Three Weeks With My Brother (26 page)

Read Three Weeks With My Brother Online

Authors: Nicholas Sparks,Micah Sparks

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography

Yet that day for whatever reason, Chinook stumbled.

I was in the kitchen of my apartment as the phone rang. When I answered, my father sounded breathless, on the verge of hyperventilating.

“Your mom’s been in an accident . . .” he started. “She fell off the horse . . . They took her to UC Davis Medical Center . . .”

“Is she okay?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know.” His voice was simultaneously panicked and robotic. “I had to bring the horses back. I haven’t talked to the doctor . . . I’ve got to get down there . . .”

“I’m on my way.”

Cathy and I drove to the hospital, terrified, and trying to convince ourselves that it wasn’t serious. As soon as we rushed into the emergency room, we asked the nurse in charge what was going on.

After checking her notes and heading back to talk to someone, she rejoined us.

“Your mother’s in surgery,” she said. “They think she ruptured her spleen. And her arm might be broken.”

I sighed with relief; I knew that though the injuries were serious, they weren’t necessarily life-threatening. A moment later, Mike Marotte, an old friend from high school who was on the cross-country team with me, hurried through the door.

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

“I was running on the trail when I saw a group of people and recognized your dad. I helped him get the horses back, and came straight to the hospital from there. What’s happening with your mom?”

Mike, like all my friends, loved my mom and seemed as frightened as I was.

“I don’t know,” I said. “They said she ruptured her spleen, but no one’s come out to talk to me. You were there though? Was it serious? How was she?”

“She wasn’t conscious,” he said. “That’s all I know. The helicopter got there just a couple of minutes after I did.”

The world seemed to be whirling in slow motion.

“Is there anything you need me to do? Can I call anyone?”

“Yeah,” I said. I gave him the phone numbers of relatives on both my mom’s and dad’s sides. “Tell them what happened, and tell them to call everyone else.”

He jotted down the numbers.

“And find Micah,” I said. “He’s supposed to be flying in from Cancun this afternoon. He’s coming into San Francisco.”

“What airline?”

“I don’t know.”

“What time is he coming in?”

“I don’t know. Do what you can . . . And find Dana, too. She’s in Los Angeles with Mike Lee.”

Mike nodded. “Okay,” he said. “I’ll take care of it.”

My dad arrived a few minutes later, pale and shaking. I told him what I knew, and he burst into tears. I held him as he cried, and a moment later he was mumbling, “I’m okay, now. I’m okay,” trying to stop the tears.

We took a seat, and minutes passed without a word. Ten. Twenty. I tried to look through a magazine, but couldn’t concentrate on the words. Cathy sat beside me, her hand on my leg, then she moved closer to my father. He sat and rose and paced, then sat again. He rose and paced, then sat again.

By then, forty minutes had gone by, and no one knew what was going on.

Micah had just stepped off the plane when he heard his name being paged over the public-address system at San Francisco International Airport, requesting him to answer the courtesy phone.

“Please go directly to UC Davis Medical Center,” the voice on the other end told him.

“What’s going on?”

“That’s all the message says.”

Suddenly panicked, he jumped into a limousine—no cabs were available—to take him to a friend’s house, where he’d left his car for the week.

He was two hours from Sacramento.

After an hour, a soft-spoken man wearing a suit came out to greet us.

“Mr. Sparks?”

We all rose, wondering if he was the doctor. He said that he wasn’t.

“I work with the hospital as a counselor,” he said. “I know this is hard, but please come with me.”

We followed him into a small waiting room; we were the only family in the room. It seemed it had been set aside for us. It was oppressive; I felt my chest constrict, even before he said the words:

“Your wife has suffered a cerebral hemorrhage,” he said to my father. His voice was gentle and ached with obvious sympathy.

Tears welled again in my father’s eyes. “Is she going to be okay?” my dad whispered. His voice began growing softer; I could hear the plea contained within it. “Please . . . please . . . tell me she’s going to be okay . . .”

“I’m so sorry,” the man said, “but it doesn’t look good.”

The room began to spin; all I could do was stare at him.

“She’s not going to die, is she?” I croaked out.

“I’m so sorry,” he said again, and though he stayed with us, I don’t remember him saying anything else. All I remember is suddenly reaching for Cathy and my dad. I drew them tight against me, crying as I’d never cried before.

Dana had gotten the call; she was boarding the next plane to Sacramento. I called a couple of relatives and told them what was happening; one by one, I heard them burst into tears and promise to be there as fast as they could.

Minutes crawled by, as if we were inhabiting a time warp. The three of us broke down and tried to recover again and again. An hour passed before we were able to see my mom. When we went into the room to see her, oxygen was being administered and she was receiving fluids; I could hear the heart machine beeping steadily.

For just a moment, it looked as if she were sleeping, and despite the fact that my mind knew what was happening, I nonetheless grasped at hope, praying for a miracle.

Later that evening her face began to swell. The fluids were necessary to keep her organs from being damaged in the event we would donate them, and little by little, she looked less like my mom.

Some of the relatives had arrived, and others were on the way. All had been in and out of the room but no one could stay very long. It was unbearable to be with my mom because it wasn’t her—my mom had always been so full of life—but it seemed wrong to stand in the hallway. Each of us drifted back and forth, trying to figure out which alternative was less terrible.

More relatives arrived. The hallway began to crowd with friends as well. People looked to each other for support. I didn’t want to believe what was happening; no one wanted to believe it. Cathy never left my side and held my hand throughout it all, but I felt myself constantly being pulled back to my mother.

When no one was in the room, I entered and closed the door behind me. All at once, my eyes welled with tears. I reached for her hand and felt the warmth I always had. I kissed the back of her hand. My voice was ragged, and though I’d already cried for most of the afternoon, I simply couldn’t stop when I was with her. Despite the swelling, she looked beautiful, and I wanted—with all my heart and soul, and more than I’ve ever wanted anything—simply for her to open her eyes.

“Please, Mama,” I whispered through my tears. “Please. If you’re going to come out of this, you’ve got to do it soon, okay? You’re running out of time. Please try, okay . . . just squeeze my hand. We all need you . . .”

I lowered my head to her chest, crying hard, feeling something inside me begin to die as well.

Micah arrived, and as soon as I saw him I burst into tears in his arms. Dana arrived an hour after Micah did, and had to be supported as she moved down the hallway toward us. She was wailing; hers were the tears of someone not only losing a mother, but her best friend as well. In time, my brother and I led her into the room. We’d warned her about the swelling, but my sister broke down again as soon as she saw how bad it had become. My mother looked unreal, a stranger to our eyes.

“It doesn’t look like mom,” she whispered.

Micah held her tight. “Look at her hands, Dana,” he whispered. “Just look at her hands. Those haven’t changed. You can still see mom right there.”

“Oh, Mama . . .” she cried. “Oh, Mama, please come back.”

But she couldn’t respond to our pleas. My mom, who had sacrificed so much in her life, who had loved her children more than any mother could, whose organs would go on to save the lives of three people, died on September 4, 1989.

She was forty-seven years old.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia

February 6

A

fter two days in Angkor we flew back to Phnom Penh, this time for a tour of the Holocaust Museum and a trip to the Killing Fields.

The museum is located in downtown Phnom Penh, which had been seized by the Khmer Rouge in 1975. Pol Pot, the leader of the Khmer Rouge, hoped to create a perfect communist state, and evacuated the entire city. A million people were forced into the countryside. With the exception of Khmer Rouge soldiers, whose average age was twelve, Phnom Penh became largely a ghost town.

With the departure of U.S. forces from Vietnam and no other country willing to intervene, Pol Pot began his bloody reign. His first act was to invite all the educated populace back into the city, upon which he promptly executed them. Torture became a way of life and death for thousands. In time, to save the cost of bullets, most of the executions were carried out by striking the victim on the back of the head with thick bamboo poles. Over the next few years, more than a million people were killed, either through enforced hardship, or executions in what are now known as the Killing Fields.

On the flight, Micah and I anticipated our arrival with a degree of ambivalence. Though we wanted to see both the museum and the Killing Fields, our excitement was tempered by our apprehension. This, unlike so many of the sites, wasn’t part of ancient history; it was modern history, home to events that people want to forget despite knowing that they never should.

From the outside, the Holocaust Museum looked unremarkable. A two-story, balconied building set off the main road, it resembled the high school it had originally been. But belying its innocuous appearance was the sinister barbed wire that still encircled it; this was the place where Pol Pot tortured his victims.

Our guide, we learned, had attended school there, and it felt disconcerting, almost surreal, when he pointed to his former classroom, before moving us to the exhibits.

They were a series of horrors: a room where they used electricity to torture victims; other rooms featured equally horrific devices. The rooms hadn’t been altered since Phnom Penh had been reclaimed, and on the floors and walls, bloodstains were still visible.

So much that we saw that day seemed beyond belief; the fact that most of the Khmer Rouge were children was almost too appalling to contemplate. We were told that the Khmer Rouge soldiers dispatched their victims without remorse and with businesslike efficiency; children killing mothers and fathers and other children by striking them on the back of the head. My oldest son was roughly the same age as the soldiers, which made me sick to my stomach.

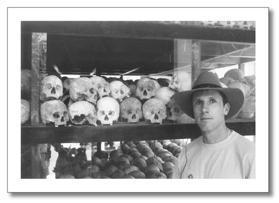

On the walls were pictures of the victims. Some pictures showed prisoners being tortured; others showed the bodies unearthed in the Killing Fields. In either corner of the main room, there were two small temples that housed the skulls of those victims who’d been discovered in the camp after the guards had fled. On the wall was a painting of a young boy in a soldier’s uniform, striking and killing a victim in the Killing Fields. The artist, we learned, had lost his family there.

No one on the tour could think of anything to say. Instead, we moved from sight to sight, shaking our heads and muttering under our breath. Awful. Evil. Sad. Sickening.

More than one member of the tour had to leave; the intensity was overwhelming.

“Did you lose anyone in your family?” I finally asked the guard.

When he answered, he spoke steadily, as if he’d been asked the question a thousand times and could answer by rote. At the same time, he couldn’t hide a quality of what seemed almost stunned disbelief at his own words.

“Yes, I lost almost all of them. My wife, my father, my mother. My grandparents. All my aunts and uncles.”

“Did you have any siblings?”

“Yes,” he said, “a younger brother.”

“Is he still alive?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I haven’t seen him since the war. He was a member of the Khmer Rouge.”

We traveled to the outskirts of Phnom Penh and turned toward the Killing Fields. On either side of the dirt road were run-down houses; halfway up the street was a garment factory, and dozens of women were clustered outside, sitting in the dirt eating lunch as we passed.

Impossible to recognize unless you knew the location, the Killing Fields appeared as a ditch-strewn field, remarkably similar to the rest of the countryside we’d passed. It was far smaller than I imagined it would be—maybe a hundred yards to each side. In the center, the only recognizable feature was a memorial temple to honor the dead.

Over the next hour, we were led from one spot to the next; this was where a hundred victims were discovered; in another spot two hundred victims were found, over here, four hundred. In another spot, we learned that the skeletons unearthed had been buried without their heads, so it was impossible to know how many had been unearthed. In this particular field, we learned that thousands had died; precise figures are impossible to know with any certainty.