To the Edge of the World

Table of Contents

IV - September 20-October 2, 1519

VI - October 25-November 24, 1519

VIII - November 25-December 22, 1519

X - December 30, 1519-January 13, 1520

XI - February 2-March 31, 1520

XVI - August 24-November 28, 1520

XVII - November 28, 1520-January 9, 1521

XVIII - January 9-March 6, 1521

XXV - September 4-October 27, 1521

XXVI - November 1-December 21, 1521

To Carl,

my love, my dearest love, always.

And to our sons,

Ian, Aaron, and Ethan.

May your lives be filled with adventure;

may you know the joys of courage,

of honor, and of love.

I

June 1519-July 1519

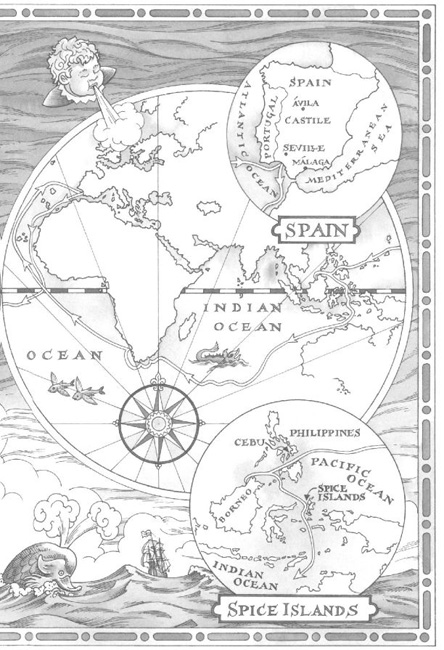

On the first day of June, in the year of our Lord 1519, I, Mateo Macías de Ávila, a Spaniard by birth, buried my parents.

An ugly dog watched. Spotted with mange, the dog lounged in the shadow of a nearby boulder, panting, his tongue lolling out of his mouth while I piled stone after stone upon their bodies. It did not take long before the sweat glistened on my body. The sun was fierce and no breeze blew. But I did not stop. I could not stop. I refused to stop, and my chest burned from the exertion.

I was determined. More determined than he. No dog would devour my parents. No dog would drag them through the city gates of Ávila like they dragged Juan Garcia, or young Catalina, to gnaw their flesh while the townspeople fled in horror. I threw a rock, but the dog dodged it deftly, ears flattened, returning quickly to his spot in the shade.

For much of the morning I worked, until finally I fell to my knees before the finished graves. “Father, Mother,” I prayed. “Rest in peace.” I reached out and touched the wooden crosses, caressed the names etched beneath my fingertips. I crossed myself and asked God to be merciful to their souls.

Afterward, I burned the farm.

My home. Dry, parched land, strewn with rock. A dusty courtyard, surrounded by a fence of sticks. A house of mud and stone. One room. A table. A chair. One rug. Two beds. A curtain dividing.

In spite of the heat, my eyes misted as I remembered. There beside the table, beside the planked surface where beeswax candles once burned, was where my mother read me poetry. To the pride of my father, she could read. “You will teach our son,” Tomás had commanded, drawing himself up to his full height, despite his bad leg. “My son is not a peasant. My son will be someone. Read, María, read.” My mother bent her head over her book, her only book, her voice soft as the flutter of birds’ wings. After, she always said, “Mateo, my son, sing me a song.” And I gladly fetched my guitar and sang while her eyes closed and my father tapped his good foot.

Now the table wavered with heat, and orange flames snapped and curled, devouring the curtain, the beds, the roof above my head. Smoke filled my nostrils and I stumbled backward out the door. I lay on my back in the courtyard, ashamed of my crying, not caring that the dog now lay panting beside me.

I lay like that until the fire drove me away. My possessions sat in a pile by the fence. I slung my guitar over my back and slipped my dagger into my waistband. I draped my mother’s rosary about my neck and picked up the book of poems, my sketchbook of drawings and box of inks (for my mother had also taught me to draw), and a goatskin filled with watered wine. Into my shirt pocket I dropped two pieces of bread, hoping they would not fall through the frayed hole. My father refused to allow my mother to sew patches on our clothing. “Only the poor do such things,” he said. And he was right. We were not poor.

I whacked the ugly dog on the nose with a stick, sending him howling, and tossed the stick into the fire. I watched until the only home I had known was but a blackened, crumbling shell.

By now the sun burned high in the sky. It was time to leave.

It took a long time to gather my father’s sheep, frightened away by the dog and the fire. There were ten sheep, but I found only eight. I feared to stay longer lest the dreaded pestilence that consumed Ávila—devouring neighbors, friends, parents—also consume me.

And so, with eight sheep and my few possessions, I turned my back on the town of Ávila, turned my back on the two mounds of stone beside the smoking ruin. I set my face to the south and began to walk.

On the afternoon of the next day, I realized I was being followed. Perhaps he smelled the one last piece of bread that had not been eaten. Perhaps he thought he could steal one of my father’s sheep. Or perhaps, and this at least I hoped was true, he despaired of digging at the graves of my parents. In any event, the ugly dog trotted behind me. Never close. But near enough so he shimmered in the heat, a speck of grime no bigger than a flea.

I ate my last piece of bread and drank the last of my wine. Then I checked my armpits for pestilence, then the sides of my neck and my groin. Nothing. I said the rosary.

The next day I turned fourteen years old. I lay in a ditch by a river, too hot, too weak to move. Never had I been so far from home. Never had I been so hungry.

When I awoke the next morning, the sheep were gone. Footprints marred the mud next to the river, and they were not mine. I looked everywhere and found only Ugly, lapping water at the river’s edge. Anger grew within me like water coming to boil and I hurled a rock at him. “You could have warned me!” I cried, tears of frustration rising in my eyes. “Next time I will stab you with my dagger!”

When Ugly disappeared in the distance, I lay in the ditch and waited for the pestilence to take me to my parents. Without my father’s sheep, I had nothing—nothing to sell, nothing to trade. I waited a long time to die. When the sun began to slide down in the sky, my stomach hurt worse than it had for days. Perhaps that was the first symptom. Again, I checked my armpits, my neck, my groin. Nothing. I did not say the rosary.

In the morning, when I knew I was not dead, I dragged myself out of the ditch and continued to journey southward.

At noon, I approached a monastery, nestled beneath the wing of a castle like a chick under a hen. From behind the monastery doors wafted a delicious aroma that made my stomach cramp with pain. I could stand it no more. To the ringing of the bell, I cast my glance to the ground and gathered in shame with others— ragged beggars, crippled children, one-legged soldiers—around a huge cauldron of soup. When my turn came, I dared to look into the face of the monk who handed me a bowl. Instead of the scowl I expected, I was met with a kindly look.

“May God bless you,” he murmured as he ladled the steaming broth into my bowl. Into my other hand he thrust a hunk of bread. I sat upon a rock, devouring my food, not caring that the soup burned all the way down. Only when I finished and sat licking my fingers of every drop, every spare crumb, did I realize Ugly watched me. Under his accusing stare, the soup suddenly turned sour, and I vomited.

I was angry with myself and wondered blankly if I should eat the vomit, but when Ugly began to devour it, I returned to the monastery. The entrance was closed and I banged on the doors. The same monk who had served me my soup and bread answered, and there was a glint of recognition in his eye.

“I have vomited my soup and bread.”

He disappeared and returned to give me another hunk of bread. But when I asked for more soup, my mouth watering and my belly aching to think of it, he said, “I’m sorry, but there is no more. We have given it all away. Come back tomorrow at noon.”

I did not argue, and when the door closed softly, I steeled my face and turned away. I will not wait until the morrow, I told myself. I will not allow him to serve me again. I shall move on to the next town.

On the morrow I sat outside another monastery with bread and a bowl of soup in my hands. I forced myself to eat slowly.

Ugly licked his lips and watched me with eyes I noticed were brown. Sad and brown. I let Ugly have a bite of bread and, after I finished the broth, set the bowl down and watched while Ugly licked it out. This time I did not vomit.

The next day, when instead of a monastery there stretched a vast, empty plateau, Ugly caught a rabbit and left it at my feet. A bloody, furry mess that we ate together.

And so we passed out of the plateau, out of the land of Castile, into the lower countries of which I had only heard tell. Many rivers we crossed. Shallow, starved rivers that dreamed of rain. Each time I fell beside the muddy water, drinking until my stomach tightened like a goatskin. Beside me, after drinking his fill, Ugly lay on his back, exposing his spotted belly to the heavens, a belly full and bloated like my own.

In one of these rivers I lost my dagger. I waded into the river with all my possessions, but upon gaining the other side, I found that my dagger was gone. After searching for the better part of a day I admitted it was lost. I sat upon the muddy bank and cursed my life. What is a man without his dagger?

The next morning, I entered a side pool and sat in its still waters. I checked my reflection for signs of pestilence, but no disease stared back at me. Instead I saw the image of a young man, swarthy like his father, stocky, with a mop of unruly hair and an undignified nose. After staring at myself, I decided I was not nearly so ugly as Ugly, and the thought made me smile, startling me when straight white teeth smiled back.

After feasting on another rabbit, we waded across the river, the dog and I, and many rivers after, until we came to a land that slowly turned green, a land that smelled faintly of orange blossoms, of food, of the sea.