Time Travel: A History (11 page)

Read Time Travel: A History Online

Authors: James Gleick

Tags: #Literary Criticism, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science, #History, #Time

He feels the existence of two parallel worlds, seventeen years apart yet existing simultaneously. Worse, after these “mysterious leaps and turns through time,” why should there be only two?

Now I accepted the nightmare of an infinity of universes, in which the official time represented only the relative displacement of my consciousness from one to another, and then on to another.

Now— and now— and then another now.

Three o’clock—I am aware of the world in which I feature holding a pen. Three o’clock and one second—I am aware of the next universe in which I feature putting down my pen, etc.

It’s too much for the human mind to comprehend; mercifully, his memories begin to fade, as all memories do. What he has written of the past—the future, and then the past—begins to seem like a dream. “Only once in a while, more and more infrequently, do I have the very ordinary sensation of déjà vu.”

What is memory, for a time traveler? A conundrum. We say that memory “takes us back.” Virginia Woolf called memory a seamstress “and a capricious one at that.” (“Memory runs her needle in and out, up and down, hither and thither. We know not what comes next, or what follows after.”)

“I can’t remember things before they happen,” says Alice, and the Queen retorts, “It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.” Memory both is and is not our past. It is not recorded, as we sometimes imagine; it is made, and continually remade. If the time traveler meets herself, who remembers what, and when?

In the twenty-first century the paradoxes of memory grow more familiar. Steven Wright remarks: “Right now I’m having amnesia and déjà vu at the same time. I think I’ve forgotten this before.”

*1

Rosalind adds: “I’ll tell you who time ambles withal, who time trots withal, who time gallops withal, and who he stands still withal.”

*2

The philosopher and physicist Ernst Mach, a forebear of relativity, objected to absolute time in 1883: “It is utterly beyond our power to measure the changes of things by time….Time is an abstraction at which we arrive by means of the changes of things.” Einstein quoted that approvingly when he wrote Mach’s obituary in 1916, but he himself could not go so far in expunging the convenient abstraction. Time remained an essential property of his universe.

*3

Time travel by circumnavigation? Poe seems to have been the first to make literary use of the possibility, in 1841 (“A Succession of Sundays,”

Saturday Evening Post

), before Jules Verne made it the surprise ending of

Around the World in Eighty Days.

*4

The same thought came as a revelation to Israel Zangwill when he reviewed

The Time Machine

in 1895: “The star whose light reaches us to-night may have perished and become extinct a thousand years ago, the rays of light from it having so many millions of miles to travel that they have only just impinged upon our planet. Could we perceive clearly the incidents on its surface, we should be beholding the Past in the Present, and we could travel to any given year by travelling actually through space to the point at which the rays of that year would first strike upon our consciousness. In like manner the whole Past of the earth is still playing itself out—to an eye conceived as stationed to-day in space, and moving now forwards to catch the Middle Ages, now backwards to watch Nero fiddling over the burning of Rome.”

*5

Wien was the inventor of the

Löschfunkensender,

an early radio transmitter used, for example, on the

Titanic.

*6

Peter Galison, an authority on this matter, suggests that Einstein and Besso, conversing on that fateful day in May 1905, must have been standing on a hill in northeast Bern, where they could simultaneously see both Bern’s old clock tower and another to the north, in the town of Muri.

FIVE

By Your Bootstraps

I don’t want to talk about time travel shit, because we’ll start talking about it and then we’ll be here all day talking about it and making diagrams with straws.

—Rian Johnson (2012)

A MAN SITS

in a locked room with his cigarettes, pots of coffee, and a typewriter. He knows all about time. He even knows about time travel. He is Bob Wilson, a Ph.D. candidate struggling to complete his thesis, “An Investigation into Certain Mathematical Aspects of a Rigor of Metaphysics.” Case in point: “the concept ‘Time Travel.’ ” He types, “Time travel may be imagined and its necessities may be formulated under any and all theories of time, formulae which resolve the paradoxes of each theory.” More quasiphilosophical handwaving. “Duration is an attribute of consciousness and not of the plenum. It has no

Ding an Sich.

”

Behind him he hears a voice. “Don’t bother with it,” the voice says. “It’s a lot of utter hogwash anyway.” Bob turns to see “a chap about the same size as himself and much the same age”—or maybe just a bit older, with a three-day beard and a black eye and a swollen upper lip. The chap has apparently emerged from a hole hanging in the air: “a great disk of nothing, of the color one sees when the eyes are shut tight.” He opens a cupboard, finds the bottle, and helps himself to Bob’s gin. He looks vaguely familiar and he certainly knows his way around. “Just call me Joe,” he says.

We see where this is going—we, people of the future, the time-savvy twenty-first century—but this story is taking place in 1941, and poor Bob is slow to catch on.

Bob’s visitor explains that the hole in the air is a Time Gate. “Time flows along side by side on each side of the Gate….You can walk into the future just by stepping through that circle.” Joe wants Bob to walk through the Gate into the future. Bob doubts whether this is a good idea. As they discuss it, passing the gin bottle back and forth, a third man materializes. He bears a certain family resemblance to Bob and Joe. He does

not

want Bob to enter the gate. Now it’s a committee. The phone rings: a fourth man, checking on everyone’s progress.

Speculative philosophers and pulp readers had predicted this. In time travel, you can meet yourself. It’s finally happening, and it’s happening every which way. Before we are done we will have five protagonists, and they are all Bob. The author was Bob, too: Robert Anson Heinlein, writing under one of his several pen names, Anson MacDonald. His original title was “Bob’s Busy Day”; the pulp magazine

Astounding Science Fiction

published it in October 1941 as “By His Bootstraps.” It was the most intricate, complex, carefully plotted exercise in time travel to date.

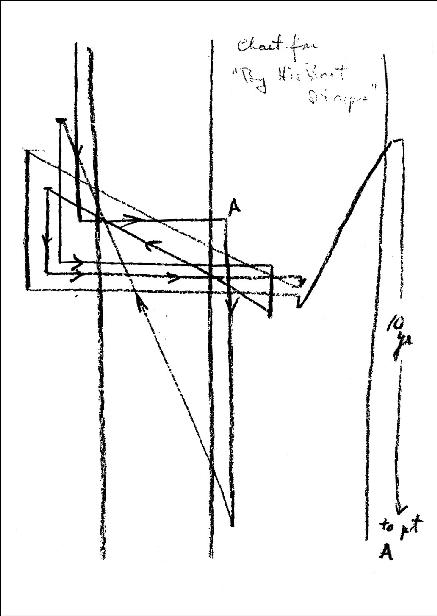

No grandfathers die, no future mothers are impregnated, but wisecracks are exchanged and punches thrown. Scenes are narrated by one Bob and then reprised from the point of view of an older, more knowing Bob. You might expect “Joe” to remember his first encounter with Bob, but he finds the changed perspective confusing. Recognition only dawns slowly. The Bobs have to climb a ladder of growing self-awareness. To unravel the timeline we need a Minkowskiish diagram. Heinlein drew one for himself while drafting the story.

Really, of course, there are multiple timelines in play. Besides the Bobs’, there is the reader’s: the arc of the narrative. Our point of view is the one that matters. The author coaxes us gently along. He says of his poor hero, “He knew that he had about as much chance of understanding such problems as a collie has of understanding how dog food gets into cans.”

Robert Heinlein came from Butler, Missouri, in the heart of the Bible Belt, and made his way to Southern California by way of the U.S. Navy, in which he served between the wars as a midshipman and sometime radio officer aboard the

Lexington,

one of the first aircraft carriers. He considered himself well skilled in ordnance and fire control, but after a collapse from pneumonia he was discharged as disabled. He wrote his first story in 1939 for a contest.

Astounding Science Fiction

paid him seventy dollars for it, and he began pounding the typewriter; he quickly became one of the pulps’ most prolific and original writers. “By His Bootstraps” was one of more than twenty stories and short novels he published under various names in the next two years alone.

That first prizewinning story, “Life-Line,” began in a familiar way: a mysterious man of science explains to a group of skeptical listeners that time is, still and always, the fourth dimension. “Maybe you believe it, perhaps not,” he says. “It has been said so many times that it has ceased to have any meaning. It is simply a cliché that windbags use to impress fools.” He asks them now to take it literally and to visualize the shape of a human being in four-dimensional spacetime. What is a human being? A spacetime entity measurable on four axes.

In time, there stretches behind you more of this space-time event, reaching to, perhaps, 1905, of which we see a cross section here at right angles to the time axis, and as thick as the present. At the far end is a baby, smelling of sour milk and drooling its breakfast on its bib. At the other end lies, perhaps, an old man some place in the 1980s. Imagine this space-time event…as a long pink worm, continuous through the years.

A long pink worm. Slowly and gingerly, the culture was digesting the space-time continuum. The easy bits no longer needed quite so much explaining, so some nuances could be revealed.

The fun of “By His Bootstraps” lies in the comic encounters of the Bobs; it’s a one-man farce times five, with misplaced hats, a confused and irate girlfriend (the word

two-timing

has never been so apt), and, with the Time Gate, the sci-fi equivalent of comically timed slamming doors. The hat is tossed and found and lost again until it seems to be multiplying like rabbits. Bob gets drunk with Bob. Bob recoils at the sight of drunken Bob, and Bob calls Bob some choice names. But Heinlein also takes some pains with the science. Or the philosophy. The eldest and wisest of the Bobs, living thirty thousand years in the future, tells one of his past selves, “Causation in a plenum need not be and is not limited by a man’s perception of duration.” Young Bob thinks about this and offers a comeback: “Just a second. How about entropy? You can’t get around entropy.” And so on. Examined closely, this gab is as hollow as the painted storefronts on the set of a Western.

Heinlein himself apparently didn’t think much of the story at first and was surprised when the magazine’s influential editor, John W. Campbell, assured him it was something special. In its way, it begins to grapple with two philosophical difficulties that arise when people start looping back through spacetime. One is the problem of who they are—the continuity of the self, let’s call it. It’s all well and good to talk about Bob Number One and Bob Number Two and so on, but the diligent narrator finds language ill equipped to keep everyone sorted: “His earlier self faced him, pointedly ignoring the presence of the third copy.” Suddenly English doesn’t have enough pronouns.

His memory had not prepared him for who the third party would turn out to be.

He opened his eyes to find that his other self, the drunk one, was addressing the latest edition.

Not only does Bob gaze upon himself—worse, he doesn’t like the way he looks: “Wilson decided he did not like the chap’s face.” (But we don’t need time travel to reproduce that experience. We have mirrors.)

What is the self? A question for the twentieth century to ponder, from Freud to Hofstadter and Dennett with detours through Lacan, and time travel provides some of the more profound variations on the theme. We have split personalities and alter egos galore. We have learned to doubt whether we

are

our younger selves, whether we will be

the same person

when we next look. The literature of time travel (though Bob Heinlein, in 1941, would not have dreamt of calling his work literature)

*1

begins to offer a way into questions that might otherwise belong to philosophers. It looks at them viscerally and naïvely—as it were, nakedly.

If you’re having a conversation with someone, can that person be you? When you reach out and touch someone, is it a different person, by definition? Can you have

memories

of a conversation while you’re speaking the very words?

Wilson’s head started to ache again. “Don’t do that,” he pleaded. “Don’t refer to that guy as if he were me.

This is me,

standing here.”

“Have it your own way. That is the man you

were.

You remember the things that are about to happen to him, don’t you?”