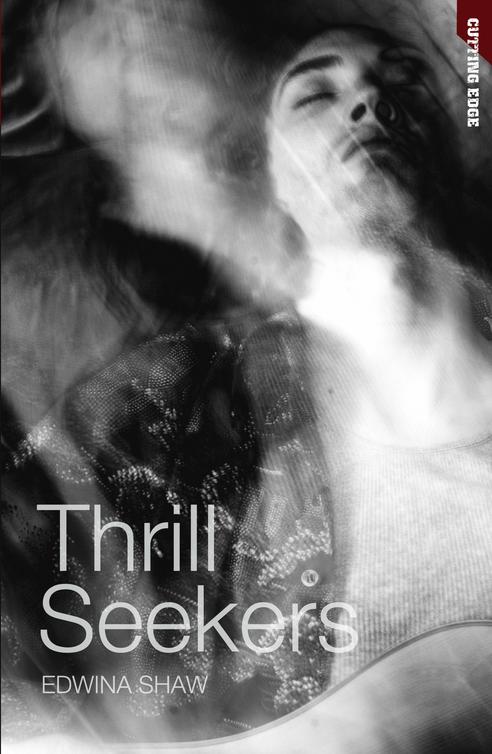

Thrill Seekers

Authors: Edwina Shaw

EDWINA SHAW

In loving memory of my brother Matthew

1967 – 1987

and for all the boys.

I would like to thank the many people whose contributions have made this book possible. Peter Lancett, who saved Thrill Seekers from the scrap heap and helped bring it to its current form, and to Nigel and Jenny at Ransom for not giving up. Helena Pastor and Marion Howes, who know this book almost as well as I do, for their tireless editing, support and friendship. Katherine Howell, Favel Parrett and all my MPHIL and Joondo 8 friends for being a great cheering squad and sympathetic listeners. Veny Armanno, Amanda Lohrey, the late Jan McKemmish, Ben Ball and Barbara Mobbs for their advice and encouragement. My landlords, Romeo and Josephine Ercole, patrons of the arts, whose generosity and cheap rent has enabled me to stay at home and write. My husband Matthias and our children Bonnie and Tom, who gave me the time, space and love that I needed. My old friends, Steven, Marina, Patrick, Kay, Claire, Ivan, Suzi, Lulu and Paul; and my mother Natalie and siblings Natasha, Liam and Paula, who know the truth.

Look. See that box? My dad’s in there, in that box they’re putting into the ground.

I can hear him scratching on the lid.

I want to scream and jump in after the clump of dirt they get me to throw, pull off the lid and rescue him. But my legs won’t move and I stand like an empty tin man as the mud thuds on top of the shiny wood, muffling the sound of his fingernails tearing.

Two weeks ago Dad told us he was dying. Me and my little brother Douggie

sitting there eating breakfast like it was any other day, Vegemite toast turning hard in my throat. Mum sucking the guts out of a cigarette and blowing it out towards the window, not looking at us.

‘I’m not going to get better,’ he said.

‘Oh,’ we said. ‘Oh.’

What did he mean, I wondered. He’d been sick a long time, become skinny and bald and ugly, but people always got better. You got sick, you took your medicine no matter how bad it tasted, and then you were better. That’s how it went.

‘I’m going to die,’ he said, then got up and left us sitting there.

‘Mum?’ I said. ‘It’s not true, is it?’

Douggie didn’t say anything, just sat there with a half-chewed piece of Weetbix still in his open mouth, his eyes big and wide like a possum’s in torchlight.

‘Mum? He’s joking right?’

Mum blew out the last of her smoke and ground the butt into her ashtray. ‘Of course he’s not joking, Brian,’ she sighed. ‘Your father’s sick. Maybe you’d have realised if you weren’t always off playing the fool with your friends on that bloody creek. Don’t you notice anything that’s going on around here? He’s very sick. He’s going to die.’

‘I don’t get it.’

‘What’s there to get? You’re big enough to understand, to start pulling your weight around here.’ She rubbed her forehead. ‘You’re going to have to be the man of the house soon. I can’t do it on my own. I just can’t.’

‘You mean he’s really going to die?’

‘For God’s sake, how plain do I have to make it?’ She gulped the last of her tea. ‘Yes. He’s going to die. D.I.E.’

‘You mean like Fluffy?’ Douggie got it quicker than me. Our guinea pig had been mauled by the neighbour’s red setter last winter and we’d had to bury the bits in a shoebox under the Poinciana tree.

‘Like Fluffy.’ Mum nodded to Douggie with a closed-lip smile.

He started to cry, even though he’s only about a year younger than me, and Mum held him close and patted his hair.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I’m sorry boys. I don’t know what we’re going to do.’ She glanced over like she expected me to cry too.

I didn’t. I’m thirteen, way too big to cry. Anyway I didn’t feel like crying. I was trying to figure it all out. It couldn’t really be true. Guinea pigs, cats, dogs, people on TV, soldiers, they die. Not ordinary people like us. The nuns reckon Jesus died then came back to life again three days later. Old people, they die. Dads don’t.

I couldn’t eat anymore, it all tasted like the box we’d buried Fluffy in. I left Mum and Douggie holding on to each other at the table and went to my room, closed the door and lay on top of my unmade bed listening to the washing machine go round and round and round.

When I couldn’t stand the whirring any longer, I got down on my knees and pointed my fingers to heaven like the nuns had taught me and promised to be good forever if only God would change His mind. I promised I’d never tease Douggie again, or pull his hair or make fun of the stupid way he talks. I’d make my bed and help Mum wash up and never talk back or sneak any more ciggies or money from her purse. I’d do all my homework and not throw rocks from the overpass. I wouldn’t even think about touching girls’ tits. I’d grow up and be a priest. I’d do that and never have any fun ever again, if that would make God change His mind. I made a deal, a bargain to save Dad’s life. It felt like God was listening.

I made my bed straight away, tucked in the corners and folded down the sheet. I put on my school uniform and rubbed the mud off my sneakers with a bit of toilet paper wet with spit, gathered up the clothes from the floor and chucked them in the laundry. God was watching. I wasn’t going to let Dad down.

‘Come on Douggie, stop crying,’ I said as I dragged him down the path to school. ‘It’s going to be all right. I’ve fixed everything.’

My teacher, Sister Bernadette, kept looking at me funny. She must have thought I was about to put pins on her chair again, because she couldn’t seem to understand why I was being so good all of a sudden. At the end of the week she made me wear the best student Holy Medal home. That made Dad smile. But it didn’t make him better.

He stopped going to work, which wasn’t like Dad, and lay in bed all day coughing, with Mum and Gran and strange nurses

fussing over him. When I tried to get him to laugh or play with the ball they said ‘Hush’ and ‘Leave your father in peace’. So I took Douggie out to the backyard instead and we kicked the football to each other in silence. It wasn’t fun anymore. It seemed like nothing was fun.

Every night I prayed hard, made more promises, told God I’d get Douggie to be a priest too if that would help. But as the days wore on and Dad got thinner and greyer and the stink in his room started to turn me away, I knew that God wasn’t listening. Had never been listening. And that even Mother Mary in her long blue gown didn’t see me, there on my knees, by my bed, crying.

The deal was off. I stole half a packet of Mum’s Marlboros and headed down to the creek with my mates. Smoked up a storm.

The sun kept shining like always. I went to school every day and pretended I was normal. But it felt like I wasn’t really me at all. The real me who used to laugh and tease and chase after the girls had disappeared,

gone away camping. He’d left me, some sort of robot double, to keep on doing the stupid things I had to do every day.

It wasn’t me.

On the day before Dad died I went in and sat beside him on the bed, trying not to look at the way his skull showed through the skin on his face and his bald head, the way the tube sticking out of his arm bulged up the skin. Tried to see Dad the way he used to be, before cancer turned him into something scary.

‘Hey,’ he said. His lips were cracked, white pasty stuff was sticking in the corners, and his breath smelled bad.

‘Dad, I …um…’ The words wouldn’t come. I wanted to say, ‘Please don’t die. Don’t go and leave me behind.’ But I couldn’t.

‘Brian, listen to me.’ He coughed and scrunched up his face. I handed him a

tissue from the box on the bedside table that was crammed with pill bottles and a vase of flowers with brown edges and dirty water. ‘You take care of your mother and your brother for me. Okay?’

I nodded.

‘Be a good boy.’ He coughed again and lay back on his pillows with his eyes closed, holding onto his belly.

‘I will.’

He didn’t say any more, just lay there breathing hard and raspy, a deep crease between his eyebrows.

‘I love you Dad,’ I whispered as I rested my head to his bony chest. I lifted his arm and put it, loose and floppy, around my shoulders. But I couldn’t stay there long because of the stink that was coming from under the sheets. It smelt like the dump where we go hunting for treasures. Something rotten.

Mum came in and bustled me out. She didn’t like us kids being in there bothering Dad. She looked almost as skinny as him and was smoking more than ever. I’d even seen her helping him to have a drag on her cigarette, putting the butt up to his crusted lips, brushing them with her fingertips, smoothing back where his hair should have been with her other hand.

The day he died they sent us to school like it was any other day. Pushed us into the bedroom and told us to kiss Dad goodbye. He was still sleeping. I bent down to kiss him on the lips. But they were so awful, so

death-ugly

, that I changed my mind and gave him a quick kiss on the forehead. I should’ve kissed him on the lips. I would have, if I’d known that goodbye was forever.

And so, sometime around lunchtime on Thursday, while I picked at a peanut paste sandwich and pretended to smile at some kid’s stupid joke in the school yard, Dad died. Later, one of my aunties came and picked

me up early from school. I knew as soon as I heard the school gate clanking that it had happened. I tried not to see Aunty Joan, willed it not to be her, even tried praying again, but she got nearer and nearer until she stood at the classroom door with her eyes swollen, twisting a man’s hanky in her hands. She whispered to Sister in the doorway, dark evil figures against the afternoon sun. Sister kept glancing over at me with a frown, nodding and frowning some more.

Her sensible nun shoes tapped to the front of the classroom.

‘Class,’ she said. ‘I have some bad news. Brian’s father has died. He has to go home.’

I wanted to smash her wrinkly old nun face into the floorboards. She told. I hadn’t told anyone, not even my best mate, Jacko. On purpose. I didn’t want any of them to know. Not until I was ready. Till I’d figured it out. Till I could joke about it so they wouldn’t look at me like I was some kind of

freak, which is what they were doing now, their eyes and mouths gaping.

Aunty Joan came over and wrapped her arm around me. I shrugged it off, gathered my stuff and walked out without looking at anyone. I could never go back in there again.

That afternoon the sky turned black just like the bible said it did the day Jesus died. It cracked open with thunder and heavy rain and I stood in the middle of our street until my clothes were soaked, letting the rain hide my tears. Trying to feel real. To get clean again. But I couldn’t clean my insides.

The house was full of aunties and uncles, all talking. There were cakes and biscuits, even some with chocolate, but I wasn’t hungry. I didn’t want treats. I wanted Dad back. And if I couldn’t have that I wanted the house quiet, just me and Mum and Douggie, so I could think. So we could make

a circle together and understand that our number had gone from four to three.

But Mum was surrounded by an army of grown ups who wouldn’t let me near her, who kept pouring booze that smelt like Christmas pudding into her glass, lighting her cigarettes, telling me to shush and let my mother be. No one even noticed I was wet.