Tigana (76 page)

Authors: Guy Gavriel Kay

‘My lord,’ he said softly to the old man sitting there with him, ‘do you know that I have come to love you in the time we have been together?’

‘By the Triad!’ Sandre said, a little too quickly. ‘And I haven’t even given you the potion!’

Baerd smiled, said nothing, able to guess at the bindings the old Duke must have within himself. A moment later though, he heard Sandre murmur, in a very different voice:

‘And I you, my friend. All of you. You have given me a second life and a reason for living it. Even a hope that

a future worth knowing might lie ahead of us. For that you have my love until I die.’

Gravely, he held out a palm and the two of them touched fingers in the darkness. They were sitting thus, motionless, when they heard the sound of an oar splash gently in the water. Both men rose silently, reaching for their swords. Then they heard an owl hoot from the river.

Baerd called softly back, and a moment later a small boat bumped gently against the sloping bank and Catriana, stepping lightly, came ashore.

At the sight of her Baerd drew a breath of pure relief; he had been more afraid for her than he could ever have said. There was a man behind her in the boat holding the oars but the moons had not yet risen and Baerd couldn’t see who it was.

Catriana said, ‘That was quite a blow. Should I be flattered?’

Sandre, behind him, chuckled. Baerd felt as though his heart would overflow with pride in this woman, in the calm, matter-of-factness of her courage. Matching her tone with an effort he said only, ‘You shouldn’t have shrieked. Half of Tregea thought you were being ravished.’

‘Yes, well,’ she said drily. ‘Do forgive me. I wasn’t sure myself.’

‘What happened to your hair?’ Sandre asked suddenly from behind, and Baerd, moving sideways, saw that it had indeed been cropped away, in a ragged line above her shoulders.

She shrugged, with exaggerated indifference. ‘It was in the way. We decided to cut it off.’

‘Who is

we?

’ Baerd asked. Something within him was grieving for her, for the assumed casualness of her manner. ‘Who is in the boat? I assume a friend, given where we are.’

‘A fair assumption,’ the man in the boat answered for himself. ‘Though I must say I could have picked a better place for our contraina to have a business meeting.’

‘Rovigo!’

Baerd murmured, with astonishment and a swift surge of delight. ‘Well met! It has been too long.’

‘Rovigo d’Astibar?’ Sandre said suddenly, coming forward. ‘Is that who this is?’

‘I

thought

I knew that voice,’ Rovigo said, shipping his oars and standing up abruptly. Baerd moved quickly down to the bank to steady the boat. Rovigo took two precise strides and leaped past him to the shore. ‘I do know it, but I cannot believe I am hearing it. In the name of Morian of Portals, have you come back from the dead, my lord?’

Even as he spoke he knelt in the tall grass before Sandre, Duke of Astibar. East of them, beyond where the river found the sea, Ilarion rose, sending her blue light along the water and over the waving grasses of the bank.

‘In a manner of speaking I have,’ Sandre said. ‘With my skin somewhat altered by Baerd’s craft.’ He reached down and pulled Rovigo to his feet. The two men looked at each other.

‘Alessan wouldn’t tell me last fall, but he said I would be pleased when I learned who my other partner was,’ Rovigo whispered, visibly moved. ‘He spoke more truly than he could have known. How is this possible, my lord?’

‘I never died,’ Sandre said simply. ‘It was a deception. Part of a poor, foolish old man’s scheme. If Alessan and Baerd had not returned to the lodge that night I would have killed myself after the Barbadians came and went.’ He paused. ‘Which means, I suppose, that I have you to thank for my present state, neighbour Rovigo. For various nights through the years outside my windows. Listening to the spinning of our feeble plots.’

Under the slanting blue moonlight, there was a certain glint in his eye. Rovigo stepped back a little, but his head was high and he did not avert his gaze. ‘It was in a cause that you now know, my lord.’ he said. ‘A cause you have joined.

I would have cut out my tongue before betraying you to Barbadior. I think you must know that.’

‘I do know that,’ Sandre said after a moment. ‘Which is a great deal more than I can say for my own kin.’

‘Only one of them,’ Rovigo said quickly, ‘and he is dead.’

‘He is dead,’ Sandre repeated. ‘They are all dead. I am the last of the Sandreni. And what shall we do about it, Rovigo? What shall we do with Alberico of Barbadior?’

Rovigo said nothing. It was Baerd who answered, from the water’s edge.

‘Destroy him,’ he said. ‘Destroy them both.’

P A R T F I V E

T H E M E M O R Y O F A F L A M E

C H A P T E R 1 7

S

celto woke her very early on the morning of the ritual. She had spent the night alone, as was proper, and had made offerings the evening before at the temples of Adaon and Morian both. Brandin was careful now to be seen observing all rites and proprieties of the Palm. In the temples the priests and the priestesses had been almost fawning in their solicitude. In what she was doing there was power for them and they knew it.

She’d had a short and restless sleep and when Scelto touched her awake, gently, and with a mug of khav already to hand, she felt her last dream of the night slipping away from her. Closing her eyes, only half conscious, she tried to chase it, sensing the dream receding as if down corridors of her mind. She pursued, trying to reclaim an image that would hold it, and then, just as it seemed about to fade and be lost, she remembered.

She sat up slowly in bed and reached for the khav, cradling it in both hands, seeking warmth. Not that the room was cold, but she had now remembered what day it was, and there was a chill in her heart that went beyond foreboding and touched certainty.

When Dianora had been a very small girl—perhaps five years old, a little less than that—she had had a dream of drowning one night. Sea waters closing over her head, and a vision of something dark, a shape, final and terrible,

approaching to draw her down into lightless depths.

She had come awake gasping and screaming, thrashing about in bed, uncertain of where she even was.

And then her mother had been there, holding Dianora to her heart, murmuring, rocking her back and forth until the frantic sobbing ceased. When Dianora had finally lifted her head from her mother’s breast, she had seen by candlelight that her father was there as well, holding Baerd in his arms in the doorway. Her little brother had been crying too, she saw, shocked awake in his own room across the hall by her screams.

Her father had smiled and carried Baerd over to her, and the four of them had sat there in the middle of the night on Dianora’s bed while the candles cast light in circles around them, shaping an island in the dark.

‘Tell me about it,’ she remembered her father saying. Afterwards he had made shadow figures for them with his hands on the wall and Baerd, soothed and drowsy, had fallen asleep again in his lap. ‘Tell me the dream, love.’

Tell me the dream, love

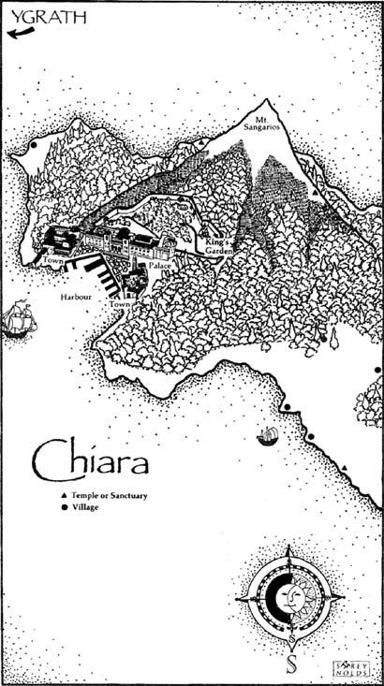

. On Chiara, almost thirty years after, Dianora felt an ache of loss, as if it had all been but a little while ago. Days, weeks, no time at all. When had those candles in her room lost their power to hold back the dark?

She had told her mother and father, softly so as not to wake Baerd, some of the fear coming back in the stumbling words. The waters closing over her, a shape in the depths drawing her down. She remembered her mother making the sign against evil, to unbind the truth of the dream and deflect it away.

The next morning, before opening his studio and beginning his day’s work, Saevar had taken both his children past the harbour and the palace gates and south along the beach, and he had begun to teach them to swim in a shallow cove sheltered from the waves and the west wind. Dianora had expected to be afraid when she realized where they were

going, but she was never really afraid of anything when her father was with her, and she and Baerd had both discovered, with whoops of delight, that they loved the water.

She remembered—so strange, the things one remembered—that Baerd, bending over in the shallows that first morning, had caught a small darting fish between his hands, and had looked up, eyes and mouth comically round with surprise at his own achievement, and their father had shouted with laughter and pride.

Every fine morning that summer the three of them had gone to their cove to swim and by the time autumn came with its chill and then the rains Dianora felt as easy in the water as if it were a second skin to her.

Once, she remembered—and there was no surprise to this memory lingering—the Prince himself had joined them as they walked past the palace. Dismissing his retinue, Valentin strolled with the three of them to the cove and disrobed to plunge into the sea beside their father. Straight out into the waves he had gone, long after Saevar stopped, past the sheltering headland of the cove and into the choppy whitecaps of the sea. Then he had turned around and come back to them, his smile bright as a god’s, his body hard and lean, droplets of water sparkling in his golden beard.

He was a better swimmer than her father was, Dianora could see that right away, even as a child. She also knew, somehow, that it really didn’t matter. He was the Prince, he was

supposed

to be better at everything.

Her father remained the most wonderful man in the world, and nothing she could imagine learning was ever going to change that.

Nothing ever had, she thought, shaking her head slowly in the saishan, as if to draw free of the clinging, spidery webs of memory. Nothing ever had. Though Brandin, in another, better world, in his imaginary Finavir, perhaps …

She rubbed her eyes and then shook her head again, still struggling to come awake. She wondered suddenly if the two of them, her father and the King of Ygrath, had seen each other, had actually looked each other in the eye that terrible day by the Deisa.

Which was such a hurtful thought that she was afraid that she might begin to cry. Which would not do. Not today. No one, not even Scelto—especially not Scelto, who knew her too well—must be allowed to see anything in her for the next few hours but quiet pride, and a certainty of success.

The next few hours. The last few hours.

The hours that would lead her to the margin of the sea and then down into the dark green waters which were the vision of the riselka’s pool. Lead her to where her path came clear at last and then came, not before time, and not without a certain relief beneath the fear and all the loss, to an end.

It had unfolded with such direct simplicity, from the moment she had stood by the pool in the King’s Garden and seen an image of herself amid throngs of people in the harbour, and then alone underwater, drawn towards a shape in darkness that was no longer a source of childhood terror but, finally, of release.

That same day, in the library, Brandin had told her he was abdicating in Ygrath in favour of Girald, but that Dorotea his wife was going to have to die for what she had done. He lived his life in the eyes of the world, he said. Even had he wished to spare her, he would have no real choice.

He didn’t wish to spare her, Brandin said.

Then he spoke of what else had come to him on his ride that morning through the pre-dawn mists of the Island: a vision of the Kingdom of the Western Palm. He was going to make that vision real, he said. For the sake of Ygrath itself, and for the people here in his provinces. And for his own soul. And for her.

Only those Ygrathens willing to become people of his four joined provinces would be allowed to stay, he said; all others were free to sail home to Girald.

He would remain. Not just for Stevan and the response shaped in his heart to his son’s death, though that would hold, that was constant, but to build a united realm here, a better world than he had known.

That would hold, that was constant

.

Dianora had listened to him, had felt her tears beginning to fall, and had moved to lay her head in his lap beside the fire. Brandin held her, moving his hands through her dark hair.

He would need a Queen, he had said.

In a voice she had never heard before; one she had dreamt of for so long. He wanted to have sons and daughters here in the Palm now, Brandin said. To start again and build upon the pain of Stevan’s loss, that something bright and fair might emerge from all the years of sorrow.

And then he spoke of love. Drawing his hands gently through her hair he spoke of loving her. Of how that truth had finally come home into his heart. Once, she would have thought it far more likely that she might grasp and hold the moons than ever hear him speak such words to her.

She wept, unable to stop, for in his words it was all gathering now, she could see how it was coming together, and such clarity and prescience was too much for a mortal soul. For her mortal soul. This was the Triad’s wine, and there was too much bitter sorrow at the bottom of the cup. She had seen the riselka, though, she

knew

what was coming, where the path would lead them now. For one moment, a handful of heartbeats, she wondered what would have happened had he whispered these same words to her the night before instead of leaving her alone with the fires of memory. And that thought hurt as much as anything ever had in all her life.