Titanic (12 page)

Authors: Deborah Hopkinson

Captain E. J. Smith returned to the bridge of his brand-new ship. He gave orders for the lifeboats to be readied.

Fourth Officer Boxhall had a question for him: “‘Is it really serious?’”

“‘Mr. Andrews tells me he gives her from an hour to an hour and a half’” came the reply.

If Andrews was correct, the crew would have only sixty to ninety minutes to uncover, load, and launch the lifeboats — lifeboats that had room for only 1,178 at the most.

The

Titanic

needed help.

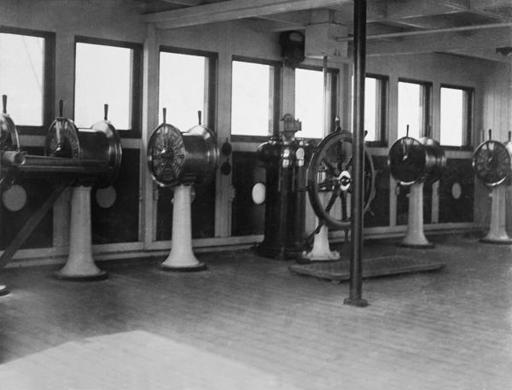

(Preceding image)

Although this is the Wheelhouse from the

Titanic

’s sister ship, the

Olympic

, the two were nearly identical.

The

Titanic

was supposed to be practically unsinkable because she was designed with special features to protect the ship from leaks. The bottom of the ship was broken into sixteen main compartments, separated by walls or partitions called “bulkheads.” These bulkheads had special watertight doors. In an emergency, the doors could be lowered from the bridge to seal off each area and prevent water from spreading into other areas of the ship. And that’s exactly what First Officer Murdoch did as the

Titanic

approached the iceberg.

So why didn’t the

Titanic

’s watertight doors keep the ship from sinking?

First, the damage from the iceberg was simply too spread out. The

Titanic

would probably have stayed afloat with any two of her most forward five bulkhead compartments flooded. It could even have floated if three of the first five leaked. (See the British Wreck Commissioner’s final report on the flooding on page 246.) But the iceberg caused leaks in the first six compartments along the starboard side.

Researcher David G. Brown and others note that the initial flooding of the first three holds and Boiler Rooms 6 and 5 came in through the bottom of the ship, not over the tops of the bulkheads. These primary areas filled up from below, as did Boiler Room 4. However, eventually secondary flooding occurred, as water poured down over the tops of the bulkheads once the ship’s bow began to sink.

The watertight doors helped seal off the compartments from one another, but the tops of the partitions themselves were not sealed off. The bulkheads only went up vertically as high as E Deck. So, as the bow of the ship began to sink, water did begin to overflow the

tops

of the bulkheads, causing enormous stress on the hull. “The downward tipping of the bow created tremendous strain or stress within the hull because the stern was lifted out of the water,” notes Brown.

In other words, as the first compartments filled from below, the weight of the water pulled the ship down. The bow sank lower. Later, water spilled over the top of the bulkheads and down into the compartments behind them. Because there was no way to seal off the top of each separate area, the water brought the ship lower minute by minute. There was no way for the ship to recover.

Titanic

researcher David G. Brown argues that the ship might have had a chance to stay afloat longer by using her pumps — if Captain Smith had not ordered the engines to start again, causing Boiler Room 6 to flood even more.

Brown puts it this way: “Ironically,

Titanic

sank because water poured down from above, not up through the bottom.”

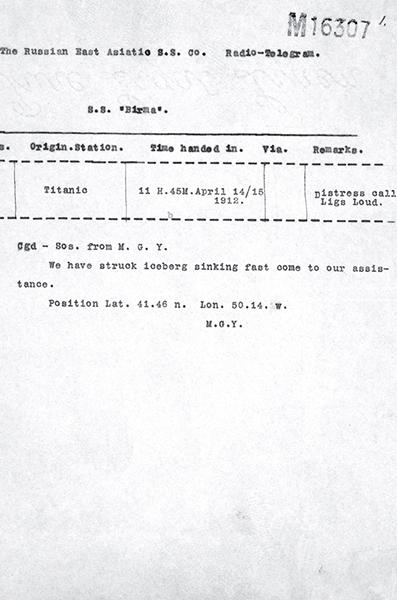

(Preceding image)

A distress telegram from the

Titanic

, which was sent by wireless operator Jack Phillips to the Russian Steamer SS

Birma

, shortly before the

Titanic

sank.

“Captain Smith . . . appeared nervous. He came down on deck, chewing a toothpick. ‘Let everyone,’ he said, ‘put on a lifebelt. It is more prudent.’”

— Pierre Maréchal, first class passenger

Joseph Boxhall hadn’t stopped since the collision. Captain Smith had sent him here and there — to do a brief inspection, to find the ship’s carpenter, to fetch other officers who were off duty for an “all hands on deck.”

Before the captain left the bridge to talk to the chief engineer, he’d given Boxhall yet another job: to update the ship’s position and bring it to the Marconi room so the radio operators could let other ships know where they were.

Using his estimate of the ship’s speed, as well as her course and observations of the stars, Boxhall jotted down the coordinates as best as he could figure them — lat 41°46’ N, long 50°14’ W.

In 1985, the

Titanic

wreck was discovered about thirteen miles south and east of Joseph Boxhall’s coordinates. The wreck’s position is lat 41°43’ N, long 49°56’ W. Even with the ship drifting perhaps two miles before sinking, it’s clear that the reckoning that night was somewhat off.

Boxhall grabbed the slip of paper with the coordinates, probably showed it to Chief Officer Wilde, and then took it to Phillips and Bride in the radio room.

There were no more jokes about SOS now. Jack Phillips was working the Marconi apparatus frantically, repeating the CQD again and again. But the very notion that the

Titanic

was sinking on her fifth night at sea must have seemed unbelievable to anyone on the other end of these messages. After all, just hours before, ships had been congratulating the

Titanic

on her maiden voyage.

In one exchange later that night, the

Titanic

’s sister ship, the

Olympic

, wanted to know if Captain Smith was steering southerly to meet up with them. But the

Olympic

was five hundred miles away. Phillips radioed back a terse message: “We are putting the women and children off in boats.”

But there was one young operator who did get it.

Twenty-one-year-old Harold Cottam was the only Marconi wireless operator working on the

Carpathia

. This ship, operated by the Cunard Line, was a ten-year veteran of the seas. She wasn’t built for luxury or to attract the rich. In fact, the

Carpathia

could hold only 100 first class passengers and 200 in second class. Most of the room was in steerage or third class, where 2,250 passengers could be accommodated.

Although Arthur Henry Rostron had served as the

Carpathia

’s captain for only a few months, he was an experienced seaman — competent, conscientious, and energetic. His nickname was “the Electric Spark.” The

Carpathia

had left New York on Thursday, April 11, a day after the

Titanic

’s departure from Southampton. Carrying 743 passengers, she was headed for England and then Italy.

Since he had no one to relieve him, Marconi operator Harold Cottam had already put in two long days of work. A few minutes later and he would have turned in.

“It was only a streak of luck that I got the message at all,” Cottam later told the

New York Times

, “for on the previous night I had been up until 2:30 o’clock in the morning . . . and I had planned to get to bed early that night.”

Harold Cottam had put on his coat, and was ready to leave the radio room, when he noticed messages being relayed to the

Titanic

from another long-distance relay station on Cape Cod. He decided to contact the

Titanic

to make sure the radio operators were aware of these messages.

Cottam was shocked at what Phillips radioed back: “Come at once. We have struck a berg. It’s a CQD OM. Position 41.46 N. 50.24 W.”

Harold Cottam replied, “‘Shall I go to the Captain and tell him to turn back at once?’”

The answer came instantly. “‘Yes. Yes.’”

Cottam radioed that he would inform the

Carpathia

’s captain. Immediately he set off to find Captain Arthur Rostron, who’d just gone to his cabin for the night. When he got the word, Rostron didn’t hesitate: The

Carpathia

would go to the rescue.

Usually the

Carpathia’s

maximum speed was about

fourteen knots. Captain Rostron would do his best to beat that. He said, “I immediately sent down to the Chief Engineer and told him to get all the firemen out and do everything possible.”

But Captain Rostron was taking a chance. His ship would face the same danger as the

Titanic

— ice.