Traveling Soul (33 page)

Authors: Todd Mayfield

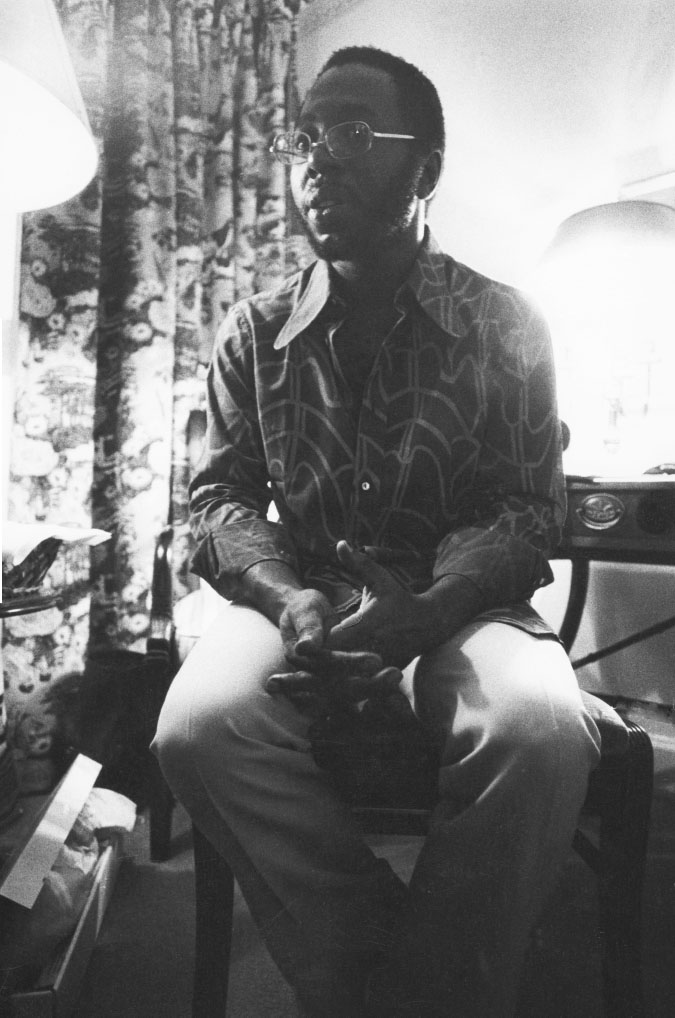

Curtis at the Berlin Hilton, West Germany circa 1973.

AUTHOR'S COLLECTION

Curtis in London circa 1973.

COURTESY MICHAEL PUTLAND

Curtis at the Montreux Jazz Festival 1987, Switzerland.

AUTHOR'S COLLECTION

Curtis on the Impressions' 1983 reunion tour.

COURTESY MICHAEL PUTLAND

Curtis and Todd after 1994 Grammy Awards. Curtis received the 1994 Legend Award.

JIM MCHUGH

Move On Up

“Top billing now is killing,

For peace, no one is willing.”

â“(D

ON

'

T

W

ORRY

) I

F

T

HERE

'

S A

H

ELL

B

ELOW

, W

E

'

RE

A

LL

G

OING TO

G

O

”

C

hicago, 1970

âThe decade dawned under dark clouds. Nixon, swept into office with promises of a return to law and order and an end to the Vietnam War, delivered neither. The year turned foul almost immediately. In February, the Weathermen hurled Molotov cocktails all over New York, the Black Liberation Army allegedly bombed a police station in San Francicso, and racists in Colorado bombed school buses that were being used to desegregate a Denver school. Three months later, race riots broke out in Georgia, the Ohio National Guard killed four students at Kent State, and police killed two students during an antiwar rally at historically black Jackson State College in Mississippi. In the music world, Motown's Tammi Terrell died of brain cancer in March, the Beatles disbanded in April, and Diana Ross released her first album without the Supremes in May. Meanwhile, boys in body bags came home in heaps as the death toll in Vietnam mounted.

Amid the carnage, my father wrote, produced, and fronted his final Impressions album,

Check Out Your Mind

. The title track foreshadowed the new direction of his writingâdark, rhythmic, driving. It matched

the paranoia eating away at Dad's generation. The new sounds benefitted from a subtle shift in personnel. Johnny Pate had moved to New York to work for Verve Records, and now my father brought in two other arrangers, Riley Hampton and Gary Slabo.

Hampton was known as

the man

in Chicago for scoring strings. He did extensive work for OKeh during Curtis's tenure there as staff writer and producer, and he worked for Vee-Jay, the Impressions' first label. Hampton also arranged for Motown, and most famously, he worked with Etta James at the pinnacle of her career. His arrangement on her version of “At Last” remains one of the most famous string scores in pop music history.

Hampton tended toward languid, pretty string lines. When those lines mixed with Slabo's punchy, insistent horns, the effect became eerie and schizophrenic. It still had the Chicago Sound, but instead of the jazzy swing of Johnny's arrangements, it was more straightforward, funky, and gripping.

The sound complemented the times perfectly. Soft drugs like marijuana and psychedelics like LSD had fallen out of fashion; heroin and cocaine now dominated the scene. These drugs had teeth in a way the peaceful drugs of the '60s didn't, and they devastated the black community. Many a black soldier copped them in Vietnam and brought them home, where mind-numbing substances helped cope with the haunting specter of war alongside the soul-crushing despair of the ghetto.

Uncle Kenny never got into that scene, but he recalls the brutal mixture of war and drugs he encountered in Vietnam. “Over there you could get the purest stuff,” he says. “You could always tell when you were going to get hit because you could smell the opium in the air. I have shot somebody with a fifty-caliber machine gun, half his body's gone, and he's still trying to get to me. I've seen guys get so high, they watch a man come in to kill them.”

Black soldiers like Uncle Kenny had to deal with double rejection on their return home. Not only did the militant antiwar crowd greet them with hateful sneers, the country for which they risked their lives still refused to accept their humanity and respect their basic rights. Five

heavy years had passed since the Civil Rights Act, and it seemed nothing had changed but the law. Reality remained rigged against black Americans. Many retaliated.

A

Time

magazine poll in 1970 found that more than two million black Americans counted themselves as “revolutionaries” and believed only a “readiness to use violence will ever get them equality.” The poll also showed that the number of those who believed blacks “will probably have to resort to violence to win rights” had risen 10 percent since Malcolm X's assassination. Meanwhile, the Black Panthers continued gaining support even as their organization fractured. Newton said, “Every one who gets in office promises the same thing. They promise full employment and decent housing; the Great Society, the New Frontier. All of these names, but no real benefits. No effects are felt in the black community, and black people are tired of being deceived and duped.”

Check Out Your Mind

hinted at the way my father would deal with these depressing changes. The album pushed the Impressions further into funk than they'd ever gone with the singles “(Baby) Turn On to Me” and “Check Out Your Mind,” which hit numbers six and three, respectively, on the R&B chart. The album was a good effort, although it only rose as high as twenty-two R&B and missed the pop chart. Still, it sold based on the power of the singles. Curtom had another hit to its name.

The album's release deepened fractures within the group. While Fred and Sam always stood behind Curtis's songs, neither liked “Check Out Your Mind.” Fred, who spent so many late nights listening to my father pluck out new songs in his hotel room, saying, “Curtis, you just wrote us another hit,” couldn't say the same about “Check Out Your Mind.” “That was a tune that I didn't really care about,” Fred said. “I don't know what he was thinking where writing that song was concerned. But it never killed me.”

That particular track also illustrated the musical reasons my father needed to go solo. Having to account for three voices didn't give him room to do much but sing on the beat. He couldn't deliver lines in idiosyncratic ways that came to him spontaneously because he had two other

guys whose job was to follow his lead. As a result, it changed the subtext, the attitude, and the meaning he could imply behind his lyrics. He needed to be funkier, freer. While the interplay among the three voices added power to a song like “People Get Ready,” it detracted from the funky grooves Dad wanted to explore.

He felt ambivalent. On one hand, he said, “Of course, the Impressions were just the perfect bunch of fellas to be able to express yourself.” On the other, he said, “Not being with the Impressions allowed me, in my mind, to be more free about things I felt I had to say. It was more risky for the Impressions to sing songs like âChoice of Colors' and âWe're a Winner.' For getting airplay, that wasn't the norm. I didn't mind taking those chances myself, but I was always concerned of the fellas' feelings.”

As the Impressions finished recording

Check Out Your Mind

, Dad decided to leave the group. He didn't say anything, but he began writing songs for his first solo album, more self-confident than ever, and conscious of the anger fueling the militant surge in black culture. He was also conscious of another feeling in himselfâafter touring

Young Mods

, he wanted to focus on building Curtom. The constant slog of touring always weighed heavy on him, and by focusing on the label, he saw a way to shuck that weight while keeping his career moving forward. As he said, “I've been on the road for twelve or thirteen years now and I can't recall living in my hometown for any more than three months at one time. I've never been in Chicago for one whole year since I've been in the business. You know, I'm born under the star Gemini and they are supposed to be very changeable people. So I'm making a change to try to do other things.”

Midyear, he made his break. Nothing happened to force his hand, no dramatic falling out or heated argument. In his customary seat-of-the-pants way, my father simply picked up the phone one evening, called Fred, and said, “Fred, I'm going to try to go on my own and see what I can do. You and Sam can do the same thing. Y'all go on your own and see what you can do.” Fred called Sam and told him the news, and that was it. My father left the group.

Fred, Sam, and the Impressions, three of the most important forces in Dad's life for more than a decade, no longer occupied his mind. The boyhood dreams, the endless miles traveled in the green station wagon, the lonely nights trying to steal sleep in motel beds, the harmonizing and fraternizing all came to an end. Dad struggled with the decision. “Leaving the Impressions was a lot like leaving home,” he said. But he knew he was right. “When the time is right, you have to go. You need to make it on your own.”

Even though their split had been building since the dissension over owning shares of Curtom, it still stung. Fred said, “I felt bad for a simple reason: I had a family, Sam had one, and we always looked to Curtisâhe was a great writer, and you've lost that now, so what do you do? You can't never replace a Curtis Mayfield.”