Torch (32 page)

Then he screamed and came at Carver with what martial arts practitioners call a crescent kick, wheeling his body and leg sideways, his foot arcing with bullet speed toward Carver’s head.

But the injured leg slowed him enough for Carver to lean back and away. He felt the

swoosh

of air as Beni Ho’s foot flashed past his face. He lashed out with the cane but missed as the little man spun in a complete circle so fast he was a momentary blur.

The sudden action flushed fear from Carver. He thought he might die, but in the fatalistic core of him he wasn’t afraid. It had come down to mechanics.

Ho was on him again so fast he could react only by lifting his cane with both hands to try to block the downward chopping blow. The hard walnut cane split in half like balsa wood, doing little other than slowing the edge of Ho’s hand before it glanced off Carver’s shoulder, probably breaking the collarbone. Carver kicked out with his good leg and felt pain in his toe as it made contact with Ho’s shinbone. It was Ho’s injured leg, and the little killer’s smile was replaced by a look of annoyance as his backhanded elbow blow at Carver missed and he staggered toward him. The mental repose of the trained assassin had momentarily been broken by surprise and pain. Carver kicked the leg again, this time the thigh where the bullet had entered, losing his footing and falling hard onto his back. The unbalanced Ho grunted and stumbled, beginning to fall. So quick and agile was he that he managed to change the direction of his fall so he’d land on top of Carver. In midair he was already drawing back his hand to strike what would be a lethal blow to the throat.

Carver raised the splintered cane and it entered Ho’s chest below the sternum. The hand thudded into the carpet near Carver’s head. Ho’s face was inches from Carver’s, grinning with shock, the eyes just beginning to register what had happened. He grunted but couldn’t rise. Tried a straight blow with his knuckles that bounced off Carver’s forehead and didn’t hurt much. Carver twisted the cane and shoved on it at an angle to the heart, letting Ho’s weight help drive it deeper. He felt the warm blood on his fists and between their bodies spread.

The little man thrashed wildly and ineffectually, then made a deep, animal sound in his throat and went limp. He sighed, blood frothing at the corners of his grin, and lay in the stillness and silence of death.

The rhythmic hissing sound Carver heard was his own breathing as he came back from the primitive place where he’d been, where all creatures think only of survival.

Ho seemed as light and small and harmless as a child as Carver lifted and rolled him to the side. The countless eight-by-ten glossy head shots of models on the wall smiled down at the scene of mayhem and death as if it were a setting requiring them to register confidence and glee. Carver propped himself up on his elbows, then struggled to a sitting position. He was aware now of a ringing in his ears.

Then its pitch changed and he recognized the distant warbling of sirens. He realized what had happened. Beth had figured it out, too. Or McGregor. Probably Beth, who’d then called McGregor.

Walton had heard the sirens, too. The door with his name on it opened and he came out in a hurry. He said, “Beni, you hear—”

Then he saw what had happened and he stared down at Carver. His lips worked, making his thin, bristly gray mustache writhe like a caterpillar dying in the sun. “I’ve got a gun in my desk drawer,” he said. “I oughta kill you.”

Carver said, “Murder’s more serious than seduction.”

Walton stood thinking about that. The kind of legal help he could afford wouldn’t be able to let him walk, but with Ho dead and unable to testify, Walton almost certainly could avoid a homicide charge. The dead could be a convenience in court.

The sirens grew louder and were now obviously heading in the direction of the agency.

Walton stared at Carver for almost a full minute, turning it all over. There were possibilities, even with time running out fast, but none of them were good ones.

Then his broad shoulders slumped and he went to the reception desk and sat down in the chair behind it. He picked up the phone.

Carver thought he was going to call the police, maybe dream up a story about how Carver had barged into the agency and tried to kill him.

But he called his attorney instead.

C

ARVER WATCHED THE

ocean and let his thoughts roll with the waves. Beth was revising her final installment on the Walton Agency story for

Burrow

on her laptop. They were sitting on the cottage porch, side by side in the webbed aluminum chairs. It occurred to Carver that old married folks sat like that on their porches, though not usually with a computer.

A sailboat banked gracefully into the wind near shore. Beyond it the low profile of an oil tanker, its scooplike hull long and low on the horizon, its superstructure well back on the bow, moved almost imperceptibly through the morning haze like a mirage. A gull soared in close to the cottage, screamed, and glided to the beach to touch down near foam fingers of surf. The warm breeze carried the fetid and fishlike smell of the sea, a reminder of life and death and forever.

“I write this stuff,” Beth said, looking up from the computer, “and I get mad all over again at Walton.”

Carver knew what she meant. Marriages that might still be intact, people who might still be alive, had fallen victim to Walton and his experienced and skillful employees. He said, “There’s something particularly unfair about the business he was in. Husbands and wives who might never have strayed didn’t stand much chance under the pressure of expert seducers who knew the most intimate details about them.”

“I don’t exactly buy into that, Fred. The spouses have gotta share the blame.”

“Kind of an uneven match, though,” Carver said, thinking for a moment of Maggie Rourke. Beautiful, almost irresistible Maggie. “I feel sorry for them.”

“So do I. But the forbidden fruit was rolled their way, and they’re the ones who picked it up and bit into it. Their gamble, their loss, their responsibility.”

“Even Donna Winship?”

“Even Donna.”

Carver glanced over at her impassive dark features. She amazed him sometimes by being even more uncompromising than he was. But then she’d survived by not compromising about certain things, by keeping a part of herself whole at the center of the damage.

It was surprising how often uncompromising people, if they were discriminative in their choice of battle, were ultimately proved right.

It was called character.

We were here and then gone in this world, and character was the thing that made a difference, that made it all mean something.

“Anyway,” she said, “Walton’s doing time, and most of the spouses are going back to court and setting their divorces right, sometimes filing criminal charges for fraud.”

Carver watched the sailboat tack out to sea, toward silver spokes of sunlight angling down through breaks in mountainous white clouds. Sometimes Florida could be a postcard.

“Speaking of wronged spouses,” Beth said, “Charlie Post phoned here yesterday asking for you.”

“Am I supposed to call him back?”

“No, he’ll call you. He wants to sell you a yacht.”

Carver grinned. The sailboat appeared to enter the radiant columns of sunlight and shimmered in the distance as if transformed inside a brilliant cathedral of light.

He watched it until it disappeared in the bright haze.

Here and then gone.

John Lutz is one of the foremost voices in contemporary hard-boiled fiction.

First published in

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine

in 1966, Lutz has written dozens of novels and over 250 short stories in the last four decades. His earliest success came with the Alo Nudger series, set in his hometown of St. Louis. A meek private detective, Nudger swills antacid instead of whiskey, and his greatest nemesis is his run-down Volkswagen. In his offices, permeated by the smell of the downstairs donut shop, he spends his time clipping coupons and studying baseball trivia. Though not a tough guy, he gets results. Lutz continued the series through eleven novels and over a dozen short stories, one of which—“Ride the Lightning”—won an Edgar Award for best story in 1986.

Lutz’s next big success also came in 1986, when he published

Tropical Heat

, the first Fred Carver mystery. The ensuing series took Lutz into darker territory, as he invented an Orlando cop forced to retire by a bullet that permanently disabled his left knee. Hobbled by injury and cynicism, he begins a career as a private detective, following low-lifes and beautiful women all over sunny, deadly Florida. In ten years Lutz wrote ten Carver novels, among them

Scorcher

(1987),

Bloodfire

(1991), and

Lightning

(1996), and as a whole they form a gut-wrenching depiction of the underbelly of the Sunshine State. Meanwhile, he also wrote

Dancing with the Dead

(1992), in which a serial killer targets ballroom dancers.

In 1992 his novel

SWF Seeks Same

was adapted for the screen as

Single White Female

, starring Bridget Fonda and Jennifer Jason Leigh. His novel

The Ex

was made into an HBO film for which Lutz co-wrote the screenplay. In 2001 his book

The Night Caller

inaugurated a new series of novels about ex-NYPD cops who hunt serial killers on the streets of New York City, and with

Darker Than Night

(2004) he introduced Frank Quinn, whose own series has yielded five books, the most recent being

Mister X

(2010).

Lutz is a former president of the Mystery Writers of America, and his many awards include Shamus Awards for

Kiss

and “Ride the Lightning,” and lifetime achievement awards from the Short Mystery Fiction Society and the Private Eye Writers of America. He lives in St. Louis.

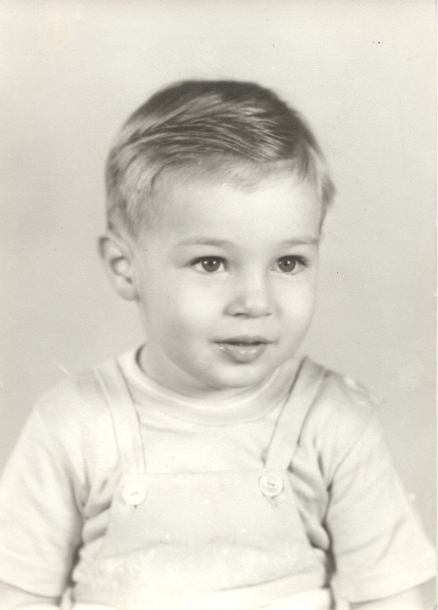

A two-year old Lutz, photographed in 1941. The photograph was taken by Lutz’s father, Jack Lutz, who was a local photographer out of downtown St. Louis.

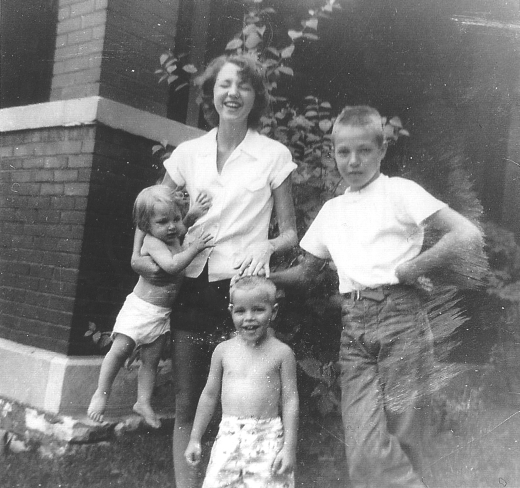

A young Lutz with his little brother, Jim, and sisters, Jacqui and Janie.

Lutz at ten years old, with his mother, Jane, grandmother, Kate, and brother, Jim. Lutz grew up in a sturdy brick city house that sat at an incline, halfway down a hill; according to Lutz, this made for optimal sledding during Missouri’s cold winters.