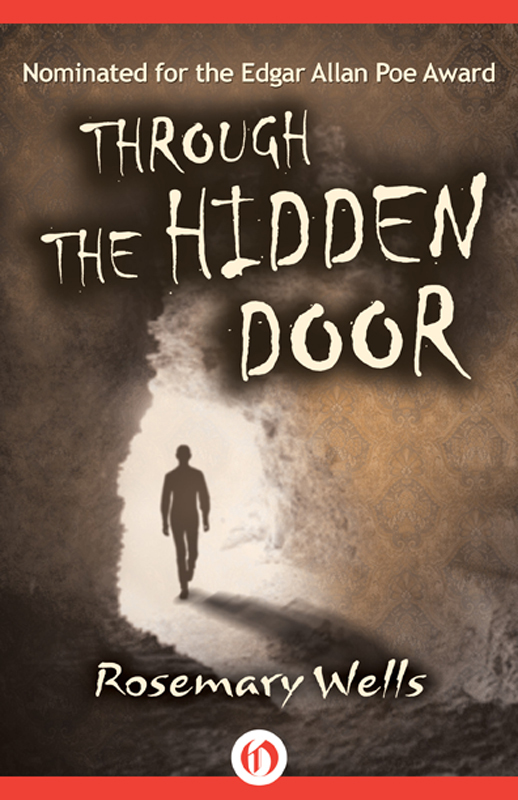

Through the Hidden Door

Read Through the Hidden Door Online

Authors: Rosemary Wells

Rosemary Wells

With drawings by the author

For Ray Phillips

Chapter One

O

N THE DAY OF

the earthquake, just a little after three o’clock, Mr. Finney’s hated collie, Bonnie, scuttled out of a thornbush yowling in pain.

All six of us stopped and looked on. Since the morning earthquake had been only 3.5 on the Richter scale and hadn’t done anything interesting like collapse the school, we had forgotten it by three o’clock. Mr. Finney’s collie, going berserk and bleeding from the mouth, or foot, I couldn’t see which, was something else.

Her silver paws tore at her teeth and scraped against her eyes. Then she began rubbing her jaw up and down furiously against a slender tree, her tongue skidding in and out of her mouth in agony. I stood with the rest of the boys, dumbly. Afraid to do anything because the collie scared the living daylights out of me.

Rudy Sader, quarterback of our football team, forward on the hockey team, and all-state pitcher, threw the first stone. Rudy was a tall, good-looking boy, with brown wavy hair and strange amber-colored eyes. He laughed at the collie. It was a rich and satisfied laugh. I saw the stone hit the animal in the head. The roots of my hair burst into sweat. Danny Damascus threw the next stone.

This one hit the collie on the side of the mouth. The dog looked up at us for a second, not believing. Then she began to cry and shudder, but she stayed there, still cracking her mouth against the bark of the tree.

We hated that collie, as I mentioned before. She belonged to Mr. Finney, headmaster of Winchester Boy’s Academy. We hated Mr. Finney at about the same level as his dog, and we hated his big nosy wife, Dr. Dorothy Finney, who always shot around a corner when you least expected her to, fluttering like some huge kind of poultry. Dr. Dorothy was hard not to bump into. Both Finneys were well liked by most of the boys of Winchester, but my friends and I were not most boys.

The collie had never actually bitten anyone, but the moment you came near her, her lip curled above white teeth, tough as six-penny nails, and she shut her eyes half-mast at you.

“Let’s go, guys! Let’s go!” I pleaded with my friends. Brett MacRea threw a big fat rock. Matthew Hines and Shawn Swoboda began picking up stones. The next one glanced off the white hair on the very top of the collie’s head. Now the dog tried to run away from us, but by this time she had entangled herself, legs and tail, in a grapevine that wound through the thornbush. She lurched, eyes moving wildly, ducking the stones, trying to jerk her body out of the vine, then retching and whining at us piteously, crying for help.

What I did was stand there, in a storm of flying stones and jeering laughter, trying to sound reasonable, almost cheerful, with a trill of panic in my voice. “Come on, guys! We’ll get in trouble. Hey! Stop! We’re going to get in trouble. Come on, we’ll all get Saturday detention!”

Rudy grabbed a dry branch and advanced, doing a little two-step toward the collie. The five boys with me began to yell and laugh and sing curses of all kinds. The dog’s big sable-and-white body, usually splendidly brushed, sagged. “Stop it!” I shouted. “You jerks! You’re going to kill her!”

The vine had worked upward around the dog’s throat. A spray of urine squirted out of her. Her back paws turned lemon yellow where they’d been white.

And all I had the guts to do was stand back with my hands shoved deep in my pockets, shifting from foot to foot, yammering about Saturday detention when the other boys couldn’t even hear me for their own noise and the thrashing, strangling animal pinned in front of them.

That was when Snowy Cobb rocketed out of nowhere and threw himself into the bush, losing his thick glasses, which had gone smashing under him. Snowy ripped the vine from around the collie’s throat and clucked gentle, soothing noises as he untangled the dog, leg by leg.

Our sudden silence danced in the air with the dust.

“Let’s get out of here!” ordered Rudy, and we ran. Oh, did we run. Once I looked over my shoulder. Behind us, rumbling like an elephant through the bushes, clumped Dr. Dorothy Finney, huge-bosomed, and wrapped, as always, in several layers of different tweeds. She matched the late October woods like a camouflaged Jeep. A chain leash jingled in her hand. I didn’t know if Dr. Dorothy saw us. I only prayed Snowy had lost his glasses before he’d had a chance to recognize us.

Alone, I tramped back to the dorm in the cold, covered with the slick sweat of guilt. My friends had gone romping off another way.

I despised my friends. I had since I’d met them. But I’d made no others through the sixth and seventh grades at Winchester. I had skipped lightly and luckily those years. Now my luck had run out, like water skivying down a drain.

When I was eleven years old, I’d been sent to boarding school in the East from Lantry, Colorado, because my mother was long dead and my dad’s work took him all over the world.

Lantry is Nowhere, U.S.A. It is sixty-two miles from Denver. We live there because my dad needs the solitude of the mountains for his peace of mind in between business trips. My dad is a westerner by birth, and he needs the West for its open spaces and mountains, but for as long as I can remember, he has told me, “Train your brain in the East, son, just like I did, and then the world will be your oyster.” Oysters are squidgy, disgusting things, but this is what he means: Go to Winchester. Graduate with honors. Go on to Hotchkiss. Graduate with honors again. Get into Harvard. Magna cum laude from there and on to Yale or Oxford (as he did), and then you will know so much and meet so many well-connected people that you will be able to go out in the world and make lots of money doing whatever it is you love, which, he adds every time he says this, is the only way to live a life.

I have never argued with Dad’s formula because I am too scared of what he says might happen if I veer from The Plan. I might wind up in a nine-to-five job for the rest of my life, taking overcrowded commuter trains, eating a brown-bag lunch at my desk in a cubicle with three other people, and retiring at fifty-five with nothing to show for my life but a gold retirement watch.

So I began my career as an eastern preppy in the sixth grade. With Dad I had traveled to Rangoon, Stockholm, London, and Paris, but never had I been near a rock concert, a sugar maple, or a tollbooth. I didn’t know a Nike from a Ked. I was pudgy and freckled, innocent as a kitten. A mountain boy with a nervous lisp, whose only talent was to draw hardhearted cartoons of my teachers.

On day one at Winchester, Rudy Sader noticed my lisp and nicknamed me Blossom.

The head of the upper form, Mr. Silks, also noticed my lisp. But he hauled me into his office and filled my mouth with selected stones from his fish tank, which he boiled on his office hot plate before every use. With a mouthful of sterile pebbles I recited “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” and all of the entries beginning with the letter

S

in the Boston telephone book for forty minutes a day. By Christmas my lisp was better.

In the second semester Silks changed the diet to marbles, also boiled, and started me on Kipling’s “If” and all the

S

names in the New York City telephone book. The poem “If” contains forty-nine S’s.

In May the lisp vanished, although it surfaced now and then when I got excited. And from May of sixth grade on, no one ever called me Blossom again. Getting a foot into Rudy’s gang came by accident.

During the months I’d spent gargling and mumbling my way from Saccarella to Swydoski, Mr. Silks’s hair looked quite normal to me. I did not realize that the only place hair actually grew on his billiard-ball head was over his ears, or that he cleverly nurtured the hair over his right ear to a length of about eighteen inches. This long and wide flap he layered and combed smoothly over the dome of his head from the right side to the receiving hairs above the left ear, where they were woven in.

Mr. Silks was also our sixth-grade science teacher. One day I had to do an experiment involving two nickels, an ice cube, a rubber band, and a heat source. I chose a blow dryer for the heat source. During the experiment Silks remarked casually that I was a nitwit. I turned to apologize to him, blow dryer full on. The hair flap wafted right off his head. Then it hung horribly, dangling like a skullcap from over his right ear.

Boys fell on the floor, holding their noses and mouths, keening like widows at a wake. Mr. Silks replaced his hair immediately. He had no choice. In a voice like a police siren he ordered me to copy out the Gettysburg address one hundred times.

Rudy and his friends thought I had done this on purpose. I became a minor hero. Mr. Silks was instantly nicknamed Eggnog, school-wide. After that I leapt at every challenge thrown my way. Rudy’s gang accepted me as a comedian and handy brain. From that day in sixth grade on I was a full member. We called ourselves “the guys.” The rest of the boys called us “the untouchables.” We did terrible things.

Through dinner the night of the dog stoning I sat among my happy, untouchable friends. Sweat covered my body like swimmer’s grease. I’d tried showering it away twice. I’d changed my shirt three times, but the guilty dampness spread. The Finneys were nowhere to be seen.

Friday night dinner was always chipped beef on toast. My friends ate as if there were no tomorrow. My stomach shrank to pea size because I was sure there’d be no tomorrow after that afternoon. I began looking around the Great Hall for Snowy Cobb.

I’d never feared anything this much, not even exam proctors, angels of death. I should explain about cheating. In June of my sixth-grade year I found another way of making the gang accept me whole hog. Since then I had prepped Rudy and his friends like a paid tutor for every test and exam, making them lazy and myself indispensable. We did this the night before exams in my room, with me pacing the floor like Hamlet, imitating the teachers’ every tic and affliction.

With a rushing heart I’d led these five class leaders through my class notes. I’d shown them how to shorthand all exam information onto Dr. Scholl’s Air-Pillo insoles in indelible fine-point marker. During an exam they had only to slip off a Top-Sider to access the whole semester’s key jottings like microfilm. This was just one of my seven foolproof cheating systems. Nobody was ever caught.

Danny and Shawn had taken second helpings of chipped beef, which we called chipped barf. Weren’t they even thinking about their future? I prayed that the collie was alive and promised God then and there I’d never help them cheat again. If the collie was dead, I wouldn’t have a snowball’s chance in hell of getting into Hotchkiss, my dad’s alma mater, the following year for high school. Once you go to one “right school,” and Winchester is one of the rightest of schools, getting into the next “right school” is as spine tingling as applying to college.

Rudy Sader would lose his scholarship to Winchester and never make Lawrenceville. He’d wind up back in his hometown high school. This would be death for Rudy’s dream football career. The mothers in Rudy’s hometown were an aggressive bunch who’d bumped football out of his high school’s sports program on the grounds it was dangerous and bred mental illness. There would be no Choate in Danny Damascus’s future. No Taft for Hines or St. Andrew’s and Groton for Shawn and Brett. Cheating at Winchester carried a penalty of instant suspension, or expulsion. Was trying to kill the headmaster’s dog on a level with cheating? I guessed it was worse.

I tried to bury my alarm by shoveling large forkfuls of lukewarm beef into my dehydrated mouth. It stayed right there, curdling. I choked, just like that poor damn collie.