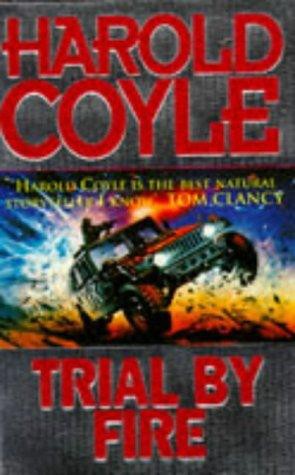

Trial By Fire

On the Texas-Mexico border

27 June

In the gathering darkness, the predators of the night began to stir. From burrows, holes and crevices, the creatures of the desert crawled, slithered, or scurried from their habitats into the cool of the late afternoon. For the next several hours they would seek, strike, and consume those things that would allow them to survive another day in their harsh environment.

It was a cruel existence that demanded something die so that something live. There was no grand plan or reason for such things. Nor was there compassion, feeling, or regrets. Only survival.

From one of thousands of holes dotting the barren desert floor, a scorpion sallied forth. Like a missile being released from its launch tube, the scorpion moved forward mechanically, purposefully, unstoppably.

As it cleared the narrow confines of its hole, the scorpion prepared to kill.

Once it was free to do so, even before its head was in the open and able to see, the scorpion swung its massive right claw out, and then the left.

There was no pause, no hesitation as the scorpion continued to move forward, finally clearing its tail. Like the fin of a missile, the tail automatically deployed into a fully erect position. Unlike the fin of a missile, the tail was more than a there accessory; it was the scorpion’s main weapon. The stinger at the end of the tail was, for now, curled under, but ready.

As if the scorpion had known where it was going before it left the dark hole, it continued straight ahead into the gathering darkness. As it did so, for a brief moment, the long shadow of an eagle flashed across the scorpion. There was, however, no danger to the scorpion. The eagle was not seeking so small a creature. Instead, the large powerful bird had its senses tuned to seek what it needed to survive. Flying high above the desert floor, the eagle scanned the barren terrain for other prey. The small, seemingly insignificant scorpion, moving about in the long shadow of the eagle’s powerful wings, never caught the bird’s eye.

If the crossing of their paths was an accident, their purpose was the same. Each sought that which would allow it to survive, to continue. That those two particular creatures of the desert would ever meet, let alone come into conflict, or even cross paths again, was improbable at best. But in a harsh and cruel world where killing meant survival and survival was all that mattered, everything that could do so pursued that goal unhesitatingly.

So anything was possible.

And if something is possible, then it will be, if only in a dream, or a nightmare.

The Service isn’t what it used to be—and never was.

—Service saying

Manning Mountain, Fort Hood, Texas

0645 hours, 28 June

Perched upon a flat rock, Captain Stan Wittworth lazily ate his breakfast of cold ham and chicken loaf while he watched to the south. A cedar tree, its growth stunted by the Texas heat and lack of water, gave some protection from the sun, but did little to protect Wittworth from the heat. The heat of a new Texas day, less than an hour old, was already oppressive, soaking Wittworth’s BDUs with sweat. Within two hours the heat would be unbearable.

From his Humvee parked in a concealed position behind Wittworth, the blaring of a radio speaker announced the beginning of a report.

Identifying the radio call sign as that of the platoon leader of his 2nd Platoon, Wittworth stopped eating and listened. The report announced that they had cleared checkpoint one-four without any contact and were proceeding north. Looking down at a map of Fort Hood’s maneuver area laid out at his feet, Wittworth looked for the blue symbol that identified checkpoint one-four. He found it at the point where Old Georgetown Road crossed the Cowhouse Creek. Popularly known as Jackson’s Crossing, it was indeed a critical point to any force attacking north or south.

Reaching the Cowhouse and crossing it unopposed would give the 2nd Platoon a decided advantage in the upcoming engagement.

Leaning the brown aluminum-foil package that contained his ham and chicken loaf against a rock so that the contents wouldn’t spill, Wittworth lifted his binoculars to his eyes and looked for the vehicles of the 2nd Platoon. Though he couldn’t see them, the dust clouds thrown into the still morning air by the tracks of its vehicles marked their progress.

Unless the tank company undergoing evaluation reached the point where Wittworth was sitting in the next ten minutes, his 2nd Platoon, playing the role of the opposing force, or enemy, would be here instead. The tank company, instead of holding superior firing positions such as the one Wittworth’s Humvee was in, or fighting the 2nd Platoon in the open ground between Manning Mountain and the Cowhouse, would have to fight in the cedar forest on top of Manning Mountain. In a fight on the mountain, in the woods, the 2nd Platoon would be able to use its infantry against the tanks in close terrain. That was what Wittworth was hoping for. In a fight in the open terrain of the Manning Mountain Corridor below, the 2nd Platoon’s four M-2 Bradleys, with its infantry, would be eaten alive by the fourteen tanks rolling down from the north.

Wittworth watched Old Georgetown Road intently for the first of the 2nd Platoon’s Bradleys to roll into the open. In the distance, he could hear the Bradleys’ high-pitched whine. Suddenly, however, the sound changed, almost dying out. Searching the tree line on either side of the road where the 2nd Platoon should have been emerging, Wittworth saw nothing. Even the large dust cloud was dissipating. That could mean only one thing; Lieutenant Shippler was stopping to regroup and deploy before crossing the open area at the base of Manning Mountain. Slowly dropping his binoculars from his eyes, Wittworth unconsciously began to shake his head, mumbling and calling Shippler every foul name he could think of.

Instead of being bold and rushing for the high ground, Shippler was exercising great textbook caution. Unless the tank company commander, moving south along Old Georgetown Road from Royalty Ridge, had a severe case of the slows, he would reach the southern edge of Manning Mountain and gain superior positions from which he could engage the 2nd Platoon as they moved north across the open area below.

As if drawn by Wittworth’s dismal thoughts, the cracking of dry cedar branches being crushed under the treads of M-i tanks and the squeak of steel drive sprockets announced the arrival of the tank company. Turning, Wittworth caught glimpses of the green, brown, and black camouflage paint of an M-1 tank as it slowly picked its way through the cedar trees toward the edge of Manning Mountain. The tank’s commander, standing waist-high in his cupola, was leaning forward, watching the right front fender as he directed his driver forward through the trees. The tank’s loader was also riding high out of his hatch, located on the turret’s left side. Like his commander, he was leaning forward, watching that the left front fender cleared the trees. It was obvious that the tank commander had been there before, for he neither referred to a map nor stopped and dismounted his loader to move forward to recon a spot for the tank. It didn’t take officers and NCOs of the armor and mech units stationed at Fort Hood long to figure out that there were only so many ways to skin the cat when maneuvering on Manning Mountain.

Ignoring Wittworth and his Humvee, the tank commander pulled into a position to the left of where Wittworth sat. When the tank was where he wanted it, the tank commander ordered his driver to stop. As the driver throttled back and locked the brakes, the commander dropped down in his cupola, snatching up a pair of binoculars that had been tied to the cradle of his .50-caliber machine gun, and began to scan the far horizon. The turret also began to move slowly, from left to right, as the gunner began his search for targets. Even the loader watched for telltale signs of the enemy.. The movement of one of Shippler’s Bradleys simplified their task.

Like a hunting dog who has spotted game, the tank’s main gun suddenly jerked to one side, then froze once it had its prey in sight. Even before the gun stopped moving, the tank commander, no doubt alerted by the gunner’s acquisition report, had already disappeared into the tank where he could use the commander’s extension of the tank’s primary sight to control the engagement. Wittworth stood up, watching the tank prepare for action. Then he turned to the south, scanning the tree line where Shippler’s platoon had disappeared. In the distance, Wittworth could see a Bradley move out from the tree line and begin to angle to the left toward Old Georgetown Road.

That maneuver presented the M-i tank next to Wittworth with a good quartering shot. But the tank commander was in no great hurry. He knew Bradleys rarely traveled alone. To kill the first one would only have served to warn the others that they were in danger. So he and the other tank commanders in the tank company, who had moved into fighting positions along the lip of the ridge after him, watched and waited. Just as the first Bradley reached Old Georgetown Road, their patience and discipline were rewarded as a second Bradley broke out of the tree line and began to follow.

Watching, Wittworth hoped that the tanks would fire soon. It was obvious that Shippler was using one section of two Bradleys, still in the tree line, to overwatch the movement of the two Bradleys now moving toward the road. While the two Bradleys in motion would have little chance of surviving the initial volley of fourteen tanks, at least the stationary Bradleys in overwatch would be able to return fire and take out one or two of the offending tanks. But even this hope was soon dashed as Wittworth and the tanks now lining the southern edge of Manning Mountain watched the last two Bradleys of Shippler’s platoon come trundling out of cover and into the open. As if they had all the time in the world, the last two Bradleys began to move toward the road to join the others already there.

Still, the tanks held their fire. Every second they waited drew the Bradleys away from cover and closer to the tanks. With the

MILES

laser engagement system, the ideal killing range for the tanks was 1,000 to 1,500 meters. A well-trained crew with their

MILES

device well bore sighted and zeroed and with fresh batteries could score a kill out beyond 2,000. But this tank company commander wasn’t taking any chances. He didn’t need to, for Shippler’s platoon, now formed in a wedge on either side of Old Georgetown Road, was gradually closing the range.

To Wittworth, it was like watching a bad movie, or a play that showed the actors casually walking into a trap that the audience knew of but couldn’t do anything about. Unable to watch his own platoon any longer, Wittworth looked over at the tank to his left. The tank commander was hunched down in his cupola with only his head and shoulders showing.

As he watched the oncoming Bradleys without the use of binoculars—for there really was no need for them anymore—the tank commander spoke into his intercom microphone. There was no way for Wittworth to tell if he was giving last-minute instructions to his gunner or simply engaging in idle chitchat in an effort to pass the last few nervous seconds before they fired.

From the corner of his eye, the tank commander caught Wittworth staring at him. Ending his conversation with the unseen crewman, the tank commander turned to Wittworth. With the broadest, toothiest grin he could manage, the tank commander looked at Wittworth and gave him a thumbs-down, meaning that the Bradleys were about to die. This gesture pissed Wittworth off, and the tank commander, knowing who Wittworth was, meant it to piss him off. Wittworth could feel the blood rushing to his head and the hair rising on his neck as he shot a glare that could have burned through the tank’s armor plate.

Wittworth’s rage was still building when the tank commander’s grin disappeared. Leaning forward, the commander’s right hand went up to his helmet. For a second, he stood there like that, listening to something coming in over his earphones. It had been a radio call, for Wittworth saw his right thumb push the transmit lever forward into the position for transmitting over the radio. The tank commander shouted something into the mike, stopped, pushed the transmit lever to the rear, or intercom position, and shouted something to his crew. Turning from watching the tank commander, back to Shippler’s platoon, Wittworth realized that the tank commander had, in all probability, just received the order to fire.

Shippler’s platoon was about to be engaged.

From hidden positions along the southern edge of Manning Mountain, half a dozen loud booms announced the beginning of the engagement.

Below, Shippler’s platoon continued forward for a few more seconds.

Then the

MILES

receivers on the Bradleys began to register hits and near misses. Even before they knew for sure whether or not they were “dead,”

two of Shippler’s Bradley commanders cut on their on-board smoke generators and began a sharp 180-degree turn in an effort to hide in their own smoke. The other Bradley commanders, seeing the two turn away, also cut on their smoke generators and turned.

From where he stood, Wittworth listened to the radio in his Humvee tuned to Shippler’s command net for the initial report. There was none.