This River Awakens (31 page)

Read This River Awakens Online

Authors: Steven Erikson

‘Unclip the first one there,’ he directed.

I did so, and leaned back as Walter turned the handle, keeping the cable straight as he walked me to him. We repeated the procedure with the second side cable.

‘Time to knock out the brakes,’ Walter said, grinning. He wore blue coveralls, grease-stained and threadbare. He squinted at me. ‘Is that a frown you’re wearing there?’

‘Sorry.’

‘Nervous?’

‘I guess.’

‘I packed us a lunch.’

‘Sea rations?’

‘God, no! A feast, my friend. Only the best for our inaugural voyage. You ready?’

‘Yep.’

His face bright, Walter took out a rag and wiped his hands. He tossed it to me and I did the same, though mostly the rag just spread the grease evenly over my hands. I tossed the rag back. He reached for it, missed, then bent down and picked it up.

He went to the tool-shed and returned with a mallet. ‘Good thing Reginald Bell’s on a supply run today.’

‘Are you going to get into trouble?’

‘Don’t worry. I’m not.’

The brakes were just wooden blocks set against the cradle’s steel wheels, each held in place with a steel pin. Walter pulled the pins out, then with an expert swing he knocked each brake out cleanly. The cable creaked with the third and then the fourth ones. ‘By the numbers, eh?’

I nodded.

‘We’ll need to fuel up. When she’s down at the waterline, take the line looped over the prow and secure it to the gas dock. Once she’s afloat, we can pull her alongside.’

‘Okay.’

Until this moment I don’t think I’d believed we’d actually get this far. Sometimes I’d suspected Walter was just humouring me, making all this into one of his tall tales. My heart pounded as I walked alongside

Mistress Flight

as she slowly backed down the rails to the river.

Walter stopped its progress when the muddy water lapped the base of the cradle. I clambered on to the frame and retrieved the line. The gas dock was to my left when facing the river. I carefully played the line out as I walked over to it. I secured it, then straightened and waved at Walter who still waited beside the main winch. He didn’t move. I waved again, both arms, but he still seemed to be waiting.

‘Okay!’ I called. ‘All secure!’

He gestured and then

Mistress Flight

edged into the water. Her stern settled alarmingly to my eyes, but finally rose just before her newly repainted name disappeared in the brown swirl. She rose free of the cradle, swung out into the current. I scrambled to make sure the line would hold, and watched as the woven rope lifted out of the water, pulling tight and shedding droplets as the current embraced the old yacht.

Walter reversed the winch, drawing the cradle back out of the water. He’d said he was going to leave it on the rails up top, moving it aside tomorrow. We wanted as much daylight as possible.

I stood on the gas dock, studying how she rode the water. She was beautiful, her new trim gleaming, sitting even and high. It was a few minutes before I realised that Walter stood beside me.

I sighed. ‘Yeah.’

‘You said it. Let’s haul her in and secure the stern line. Nice knot you managed there. Just like I showed you. We’ll fill the tanks and then see what the old Sea Horse can do, eh?’

II

‘As the crow flies, it’s about sixteen miles to the locks. Of course, we’ll be doing some twists and turns.’ Gribbs cocked his head. ‘See any company?’

‘Nope.’

‘Feel ready to take the wheel?’

‘Sure.’ The boy moved up beside him. ‘Stick to the middle, right?’

‘As simple as that.’

Owen set both hands on the chrome-plated wheel, spreading his legs wide. Gribbs stepped back to give him room.

‘Let’s play a game,’ he said.

‘What kind of game?’

‘Stay at this speed. Stay in the middle. The game’s called

What can you see?

Pretend I got a blindfold on. All I can feel is the wind through the ports. All I can hear is the Sea Horse. I’ve got a blank space in my head and it needs filling. It’s up to you to fill it. What you choose to tell me is all I’ll have to go by. What you choose to tell me shapes my picture. But so does what you choose not to tell me. If you tell me everything, I might get confused. If you don’t tell me enough, I might misunderstand. Same for if you tell me the wrong things.’

‘How do I know if I’m doing it right? How can some things be wrong?’

‘Because you paint my picture before I do. But it’s more than just a picture. You’ll see after we’ve been playing for a while.’

The boy was silent for a few minutes. Gribbs sat back, reaching into the backpack and removing his Thermos. He poured a cup. ‘Want some Coke?’

‘Sure.’

Gribbs pulled a can from the bag and handed it over. Owen pulled the ring off with a snap and a hiss. He swallowed a mouthful, then set the can down on the teak surface on the other side of the wheel.

‘The water’s red and brown,’ he said slowly. ‘It’s not flat, even though there’s no real wind. It’s, uh, it’s spreading out around us, bulging in places, rising up from underneath. It twists on itself, too. You can see it because of the sunlight. The sunlight shows you the shape of the water. Its surface. But you can’t see into the water. It’s too muddy, and the sunlight only lives on the surface. Am I doing it right?’

Gribbs smiled. ‘You tell me, son.’

‘I’m doing it right. I started in the right place. It starts with the river—’

‘It’s a river?’

‘The sunlight follows the current. The water spreads out from under us, but it follows its own path, and we’re being carried along. But it doesn’t care about us. It’s chosen its path all on its own. It doesn’t need to be seen to be there.’

‘You sure about that?’

‘Yes. It carries stuff all the time. Dead stuff, lost stuff. It carries … uh…’

‘What?’

‘Uh, history, I guess.’ He drank some more Coke. ‘A river. The river. Over it, over us, is the sky. Blue and no clouds at all. Just blue and the sun. It’s got nothing to tell us. It’s background, it’s what’s behind everything else. It doesn’t tell us anything, it just shows us what we need to see.’

‘Excellent. Go on.’

There was a growing excitement in the boy’s voice, and an undercurrent of tension. ‘I keep seeing too much. I have to keep closing it down. I have to decide what’s important.’

‘What’s important? Remember, you’re not just giving me the gift of your eyes, you’re also giving me the gift of your mind.’

‘Are you going to take your turn?’

‘When you’re done. Now, I see a brown river, and a blue, cloudless sky.’

‘You must see more than that! After all I’ve described!’

Gribbs smiled and sipped his tea. ‘Oh yes, but you’re not done yet. I want to hear your voice, not mine.’

‘The river spreads out to its banks. It was higher a while ago. But now it’s pulled back, shrunken. You can see what it once covered. The clay is brown – no, grey. Sometimes the sunlight shows it blue. The clay looks smooth, but scarred. Cracked, maybe. Too far away to be sure.’

‘Use your mind and take me there.’

‘It’s cracked, drying up, but that’s just the top layer. Like a skin. And you can also see that the skin was once wet. There’s bird tracks in it.’

‘Birds?’

‘Birds.’ Owen fell silent.

Gribbs cocked his head.

Something important here.

‘Birds,’ Owen said again. ‘They’re everywhere. They talk for the world. They talk with their voices for every tree they find. They talk the distance between trees, with their voices and with their wings. They scream when against the blue background. But when they’re on the river, they’re silent.’

‘Birds,’ Gribbs said, nodding.

‘Gulls. White and blue and grey, but mostly white. With hooked yellow beaks. They say nothing on the river. They just ride the current, and watch. Their heads never stop turning. The birds in the trees are different, smaller. They’re just shadows, like they’re showing the meaning of something – of movement! Not in words, not in talking aloud, just in what they are. Birds. They map the world, I think.’

‘You think?’

‘No. I’m sure. But the river just carries them, and they stay silent – not always, but mostly. And the others stay on the banks, in the trees. They mark the river’s flow, but stay in one place. So that’s how your world is mapped. How your picture is painted.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You don’t?’

‘No. There’s some things we don’t have to know about. We don’t always have to know why. Noticing’s enough. Sometimes it’s too much.’

‘Is it too much this time?’

‘They’re silent on the river. The river says enough, because it’s there and doesn’t care if we’re here or not. The birds know it, and that’s all they need to know.’

‘Do the birds care if we’re here or not?’

‘I think so. I think they watch us for the river.’

‘Is my picture complete?’

‘No. I have to talk about the trees. They’re small, starting partway up the bank. Bushy, lots of twigs, lots of leaves, as if they’re in a hurry. The bigger trees are inland a ways, past the bushes, the thickets, the bracken.’

‘Bracken?’

‘Sure. That’s a word.’

‘I know. Go on.’

‘It’s all dying.’

Gribbs sat up. ‘What?’

‘You can’t see it, but you know it.’

‘Owen—’

‘No. There’s people. Right now there’s none in sight. But their current rides under the river. Hidden, the water black and poison. And the roots of the trees – their hold is desperate, but hopeless. The people are here, and they won’t be stopped. They come with fire, and steel. The sunlight never shines on them – it just blinds them. They’re burning out the roots, pulling down the trees. The birds scream against the blue backdrop. None of it is here, in front of your eyes. It’s behind. It’s underneath, in between.’

‘Jesus, son—’

‘But the river stays silent. The people can’t hear it. They refuse to believe it doesn’t care about them. To it, we’re not giants, and maybe one man can become bigger. Maybe one man can come to mean more than he ever realised, but it’s only so in the heads of others. We’re smaller than we think, smaller than we’d dare admit—’

‘What the hell have you been reading?’

‘It doesn’t matter. We’re on the river, that’s all we need to know. There’s docks now. Wood. Grey. And parts of the bank are clear, grass lawns. There’s porches and houses, and sheds, and boats pulled up on the clay, or tied to docks. There’s a road, and two cars, one behind the other. The river feels wrong under us. It knows where it’s heading. People have thrown a wall across it, and it’s about to roar.’

‘In anger?’

‘Oh no. Just talking for the world. We never listen. We never really listen.’

‘Can you see the locks?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Throttle up and swing us around. I’ll drop the anchor and we can have lunch.’

‘Is the game over?’

‘Is it?’

‘I’m not sure.’

Gribbs shrugged. ‘Me neither.’

‘I realised something,’ Owen said.

‘What?’

‘You’re going blind, aren’t you?’

Gribbs smiled.

‘And that’s why I’m here.’

‘Oh, more than just that, my friend. After lunch, it’s my turn.’

‘I didn’t think I’d get scared playing that game.’

‘Same here.’

III

‘The taste of smoked salmon is exactly the same as its colour,’ I said.

‘Never thought of it that way,’ Walter said around a mouthful. ‘You might be right.’

We didn’t say anything for a few minutes, too busy eating. Smoked salmon, cream cheese, bagels, French bread, Stilton cheese, prosciutto ham and watered red Portuguese wine. I’d never tasted any of it before, and it made me realise just how boring my family’s own fare was.

Taste should be a surprise,

Walter had explained.

Each bite should cut across the palate, go in a different direction. Texture’s highly underrated in this country’s cuisine.

The wine was so heavily watered I barely felt it, but it swept everything clean between each bite of food. My head swam with the newness of it all.

‘You know,’ I said after a while, ‘I don’t know if I really see the world that way.’

‘Oh?’

‘I mean, I was painting you a picture, right? Just one kind of picture. I could’ve painted others.’

Walter nodded. ‘I believe you. Even so, it pulled you in, didn’t it? Hell, it pulled me in, that’s for sure.’

‘Summer’s almost over. I can’t believe how fast it went. The way my friends talked about it before school ended, I sort of pictured … something different, I guess. A wildness, as if the world was going to go back in time, as if the forests were going to fill with old, cold-eyed gods. And the ground under us moving ever so slightly, because the dwarves and demons were restless. Ever read

Beowulf?

’

‘What?’

‘It’s a poem.’

‘I know. You want to hear some of it? In Anglo-Saxon?’

I nodded, then said, ‘Yes.’

‘I’ve only heard it, mind you. Spoken. There was a man, once, a sea dog with his head full of old North Sea shanties and a whole lot more besides. Every time we ended up working alongside each other, he’d start. Reeling off lines, whole poems. Sometimes in Old French, or in High German, or Gaelic. Sometimes I didn’t recognise the language at all. It took me a long time to realise he was handing them down to me, passing them on, the same way someone had done to him when he was young. The man couldn’t read, couldn’t write, but he was an artist. In the old way.’

‘A bard.’

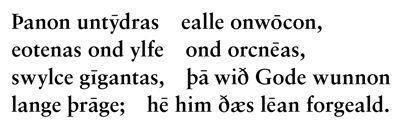

Walter grinned, then he cleared his throat and said,