few clicks and handing it back.

"Daddy?" she asked.

"Yeah, honey?" he said, only half paying attention.

"Remember when you said you were going to teach me how to drive?"

"Uh-huh," he replied without taking his eyes off the TV.

"Well, I was thinking maybe you could show me how to drive the tractor to start, and then I could even use it to help out Jackson with his apple work."

Uncle David now turned his full attention to her.

"Huh? Now, what are you asking?"

"Can I learn to drive the tractor?" Amy repeated in her sweetest voice.

"And what are you planning on using it for?" asked my dad, who had now taken an interest in the conversation.

"If I can drive it, I was going to help out Jackson with his apples."

My dad and Uncle David both looked at each other. I could tell my dad wanted to say no. Uncle David, however, was thinking more about Amy, so he looked away from my dad.

"Well, I think that might be okay. You can't really go too far or too fast on a tractor," he said, looking at his daughter.

"Let's see if you can get it started first. That will prove you're ready to drive it," my dad added.

"Well, how do you start it?" Amy asked.

"We'll tell you, and you go see if you can get it running," my dad said with a little chuckle.

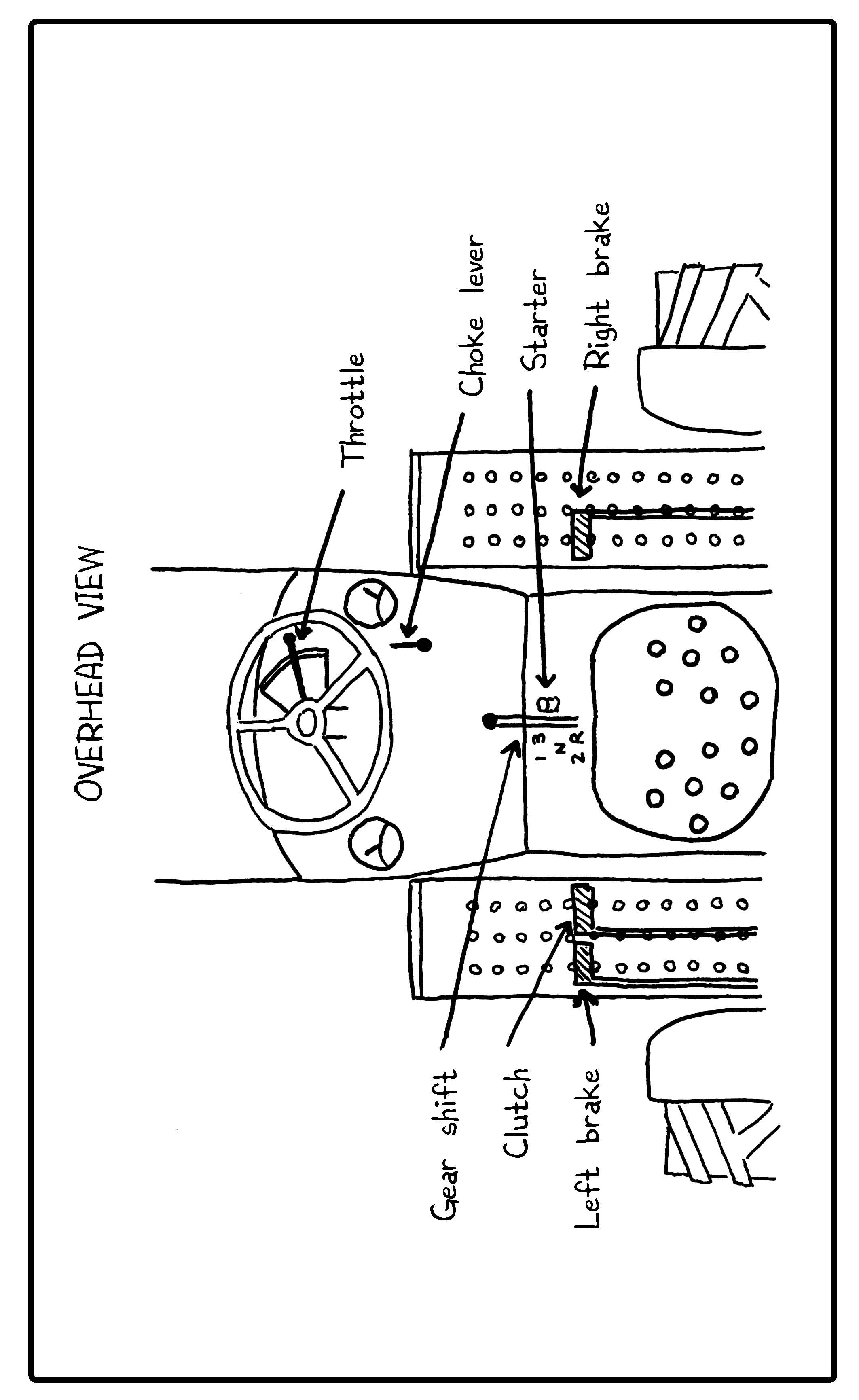

My dad and uncle began to describe things like "put it in neutral" and "pull the throttle all the way down" and "push in the starter button" and "push in the choke." All six kids listened closely, trying to remember all of the instructions.

"All right, you got all that?" They both laughed.

"Got it," Amy said confidently, and the rest of us kids followed her out of the house.

She led the way out to the tractor and climbed up on the bouncy metal seat while we all tried to stand behind her on the rear axle or on the running boards beside the seat.

"Okay, so what are we supposed to do first?" she asked as she grabbed the wheel.

"Put it in neutral," I replied before anyone else.

"Pull the throttle," said Lisa.

"Give it a choke," said Sam.

"Punch the starter," said Michael.

"All right, all right," Amy said, holding up her hands. "I'm not even sure what any of those things are!"

We sent the younger kids back into the house one at a time to ask where to find neutral, the throttle, choke, and starter. After fifteen minutes of confusing answers from our dads, we were ready to give something a try. We all held our breath as Amy reached toward the starter. I grabbed on to the metal wheel wells in case the thing lurched forward.

GRRR, GRRR, GRRR.

The tractor made the very familiar sound of a car not starting. I knew it could have been worse, though. It could have made no sound at all.

"Maybe now a little more choke," I said.

Amy pulled the little choke lever all the way out. "All right, it's all choked. What's a choke, anyway?"

"I don't think anyone really knows. Something magic," I replied.

This time when she pushed the starter, there was a little different sound. A slightly faster

GRRR.

On the third try the engine sputtered a little, trying hard to start.

"Try half choke, half throttle, and hold the starter down for a whole minute," Michael said matter-of-factly, as if he had started tractors hundreds of times.

"Let me go ask them," I said as I climbed down and walked toward the house.

I could tell my dad and uncle were enjoying this. Trying to get them to tell me the right combination of throttle and choke was like trying to get your lunch back from a couple of school bullies. Except that most school bullies are more sympathetic. I walked back to the tractor not sure if I knew any more than when I went into the house.

"Let's try throttle down and full choke. When it starts to turn over, push the choke in and give it full gas."

Amy tried and for a second the engine sputtered and blew out a puff of exhaust.

"I think I just have to be faster," she said before trying again.

Seven attempts later the engine was running. We all jumped up and down and cheered.

"Now go forward! Go forward!" Sam yelled above the motor.

Amy looked over her shoulder at me and mouthed, "Now what?"

I ran into the house and was told about a clutch and how you had to push it in and push the gear stick into gear. I relayed this information into Amy's ear, and she pushed the clutch with her left foot, shoved the stick into position 1, and then yanked her foot up off the clutch. The tractor jumped forward a few feet. Michael flew off the back axle and the engine died. This scene repeated itself several more times, except that Sam was the only one who dared stay on the tractor with Amy.

Finally she marched toward the house, gesturing for me to follow her. We both walked into the living room, where both my uncle and dad were fighting back laughter.

"Daddy, please just come show me how to get it to move once you get it started," Amy said with a pout, looking at her dad.

"Honey, you just have to let the clutch up a little slower. You'll get it."

Just then my aunt came into the room after realizing what was happening outside. She pointed a finger at my uncle and dad. "If they get that thing started and drive it into something or someone, I am holding you two knuckleheads responsible!"

Through the windows we heard the sound of the tractor starting up. Amy and I looked at each other and hurried toward the door, followed closely by our dads.

We arrived outside just in time to see Sam behind the

wheel and the tractor moving slowly forward. He was shouting triumphantly and turning onto the dirt road in front of our houses. Very quickly, he seemed to lose his nerve. I think he realized that he didn't know how to stop. He swerved toward our house, and the tractor rammed into the '64 Barracuda my dad had parked out front. Luckily it wasn't in working condition. The tractor sputtered to a stop, and Sam jumped off, his eyes wide.

There was some mild swearing from my dad and uncle. Then my uncle started laughing, probably because none of his cars were hit. My aunt kept repeating, "I knew this was going to happen." Surprisingly, our dads agreed to show Amy and me how to drive the tractor after that, including shifting into all the gears. I think they must have felt a little guilty. By the time it got dark, we could start it, back it up, and make all kinds of turns. There was something thrilling about going down a road in third gear at ten miles per hour, the wind not exactly blowing in your hair, but at least whispering in it.

***

Monday afternoon we drove the tractor and wagon into the orchard for the first time, barely missing trees as we pulled into the first row. We loaded up one and a half piles of pruned branches into the wagon, drove them out to the desolate land, and pushed them off next to some sun-bleached mounds of branches that looked

like they had been there for twenty years. After two or three rows, Amy and I had gotten pretty good at turning around trees and avoiding ditches. When it got dark, we left the tractor in the orchard for the night and headed home.

When we tried to start it the next day, it wouldn't turn over. We tried every combination of choke and throttle we could think of, but nothing seemed to work. Uncle David arrived home from work before my dad, and we begged him to come help us get the engine started again. After a few attempts of his own, he jumped off the bouncy metal seat.