Thunder City (29 page)

He knew that Edith had been changing things in the house. The sounds of heavy furniture scraping the floors had not been heard there since they had moved in, and the conversation of workmen was never conducted in whispers. He assumed the same thing was going on at the Crownover plant. He knew there would be no more opera coaches, no doctors’ buggies, no ladies’ carriages with yellow wheels and pockets for their vanity things; he had said good-bye to it all when his doctors had told him he probably wouldn’t recover even if he agreed to surgery. It was his office that occupied him. They could do what they liked with the desk and the ledgers and the solid, no-nonsense Stickley chairs and sofa, but he hoped they would leave the framed tintype of his father. The image of Abner I’s stunned face, made between the debacle at Harpers Ferry and his miserable death, had behaved as Abner II’s reverse barometer since the day he took over the company. On those rare occasions—rarer, certainly, than they occurred in romantic fiction—when a decision teetered between what was right in general and what was best for Crownover, he’d had only to look at the stricken expression of the man in the photograph to remind him which way to lean. He had never confided that to anyone; he was glad now that he had not. The realization that the surest tool in the company chest might remain available in plain sight, but that none should know its purpose, made him forget momentarily the purgatory in his abdomen.

Abner Crownover II lay absolutely without thinking in his quiet bedroom, hearing the random noises of the house and the nurse’s calloused fingers turning pages and outside the window the harsh expectorant cough of a gasoline-powered automobile making its way up Jefferson.

T

HUNDER

C

ITY COMMEMORATES

the most significant achievement of the twentieth century—America’s transformation, in a few years, from an agricultural nation to the world’s leading industrial power. In that brief span, a method of transportation that had existed relatively unchanged for three thousand years disappeared and was replaced by one that would shrink the globe and blur the lines between rural and town life, small town and city. Not until the computer revolution of the 1980s would another invention appear to lift civilization, Alexander-like, from one groove and place it in another.

It has become fashionable in recent years for certain individuals—among them a vice president of the United States—to decry the invention of the automobile, which they hold to account for destroying the environment and depleting the world’s supply of fossil fuels. (Those most vocal in this belief invariably travel great distances to spread their gospel, apparently on foot.) Few have raised their voices to remind us of the introduction of the decent living wage and the eight-hour day, or the number of lives that have been saved by the gasoline-powered fire engine, police cruiser, and ambulance; numbers that far outweigh those slain in traffic accidents. Every worthwhile development in the history of man has proven itself a Pandora’s box as well as a benevolent djhin, but not since the crossbow has another inspired so much strident rhetoric.

It is the theme of

Thunder City

that the true dark side of the national fantasy, the evolution of organized crime, took place at the same time as the birth of the automobile industry, and that the same combination of vision, determination, and ruthlessness that drove such pioneers as Henry Ford, the Dodge brothers, and Ransom Eli Olds existed in the handful of European immigrants and landed gentry who wedded politics, business, and vice to create what is now undeniably America’s Fifth Estate. Harlan Crownover, James Aloysius Dolan, and Sal Borneo are creations of fancy, but they are by no means fanciful. Their counterparts were genuine and still are.

Other literary devices have been brought to bear in the telling of this story. In the interest of pace and clarity (but not drama, as the case of Henry Ford versus the Selden Trust provides enough for ten books), I have committed certain offenses against historical fact. Chief among these is the compression of time, so that the events of eight years must appear to the casual reader to have taken place within eighteen or so months. Similarly, I have backdated the construction of the Pontchartrain Hotel and its notorious bar a few years to create a consistent gathering place for the Detroit automaking community from the founding of the Ford Motor Company in 1902 to the conquest of the world by the Model T in 1908. The Pontchartrain Club, as the community referred to itself, met there to compare dreams and show off between the building’s dedication in 1907 and 1915, when the members migrated to the Detroit Athletic Club. Sir Walter Scott set the precedent for this type of liberty and I don’t think enough of myself to trumpet a higher standard.

On January 8, 1911, a judge of the New York State Court of Appeals reversed a lower-court ruling to declare the basic technology of the automobile a “social invention” that must be made available to all producers equally. The Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers was immediately disbanded and the industry opened to all comers. Henry Ford, for all the shocking faults of an unstable and bigoted personality, has never received sufficient credit for his valiant one-man stand against the worst threat to free enterprise in this country’s history.

Thunder City

closes the chronicle I have come to call, for want of a better name, the Detroit Series. In these seven books I have attempted to tell the story of America in the twentieth century through the microcosm of Detroit, the one city whose history mirrors precisely the history of the United States of America. These are, in order of chronology rather than date of publication:

Thunder City

(1900–10);

Whiskey River

(1928–1939);

Jitterbug

(1943);

Edsel

(1951–59);

Motown

(1966);

Stress

(1973); and

King of the Corner

(1990). The city since the retirement and death of Coleman Young, its mayor of twenty corrupt years, shows signs as the century turns that it is embarking upon its greatest adventure since the start of the automobile industry, in which case it may warrant at least one more book; but since time is the only guarantor of distance and objectivity, the existing titles in the series must for the time being stand alone.

—Loren D. Estleman

Whitmore Lake, Michigan

January 5, 1999

Loren D. Estleman (b. 1952) is the award-winning author of over sixty-five novels, including mysteries and westerns.

Raised in a Michigan farmhouse constructed in 1867, Estleman submitted his first story for publication at the age of fifteen and accumulated 160 rejection letters over the next eight years. Once

The Oklahoma Punk

was published in 1976, success came quickly, allowing him to quit his day job in 1980 and become a fulltime writer.

Estleman’s most enduring character, Amos Walker, made his first appearance in 1980’s

Motor City Blue

, and the hardboiled Detroit private eye has been featured in twenty novels since. The fifth Amos Walker novel,

Sugartown

, won the Private Eye Writers of America’s Shamus Award for best hardcover novel of 1985. Estleman’s most recent Walker novel is

Infernal Angels

.

Estleman has also won praise for his adventure novels set in the Old West. In 1980,

The High Rocks

was nominated for a National Book Award, and since then Estleman has featured its hero, Deputy U.S. Marshal Page Murdock, in seven more novels, most recently 2010’s

The Book of Murdock

. Estleman has received awards for many of his standalone westerns, receiving recognition for both his attention to historical detail and the elements of suspense that follow from his background as a mystery author.

Journey of the Dead

, a story of the man who murdered Billy the Kid, won a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America, and a Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

In 1993 Estleman married Deborah Morgan, a fellow mystery author. He lives and works in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

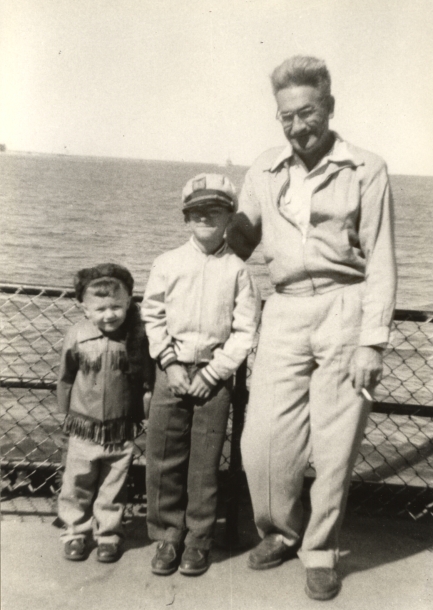

Loren D. Estleman in a Davy Crockett ensemble at age three aboard the Straits of Mackinac ferry with his brother, Charles, and father, Leauvett.

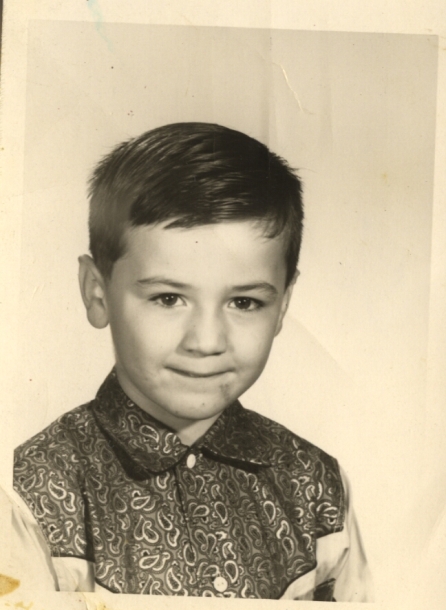

Estleman at age five in his kindergarten photograph. He grew up in Dexter, Michigan.

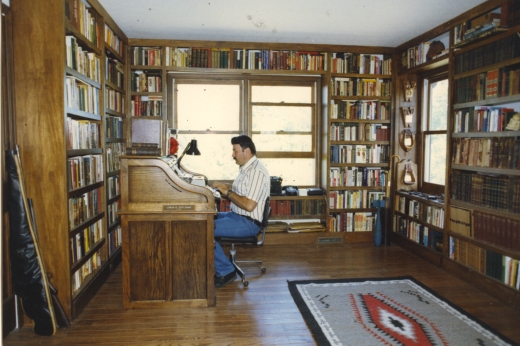

Estleman in his study in Whitmore Lake, Michigan, in the 1980s. The author wrote more than forty books on the manual typewriter he is working on in this image.

Estleman and his family. From left to right: older brother, Charles; mother, Louise; father, Leauvett; and Loren.

Estleman and Deborah Morgan at their wedding in Springdale, Arkansas, on June 19, 1993.

Estleman with actor Barry Corbin at the Western Heritage Awards in Oklahoma City in 1998. The author won Outstanding Western Novel for his book

Journey of the Dead

.