This Is Your Brain on Sex (7 page)

Read This Is Your Brain on Sex Online

Authors: Kayt Sukel

Tags: #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology & Cognition, #Human Sexuality, #Neuropsychology, #Science, #General, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Life Sciences

Oxytocin is a bit of a wonder compound. Some even go so far as to say it is a little magical. Technically it is a neuropeptide, a small protein-like molecule that can act as a neurotransmitter, stimulating and inhibiting neurons in the brain. When released into the bloodstream, it has been implicated in such behaviors as milk letdown in nursing mothers, stimulation of uterine contractions during labor, and estrus cycle modulation. Pitocin,

a synthetic version of oxytocin, is used to help speed up labor during the birth process. Because of these maternal effects, researchers initially believed oxytocin to be a specifically female chemical, but the PVN and SON also send oxytocin directly into the brain’s cortex—in both males and females. In response to touch, sex, and social bonds, oxytocin stimulates cells in the ventral tegmental area. Once stimulated, these cells then initiate that lovely and agreeable dopamine cascade in the basal ganglia.

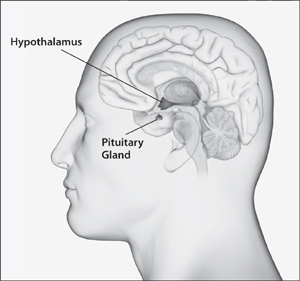

The hypothalamus mediates the release of oxytocin and vasopressin into both the body and the brain. The pituitary gland, the almond-shaped gland beneath the hypothalamus, releases other important hormones.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

“Oxytocin is a very important chemical. The brain is provided with its very own oxytocin system, that is very often activated in parallel to the circulatory oxytocin system,” explained Kerstin Uvnäs-Moberg, an oxytocin expert and the co-organizer of the original Wenner-Gren Symposium. She continues her work with oxytocin today at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and kindly offered to discuss the wonders of oxytocin with me over a crackly telephone line.

If you read the science news, it is hard to avoid oxytocin these days. Researchers across the globe are finding new ways in which oxytocin levels are positively influenced.

Activities like cuddling your baby skin-to-skin, hanging out with your dog, getting a massage, having orgasms, spending some time on the social networking site Twitter, or even experiencing simple eye contact with another person can amp up your oxytocin level. High levels of this neuropeptide have been associated with the ability to better read social nuance, increased trust and emotion, strong social bonds, and improved mood. On the other hand, if your oxytocin level is too low you may find it difficult to recognize faces, properly nurture your kids, or avoid cravings for salty and sweet foods. Social bonds, parent-child relationships, sexual behaviors, trust—oxytocin seems to play a role in all these complex behaviors and more. It is also now considered part of a potential treatment for autism, schizophrenia, and depression. Some “experts” have even proposed that it may be worthwhile to snort a little oxytocin to help bolster your mood and sociability before a date or job interview, though the majority of scientific researchers who study oxytocin would strongly argue against such a practice.

This is a chemical with extensive reach, yet its effects are quite subtle. When neuroscientists at Emory University used knockout techniques to remove the genes that produce oxytocin in mice, they thought they might find some changes in maternal behavior. Instead they learned that the lack of oxytocin in the medial amygdala region, a brain area rich in oxytocin receptors, made it so the animals could not recognize other mice. Their senses of smell and space were intact, as were their memories, yet knockout males could not recognize previously introduced females after thirty minutes apart, something normal mice can do without a problem. When the researchers injected these animals with oxytocin before the initial meeting, social recognition was restored.

5

In comparison, social recognition was also impaired when an oxytocin antagonist, a drug that stopped oxytocin from connecting with receptors, was injected into the medial amygdala of normal animals. It appears that the lack of oxytocin during the introduction interfered with encoding the appropriate social information about the female. This finding correlates with human studies. Scientists have shown that amygdala damage leads to problems with facial recognition, reading social cues, and expressing emotion. It makes sense. How can you form a bond, lasting or otherwise, with someone you do not even recognize at a second meeting?

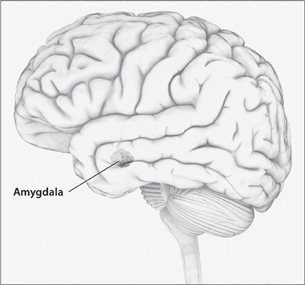

Lack of oxytocin in the amygdala has been linked to social recognition deficits.

Illustration by Dorling Kindersley.

Uvnäs-Moberg theorizes that this neuropeptide

is at the heart of a psychophysiological system that directly opposes the “fight or flight” phenomenon, which is an acute stress response mediated by activation in the hypothalamus, brain stem, and amygdala in response to situations that threaten survival. She proposes an analogous “calm and connection” response. Instead of accelerated heart rate, anxiety, and elevated glucose levels—the hallmarks of “fight or flight”—oxytocin helps mediate a contrasting circuit that results in relaxation, decreased heart rate, and an overall feeling of calm.

When you perceive a threat, you have to be prepared to act. Physiologically your body has to be at the ready to brawl or get the heck out of Dodge, and the response must be immediate. A physiological state of calm and connection does not require the same kind of speed. In the absence of danger you can take your time. Repeated administration of oxytocin has been shown to induce long-lasting effects to areas of the brain involved in social bonding, sexual behavior, and parental attachment. Over time this calm-and-connected state results not only in a feeling of high, as you might experience while in the throes of new love, but also in a general sense of relaxation and peace. That sense of well-being may have health benefits too. Many

studies have suggested that a calm demeanor and strong social relationships can help people weather stressful situations, fight disease, and even lengthen life. Add up these varying lines of research and you will find, Uvnäs-Moberg argues, a strong evolutionary advantage to a system antithetical to fight-or-flight. What’s more, she said, given its effects on the nervous system, oxytocin is qualified to be that agent of calm and connection in the brain.

6

Vivacious Vasopressin

Like oxytocin, vasopressin (more formally referred to as arginine vasopressin) is a small neuropeptide also released by the PVN and SON in the hypothalamus. It is very much like oxytocin; in fact the genes for both chemicals resides on the same chromosome. Their similarities are such that some scientists hypothesize the two may have evolved from a common compound a few hundred million years ago.

7

Vasopressin is involved with the regulation of blood pressure—hence

vaso,

indicating blood vessels. It is also implicated in kidney function, cell homeostasis, and glucose regulation. In the behavioral realm it is linked to attention, learning, memory, and aggression. Like oxytocin, it has a role in forming pair-bonds. It is a busy little bee of a neuropeptide.

If oxytocin was once thought of as a girl chemical, then vasopressin was its boy correlate; like oxytocin, however, vasopressin is present in both sexes. In prairie vole studies, infusions of vasopressin have been shown to increase territorial behaviors. Within a day of mating and bonding with a female, males will show heightened aggression; this newlywed will kill in order to make sure his lady, fertile and ready, will not be impregnated by a fellow suitor. Though slower to develop, aggression in females is also increased after they pair-bond. Other girls had better not even think of coming around their man. Not if they are keen on surviving.

Vasopressin is a difficult chemical to study, mainly because of its vast and various responsibilities throughout the body. This chemical is not unleashed just in the brain in response to sex but is also released in other parts of the body. Given its importance to heart and kidney function, it is not an element you want to knock out

completely in experiments, since you will end up with sickly, and probably dead, animals. To add another level of complexity, vasopressin can work with and against oxytocin. Each of these chemicals can bond with the other’s receptors, sometimes facilitating and sometimes blocking action. Researchers are still trying to tease apart their respective roles in the formation and maintenance of pair-bonds.

Some Other Key Players

Several other neurotransmitters have been implicated in love. Glutamate is a substance critical to learning and memory. Gamma-aminobutyric acid is a compound best known for inhibition (the damping down of overexcited neurons), as well as its effects on alertness and arousal. Both have been shown to be involved in reward pathways, but it is unclear how they interact with each other to result in love’s many behaviors. Studies are ongoing.

8

Serotonin, a neurotransmitter you may recognize for its importance in the treatment of depression, is also relevant when it comes to love. Although it is known for its mood-enhancing effects, serotonin levels actually drop in the early stages of love. This is a conundrum. Love makes you feel good, right? It enhances mood. Shouldn’t it make serotonin levels increase? But love also releases high amounts of dopamine. When dopamine goes up, serotonin goes down. It’s one of the ways the brain balances itself. Serotonin is often referred to as a brake, a way to stanch the dopamine flood so you aren’t always in thrall to those good feelings.

But love does more than just make you feel good. It also makes you a little obsessive—and obsession can be stressful. An early molecular study of love looked at the serotonin transporter, a small protein that helps serotonin get from place to place in the synapse. Donatella Marazziti, an Italian neuroscientist at the University of Pisa who studies love, compared the number of binding sites for the serotonin transporter protein in individuals who had recently fallen in love, individuals suffering from OCD, and normal, single controls. Marazziti and her colleagues found that the number of sites was significantly lower in both OCD patients and those in love. What

does this mean? Basically similar serotonin neurochemistry may have something to do with obsessive thoughts in both OCD and love. That same lack of serotonin that results in an OCD patient’s believing that touching a door five times upon entering can guarantee safety may also be behind the way you constantly, compulsively think about a new squeeze when you are in the honeymoon phase of a relationship.

9

You may have noticed that I have not mentioned estrogen or testosterone yet. One might think these gonadal hormones would play a strong role in love; after all, common knowledge suggests that all our love-related behaviors are driven by them. Perhaps you think estrogen is behind the desire to connect with your one true love. Though present in both sexes, it is often referred to as a female hormone and is characterized as the molecule that makes us vulnerable and open to others. When Marazziti and her colleagues at the University of Pisa measured hormone levels in individuals passionately in love, singletons, and those who had been in a committed relationship for some time, they saw no differences in estradiol, a form of estrogen, or progesterone, another so-called girlie hormone. What they did find was a heightened level of testosterone in women who were passionately in love and decreased levels of testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), a hormone linked to reproduction, in men. They also saw increased levels of cortisol, a hormone released in response to stress. When these passionately in love folks were retested one to two years later, all hormonal differences between the groups disappeared.

Why these levels changed in this manner is up for interpretation. Marazziti suggests the heightened cortisol levels represent arousal but also a certain amount of stress in the early days of a relationship. The idea fits with several animal studies demonstrating that being a little stressed out actually promotes social interaction and attachment. In animals a perceived threat is an incentive to band together. With a pal or pair-bonded mate around to help forage for food, take care of the young, and watch your back, the probability of survival increases dramatically.