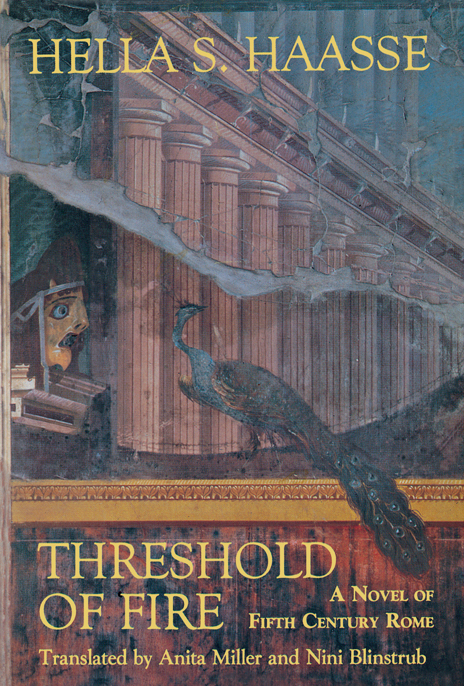

Threshold of Fire

Authors: Hella S. Haasse

Published in 1993 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, IL 60610

Threshold of Fire

Copyright © 1993 Anita Miller

Originally published as

Een Nieuwer Testament

Copyright 1964 © Hella S. Haasse

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges that publication of the book was made possible in part by a grant from the Foundation for the Production and Translation of Dutch Literature.

Printed and bound in the U.S.A. on acid-free paper.

First Edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Haasse, Hella S., 1918—

[Nieuwer testament. English]

Threshold of fire: a novel of fifth century Rome / Hella Haasse;

translated by Anita Miller and Nini Blinstrub. — 1 st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-89733-390-X (acid-free paper)

1. Rome — History — Empire, 30 B.C. 476 A.D. — Fiction. I. Title.

PT5838.H45N513 1993

839.3’1364—dc20 93-2465

CIP

Qui fuerat genitor, natus nunc prosilit idem

Succeditque novus: geminae confinia vitae

Exiguo medius discrimine separat ignis.

Claudius Claudianus:

Phoenix

In this dynamic novel, Hella Haasse illuminates a crucial, yet relatively obscure period of history — roughly 380 to 414 A.D., when Western civilization was undergoing a cataclysmic transformation from late antiquity to the early middle ages. The world was witnessing the death throes of the great Roman Empire — its unity destroyed by a cold war with Constantinople in the East, its military power evaporating before barbarian armies menacing its borders, and its cultural and religious heritage being stamped out by the Church Triumphant. The latter was an astonishing phenomenon: the total obliteration of a traditional religion, the destruction of a way of life.

Although Christianity was legalized in 312, it was under the Emperor Theodosius (346?-395) that it became the official religion of the Roman Empire. Theodosius was baptized in 380, the third year of his reign; he began the process which culminated in the liquidation of paganism and the repression

of heretics. Over fourteen years Theodosius issued a series of edicts: mandating faith in the Trinity, forbidding the use of altars and shrines for purposes of divination, shutting down pagan temples and eventually forbidding, on pain of death, sacrifices to man-made images. These policies were continued, more stringently, by Theodosius’s inept son Honorius.

Theodosius had unquestionably helped to hasten the collapse of the Roman Empire by splitting it in two. On his death in 395, he divided it between Honorius and his elder and equally incompetent son Arcadius, who ruled the Eastern half from his capital in Constantinople. Honorius ruled the West, but it is another indication of impending disintegration that the Emperor no longer resided in Rome: it was too far from the threatened frontiers. He lived in Milan, a precedent that had been established by Constantine; but in 402 Gothic armies under Alaric besieged that city and nearly captured Honorius. So he moved the government to Ravenna, which was set in the midst of marshy tracts and water, and thus protected from invasion. Honorius, as we see in

Threshold of Fire,

rarely made “entry” into Rome.

Theodosius’s sons have been called twilight men ruling in a twilight time. Both relied on regents: Honorius was guided by Flavius Stilicho, a respected Vandal general whose wife, Serena, was Theodosius’s niece and adopted daughter. Arcadius was controlled first by Rufinus, a Gaul of bad reputation, and then by Eutropius, a eunuch who had been a slave. Great hostility developed between East and West. First Rufinus — who was torn to pieces by his own soldiers almost at the feet of Arcadius — and then Eutropius, were bitter enemies of Stilicho.

This is the background against which

Threshold of Fire

is set.

The action of the novel is circular, beginning and ending in July of 414 A.D. (although flashbacks extend its time span to about thirty-five years). We meet first the Prefect Hadrian, a Christian convert and transplanted Egyptian. We meet also Marcus Anicius Rufus, the only member of his devoutly Christian aristocratic family who has chosen to cling to the ancient Roman beliefs and practices. The Prefect heralds the frightening future; Marcus Anicius belongs to the dying past. Two other central figures in the novel are the Jew Eliezar ben

Elijah and the poet Claudius Claudianus.

Eliezar lives according to the tenets of his faith; he is, like Hadrian and Marcus Anicius, a dedicated man and, like them, a tormented one. He has a dark vision of things to come, although he is not for the moment in danger. He is left in peace by the authorities because Jews were assigned a unique place by Theodosius. In 393 their religion was recognized as legal, they were guaranteed right of assembly and their persons and property were officially protected from attack by Christians. But the handwriting was already on the wall: in 388 a synagogue was burned to the ground in Callinicum, a small town on the Persian border, by a fanatical mob led by the local bishop. Theodosius demanded restitution from the bishop on behalf of the Jewish population, but this demand was turned aside by Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, who prevented Theodosius from pursuing the matter.

Ambrose was a man of rigid principles who considered the fight against heresy to be a holy war, and who would give no quarter to Jews or pagans. His threats against Theodosius were the beginning of the subjection of temporal to spiritual power. The most striking example of this

occurred when, on threat of excommunication, Ambrose forced Theodosius to do public penance for the massacre of seven thousand citizens at Thessalonica (now Salonica) in Greece.

It is around the character Claudius Claudianus, known to history as the poet Claudian, that the action flows. Claudian arrived in Italy apparently around 394 and a year or so later became poet to the court of Emperor Honorius. He is generally considered to be the last of the great Latin poets. He wrote panegyrics, invectives and epics, most of them celebrating the accomplishments of his hero and mentor Stilicho. He was a skilful propagandist, but far more than that. He was the master of Latin hexameter poetry under the Late Empire; his influence extended far beyond Italy into the Greek-speaking world. His work was carefully copied out by monks for over a thousand years, and has been invaluable to historians attempting to reconstruct the significant first decade of Honorius’s reign: the tensions and political maneuverings, as well as the battles continually fought against rebels and barbarian chieftains who threatened the decaying sovereignity of Rome.

Claudian was heard from no more after 404.

This was not because he had lost favor with Stilicho, since Stilicho, before he was murdered in 408, arranged for an omnibus edition of Claudian’s works. No one knows what happened to Claudian. It has been suggested that he died, or that he retired to Africa where Stilicho’s wife Serena had arranged a marriage for him with a wealthy widow. But it has been suggested also that he got into trouble because of an epigram he wrote attacking the Prefect Hadrian, contrasting Hadrian’s unsleeping rapacity with the indolent honesty of Mallius Theodorus, consul in 399, for whom Claudian wrote a panegyric, and whom he clearly liked and respected.

Claudian glorified Rome: he saw it as it had been and not as it was. And he saw it through non-Christian eyes. Except for a few ambiguous lines, there is no reference to Christianity in Claudian’s poetry. And although he wrote on mythological themes, he did not necessarily accept the Roman pantheon. It is a reflection of the Prefect’s fanaticism, and possible ignorance, that looking through the book-rolls in Marcus Anicius’s library, he comments with disapproval on “verses teeming with mythological names”; this was the accepted

practice in the poetry of the time, a convention, and not even the bishops complained about it. It should be noted, incidentally, that Marcus Anicius, looking to the past, uses book-rolls at a time when the codex, with its sewn binding, had largely replaced them, thanks to the emphasis placed by Christians upon the Scriptures.

Thus Claudius Claudianus, poet and humanist, stands apart from both the doomed pagan Marcus Anicius, who yearns for a Rome that is lost forever, and the tormented Christian Hadrian, who, like Bishop Ambrose, has spent his life in the Roman civil administration, which was known to breed narrow authoritarianism. Hadrian views the world as Ambrose does, with restricted vision; it is Ambrose and Hadrian who are the wave of the future. Theirs is the state of mind responsible eventually not only for the Inquisition, but for the untold suffering caused by uncompromising political movements in our own century.

Anita Miller

Chicago, Illinois

May, 1993

The novel falls into three parts. The first, “The Prefect”, begins early in the morning on the fifth of July, 414; the second, “Claudius Claudianus”, is set three weeks earlier and the action moves forward to the fourth of July; the third section, called “The Prefect” once again, takes place in the late afternoon and evening of the fifth of July and the morning of the sixth of July.

THE PREFECT