Tigana (23 page)

Authors: Guy Gavriel Kay

P A R T T W O

D I A N O R A

C H A P T E R 7

D

ianora could remember the day she came to the Island.

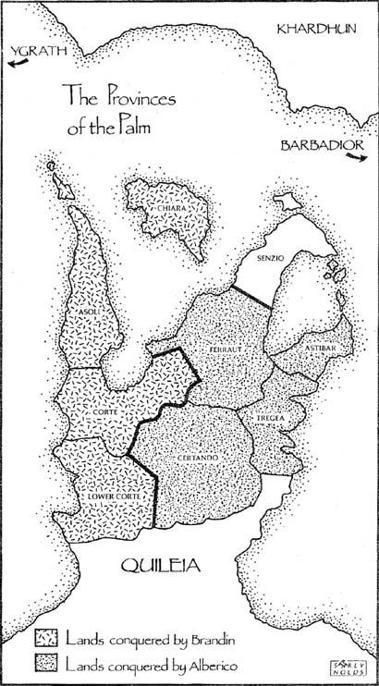

The air that autumn morning had been much like it was today at the beginning of spring—white clouds scudding in a high blue sky as the wind had swept the Tribute Ship through the whitecaps into the harbour of Chiara. Beyond harbour and town the slopes mounting to the hills had been wild with fall colours. The leaves were turning: red and gold and some that clung yet to green, she remembered.

The sails of the Tribute Ship so long ago had been red and gold as well: colours of celebration in Ygrath. She knew that now, she hadn’t known it then. She had stood on the forward deck of the ship to gaze for the first time at the splendour of Chiara’s harbour, at the long pier where the Grand Dukes used to stand to throw a ring into the sea, and from where Letizia had leaped in the first of the Ring Dives to reclaim the ring from the waters and marry her Duke: turning the Dives into the luck and symbol of Chiara’s pride until beautiful Onestra had changed the ending of the story hundreds and hundreds of years ago, and the Ring Dives had ceased. Even so, every child in the Palm knew that legend of the Island. Young girls in each province would play at diving into water for a ring and rising in triumph, with their hair shining wet, to wed a Duke of power and glory.

From near the prow of the Tribute Ship, Dianora had looked up beyond the harbour and palace to gaze at the

majesty of snow-crowned Sangarios rising behind them. The Ygrathen sailors had not disturbed her silence. They had allowed her to come forward to watch the Island approach. Once she’d been safely aboard ship and the ship away to sea they’d been kind to her. Women thought to have a real chance at being chosen for the saishan were always treated well on the Tribute Ships. It could make a captain’s fortune in Brandin’s court if he brought home a hostage who became a favourite of the Tyrant.

Sitting now on the southern balcony of the saishan wing, looking out from behind the ornately crafted screen that hid the women from gawkers in the square below, Dianora watched the banners of Chiara and Ygrath flap in the freshening spring breeze, and she remembered how the wind had blown her hair about her face more than twelve years ago. She remembered looking from the bright sails to the slopes of the tree-clad hills running up to Sangarios, from the blue and white of the sea to the clouds in the blue sky. From the tumult and chaos of life in the harbour to the serene grandeur of the palace just beyond. Birds had been wheeling, crying loudly about the three high masts of the Tribute Ship. The rising sun had been a dazzle of light striking along the sea from the east. So much vibrancy in the world, so rich and fair and shining a morning to be alive.

Twelve years ago, and more. She had been twenty-one years old, and nursing her hatred and her secret like two of Morian’s three snakes twining about her heart.

She had been chosen for the saishan.

The circumstances of her taking had made it very likely, and Brandin’s celebrated grey eyes had widened appraisingly when she was led before him two days later. She’d been wearing a silken, pale-coloured gown, she remembered, chosen to set off her dark hair and the dark brown of her eyes.

She had been certain she would be chosen. She’d felt neither triumph nor fear, even though she’d been pointing her life towards that moment for five full years, even though, in that instant of Brandin’s choosing, walls and screens and corridors closed around her that would define the rest of her days. She’d had her hatred and her secret, and guarding the two of them left no room for anything else.

Or so she’d thought at twenty-one.

For all she’d seen and lived through, even by then, Dianora reflected twelve years later on her balcony, she’d known very little—dangerously little—about a great many things that mattered far too much.

Even out of the wind it was cool here on the balcony. The Ember Days were upon them but the flowers were just beginning in the valleys inland and on the hill slopes, and the true onset of spring was some time off even this far north. It had been different at home, Dianora remembered; sometimes there would still be snow in the southern highlands, when the springtime Ember Days had come and passed.

Without looking backwards, Dianora raised a hand. In a moment the castrate had brought her a steaming mug of Tregean khav. Trade restrictions and tariffs, Brandin was fond of saying in private, had to be handled selectively or life could be too acutely marred. Khav was one of the selected things. Only in the palace of course. Outside the walls they drank the inferior products of Corte or neutral Senzio. Once a group of Senzian khav merchants had come as part of a trade embassy to try to persuade him of improvements in the crop they grew and the cup it brewed.

Neutral, indeed,

Brandin had said judiciously, tasting.

So neutral, it hardly seems to be there

.

The merchants had withdrawn, consternated and pale, desperately seeking to divine the hidden meaning in the Ygrathen Tyrant’s words. Senzians spent much of their time

doing that, Dianora had observed drily to Brandin afterwards. He’d laughed. She’d always been able to amuse him, even in the days when she was too young and inexperienced to do it deliberately.

Which thought reminded her of the young castrate attending her this morning. Scelto was in town collecting her gown for the reception that afternoon; her attendant was one of the newest castrates, sent out from Ygrath to serve the growing saishan in the colony.

He was well trained already. Vencel’s methods might be harsh, but there was no denying that they worked. She decided not to tell the boy that the khav wasn’t strong enough; he would very probably fall to pieces, which would be inconvenient. She’d mention it to Scelto and let him handle the matter. There was no need for Vencel to know: it was useful to have some of the castrates grateful to her as well as afraid. The fear came automatically: a function of who she was here in the saishan. Gratitude or affection she had to work at.

Twelve years and more this spring, she thought again, leaning forward to look down through the screen at the bustling preparations in the square for the arrival of lsolla of Ygrath later that day. At twenty-one she’d been at the peak, she supposed, of whatever beauty she’d been granted. She’d had nothing of such grace at fifteen and sixteen, she remembered—they hadn’t even bothered to hide her from the Ygrathen soldiers at home.

At nineteen she’d begun to be something else entirely, though by then she wasn’t at home and Ygrath was no danger to the residents of Barbadian-ruled Certando. Or not normally, she amended, reminding herself—though this was not, by any means, a thing that really needed a reminder—that she was Dianora di Certando here in the saishan. And across in the west wing as well, in Brandin’s bed.

She was thirty-three years old, and somehow with the years that had slipped away so absurdly fast she was one of the powers of this palace. Which, of course, meant of the Palm. In the saishan only Solores di Corte could be said to vie with her for access to Brandin, and Solores was six years older than she was—one of the first year’s harvest of the Tribute Ships.

Sometimes, even now, it was all a little too much, a little hard to believe. The younger castrates trembled if she even glanced slantwise at them; courtiers—whether from overseas in Ygrath or here in the four western provinces of the Palm—sought her counsel and support in their petitions to Brandin; musicians wrote songs for her; poets declaimed and dedicated verses that spun into hyperbolic raptures about her beauty and her wisdom. The Ygrathens would liken her to the sisters of their god, the Chiarans to the fabled beauty of Onestra before she did the last Ring Dive for Grand Duke Cazal—though the poets always stopped that analogy well before the Dive itself and the tragedies that followed.

After one such adjective-bestrewn effort of Doarde’s she’d suggested to Brandin over a late, private supper that one of the measures of difference between men and women was that power made men attractive, but when a woman had power that merely made it attractive to praise her beauty.

He’d thought about it, leaning back and stroking his neat beard. She’d been aware of having taken a certain risk, but she’d also known him very well by then.

‘Two questions,’ Brandin, Tyrant of the Western Palm, had said, reaching for the hand she’d left on the table. ‘Do you think you have power, my Dianora?’

She’d expected that. ‘Only through you, and for the little time remaining before I grow old and you cease to grant me access to you.’ A small slash at Solores there, but discreet

enough, she judged. ‘But so long as you command me to come to you I will be seen to have power in your court, and poets will say I am more lovely now than I ever was. More lovely than the diadem of stars that crowns the crescent of the girdled world … or whatever the line was.’

‘

The curving diadem,

I think he wrote.’ He smiled. She’d expected a compliment then, for he was generous with those. His grey eyes had remained sober though, and direct. He said, ‘My second question: Would I be attractive to you without the power that I wield?’

And that, she remembered, had almost caught her out. It was too unexpected a question, and far too near to the place where her twin snakes yet lived, however dormant they might be.

She’d lowered her eyelashes to where their hands were twined.

Like the snakes,

she thought. She backed away quickly from that thought. Looking up, with the sly, sidelong glance she knew he loved, Dianora had said, feigning surprise: ‘Do you wield power here? I hadn’t noticed.’

A second later his rich, life-giving laughter had burst forth. The guards outside would hear it, she knew. And they would talk. Everyone in Chiara talked; the Island fed itself on gossip and rumour. There would be another tale after tonight. Nothing new, only a reaffirmation in that shouted laughter of how much pleasure Brandin of Ygrath took in his dark Dianora.

He’d carried her to the bed then, still amused, making her smile and then laugh herself at his mood. He’d taken his pleasure, slowly and in the myriad of ways he’d taught her through the years, for in Ygrath they were versed in such things and he was—then and now—the King of Ygrath, over and above everything else he was.

And she? On her balcony now in the springtime morning sunlight Dianora closed her eyes on the memory of how that

night, and before that night—for years and years before that night—and after, after even until now, her own rebel body and heart and mind, traitors together to her soul, had slaked so desperate and deep a need in him.

In Brandin of Ygrath. Whom she had come here to kill twelve years ago, twin snakes around the wreckage of her heart, for having done what he had done to Tigana which was her home.

Or had been her home until he had battered and levelled and burned it and killed a generation and taken away the very sound of its name. Of her own true name.

She was Dianora di Tigana bren Saevar and her father had died at Second Deisa, with an awkwardly handled sword and not a sculptor’s chisel in his hand. Her mother’s spirit had snapped like a water reed in the brutality of the occupation that followed, and her brother, whose eyes and hair were exactly like her own, whom she had loved more than her life, had been driven into exile in the wideness of the world. He’d been fifteen years old.

She had no idea where he was all these years after. If he was alive, or dead, or far from this peninsula where tyrants ruled over broken provinces that had once been so proud. Where the name of the proudest of them all was gone from the memory of men.

Because of Brandin. In whose arms she had lain so many nights through the years with such an ache of need, such an arching of desire, every time he summoned her to him. Whose voice was knowledge and wit and grace to her, water in the dryness of her days. Whose laughter when he set it free, when she could draw it forth from him, was like the healing sun slicing out of clouds. Whose grey eyes were the troubling, unreadable colour of the sea under the first cold slanting light of morning in spring or fall.

In the oldest of all the stories told in Tigana it was from the grey sea at dawn that Adaon the god had risen and come to Micaela and lain with her on the long, dark, destined curving of the sand. Dianora knew that story as well as she knew her name. Her true name.

She also knew two other things at least as well: that her brother or her father would kill her with their hands if either were alive to see what she had become. And that she would accept that ending and know it was deserved.

Her father was dead. Her heart would scald her at the very thought of her brother so, even if death might spare him a grief so final as seeing where she had come, but each and every morning she prayed to the Triad, especially to Adaon of the Waves, that he was overseas and so far away from where tidings might ever reach him of a Dianora with dark eyes like his own in the saishan of the Tyrant.