Three Brothers

This book is a work of fiction.

Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 by Peter Ackroyd

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company.

Originally published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus, an imprint of the Random House Group Limited, London, in 2013.

DOUBLEDAY is a registered trademark of Random House LLC. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House LLC.

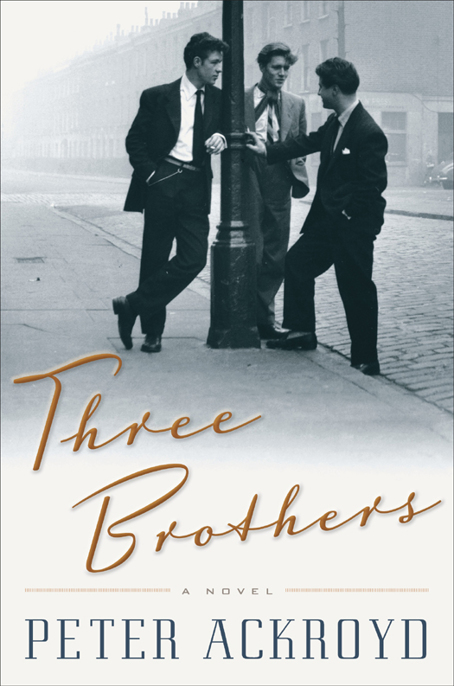

Jacket photograph © Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ackroyd, Peter, 1949–

Three brothers : a novel / Peter Ackroyd. — First American edition.

pages cm

Originally published in Great Britain by Chatto & Windus, an imprint of the Random House Group Limited, London, in 2013—Title page verso. 1. Brothers—Fiction. 2. City and town life—England—London—Fiction.

3. London (England)—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6051.C64T48 2014

823’.914—dc23

2013033737

ISBN 978-0-385-53861-9

ISBN 978-0-38553862-6 (eBook)

Contents

XV Don’t stick it out like that

Cheese and pickle

I

N THE

London borough of Camden, in the middle of the last century, there lived three brothers; they were three young boys, with a year’s difference of age between each of them. They were united, however, in one extraordinary way. They had been born at the same time on the same day of the same month—to be precise, midday on 8 May. The chance was remote and even implausible. Yet it was so. The local newspaper recorded the coincidence, after the birth of the third son, and the Hanway boys became the object of speculation. Were they in some sense marked out? Was there some invisible communion between them, apart from their natural affinity?

The interest soon subsided, of course, in a neighbourhood where the daily struggles of existence were still evident four or five years after the War. In any case, there were other differences between the boys—differences of temperament, differences of affection—that soon became manifest. These diversities, however, were still mild and pliable. They had not yet become the source of great disagreement or hostile division.

The three boys were young enough, and near enough in age, to enjoy the same pastimes. On the pavement outside

their small house in Crystal Street they chalked the squares of hop-scotch. They played marbles in the gutter with fierce concentration. They hardened the seeds of the horse chestnut with pickle juice and brine, so that they could compete with conkers. They raced each other on the common, at the edge of the council estate in which they lived. They explored the deserted tracts of land beside an old railway line, and trod cautiously among the debris of an abandoned bomb shelter.

On the common, too, they played the old game “Run Run Away.” One of them, with a scarf wound about his eyes as a blindfold, repeated a few well-known words as the others ran as far as they could; when he stopped speaking, they had to remain quite still. He then had to find them, and the first one he touched became “it” when the whole game began again.

On one particular afternoon the youngest of them, Sam, was standing, his eyes blindfolded, and he began to shout out the words.

“When I was standing on the stair

I met a man who wasn’t there.

He wasn’t there again today.

I wish, I wish he’d go away.

Here I come, ready or not!”

After a minute or two of threshing around he caught hold of his oldest brother, Harry. But there was no real excitement in the game. They had played it too often.

“Listen,” Sam said, “what do you both want to be when you grow up?”

“I want to be a pilot.”

“I want to be a detective.”

“Do you know what?” Sam told them. “I don’t want to be anything.”

The sky was growing darker, and a cold breeze had started up across the common with the promise of light rain. “Come on,” Harry said, pointing to the abandoned bomb shelter, “let’s

all go under the ground. I’ve got some matches. We can start a fire. Mum won’t miss us till teatime. Let’s start a fire that will go on

for ever

!”

“I dare you.”

“I double dare you.”

So one by one, in single file, following each other, they descended into the earth.

They had a small back garden, in which they investigated the lives of earwigs and other insects. At the bottom of this garden there was an old stone basin often filled with rainwater, and in this they raised tadpoles caught from the pond on the edge of the common. They put their heads together and peered down into the murky water, their sweet liquorice breath mingling with the dank odour of moss and slime. They tried to grow beans and peas in the garden, but the shoots withered and rotted away. It was, in short, a London childhood. They had never seen mountains or waterfalls, of course, but they lived securely in their world of brick and stone.

They recognised by instinct the frontiers to their territory; a street further north, or further south, was not visited. It was not welcoming. But within their own bounds they were entirely at home. They knew every dip in the pavement, every front door, every cat that prowled along the gutter or slumbered on the window sill. They knew, or at least recognised, most of the people they saw. There were few strangers in the neighbourhood. They lived among familiar faces.

Any stranger who happened to walk through the neighbourhood would not have come away with any distinct impression. It was a council estate, built in the 1920s, of two-storey red-brick terraces. That was all. One row of houses was interrupted by some small shops—a newsagent, a hairdresser, a butcher among them—and on the corners of the narrow streets were general stores or public houses. There was a fish-and-chip

shop, and a bakery, in the street where the Hanways lived. The district smelled at various times of dust and of rain, of bonfire smoke and of petrol. Its sounds were not of cars but of trams and milk-floats, with the distinct but distant roar of London somewhere around the corner. It had the forlorn calm of a poor neighbourhood, yet for the three brothers it repaid the closest possible attention. It was the source of curiosity, of surprise, and, sometimes, of delight. The centre of their lives was very small, but it was brightly lit. And all around stretched the endless streets, of which they were largely unaware.

Their first memories of childhood differed. Harry recalled how he had managed to walk unaided across the carpet of the small living room, praised and encouraged by his parents sitting on a yellow sofa. Daniel, between his brothers in age, remembered being taken out of a pram and held up to the sunlight, in which he seemed to soar. Sam’s first memory was of falling and cutting his leg on a shard of broken glass; he had cried when he saw the blood. Had their respective memories ever come together, they might have had some understanding of their shared past. But they were content with these fragments.

They attended the same primary school, a red-brick building set beside a grey-brick church, where the signs for “Boys” and “Girls” were carved in Gothic script above two portals. The school smelled of soap and carbolic disinfectant, but the classrooms were always cluttered and dirty with a faint patina of dust upon the shelves and windows.

The Hanway boys were in separate classes, according to their age, and in the playground they did not care to fraternise. Harry was the most gregarious and thus the most popular of the brothers; he laughed readily, and had a circle of acquaintances whom he easily amused. Daniel had two chosen friends, with whom he was always deep in consultation; they collected bus numbers and cigarette cards, which they would compare

and contrast. Sam, the youngest, seemed content to remain on his own. He did not seek the company of the other children. And they in turn left him alone. But Sam had a temper. One morning, at the gate of the school, a boy remarked on the fact that Sam had torn his school jacket. Sam struck out at him with his fist and knocked him to the pavement. His two brothers witnessed the event, and adjusted to him accordingly.

Harry Hanway was ten, Daniel Hanway was nine, and Sam Hanway was eight, when their mother disappeared. They returned late one afternoon from school, and found an empty house. Harry made sandwiches of cheese and pickle. They sat around the kitchen table, and waited. No one came.

Their father, Philip, was employed as a nightwatchman in the City. He always left the house in the afternoon, stopped at a pub on Camden High Street, and then took the bus to the financial headquarters where he worked. He would put on his dark blue uniform, kept in a small locker off the main hall, and then sit behind an imposing central desk. He always had with him pencils and paper. After a few minutes of concentration he would begin writing, slowly and hesitantly; then he would stop altogether. For the rest of the night he would smoke and stare into space.

He had been called up for the army, in the third year of the War, but in fact travelled no farther than Middlesbrough where he was assigned to the barracks as a clerk of munitions. He remained in that post until the end of the War when, with army pay in his pocket, he returned to London. He had been brought up in Ruislip, but he had no intention of returning. Ruislip was the place where he had waited impatiently for his real life to begin. Instead he set off for Soho. He believed that he was destined to be a writer. When he was a schoolboy, he had read an English translation of

The Count of Monte Cristo

over several weeks; he had devoured it, page by page, elated

and terrified by the turns of the plot. The day after he finished the novel, he began his own story. He never completed it. He put the pages in a biscuit tin, where at the time of this narrative they still lay. Yet he was not discouraged. He began writing other stories, to which he could never find a satisfactory conclusion. The more disappointment he suffered, the more intense his ambition became. He recalled the last words of

The Count of Monte Cristo

, “wait and hope.”

So he migrated to Soho in search of publishers, of magazines, of fellow writers, of critics, of any stimulus—he was not sure of his way forward. He rented a small room in Poland Street, and indulged in what seemed to him to be the bliss of bohemian life. He woke late; he drank coffee in dirty cafés; he lounged and sipped Guinness in shadowy pubs. Yet he could not write. He sat down at the folding table in his room, pencil in hand. He could find no subject.

When his army funds were low, he sought work in the neighbourhood. He became a barman in the Horn of Plenty, a pub in Greek Street that was the chosen spot for a group of hard-drinking and sometimes bellicose Soho residents. Philip Hanway was happy here. He called himself a writer, and enjoyed the anecdotes of the journalists and advertising copy-writers who frequented the bar. And then he met Sally Palliser. She worked in a cake shop, or “pâtisserie,” in Meard Street. He had passed its window, with a display of almond tarts and buns and pastries, and had seen her delicately picking out an angel cake for a customer. His first impression was of the graceful way she moved behind the counter, her skirt slightly creasing as she bent forward. On the following morning he paused, opened the gaily painted door, and ordered a macaroon. He purchased a macaroon every morning for the next few weeks.