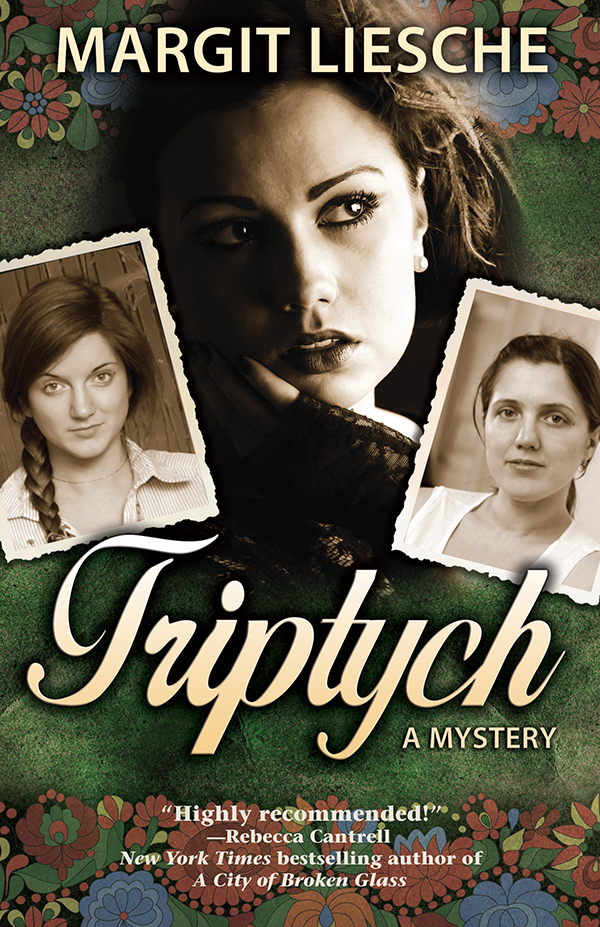

Triptych

Authors: Margit Liesche

Copyright © 2013 by Margit Liesche

First E-book Edition 2013

ISBN: 9781615954568 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

“Take A Chance On Me”

Words and Music by Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus

Copyright (c) 1977, 1978 UNIVERSAL/UNION SONGS MUSIKFORLAG AB

Copyright Renewed

All Rights in the United States and Canada Controlled and Administered by UNIVERSAL - SONGS OF POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL, INC. and EMI WATERFORD MUSIC, INC.

All Rights Reserved Used by Permission

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation

“Fernando”

Words and Music by Benny Andersson, Bjorn Ulvaeus and Stig Anderson

Copyright (c) 1975 UNIVERSAL/UNION SONGS MUSIKFORLAG AB

Copyright Renewed

All Rights in the United States and Canada Controlled and Administered by UNIVERSAL - SONGS OF POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL, INC. and EMI WATERFORD MUSIC, INC.

All Rights Reserved Used by Permission

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

Contents

In loving memory

Szeretettel emlékezem

Natalia Kunos,

née

Liesche

(1912-2005)

Maria (Manci) Hetlinger

(1925-1946)

Budapest, 1986

I turn back to admire the eighteenth-century Rókus chapel for a final time. The chapel's yellow-painted façade is ornamented with white Baroque figures of saints and a pair of arched wooden doors. To the right, tucked into the far corner of a recessed wing, is another door embellished with Baroque plaster trim. Near it, a large stone cross. Someone has placed fresh-cut flowers at its base.

“Lovely,” I say out loud.

A few people mill about in the open space before the chapel. My eyes stray to the person studyzesing the cornerstone.

There.

I'm still being followed.

You're in a Communist country, not midwest America, land of the carefree,

I remind myself for the umpteenth time since arriving. In the sixties, before her terrible death, my mother had travelled to Budapest. She had been tailed by KGB, her sister's apartment secretly searched, and her own luggage rifled through. Now here I am following her lead, determined to find the information she had stumbled upon. If that warrants a full-time KGB team of my own, so be it. What my mother learned may have killed her, and I have come too far to let them daunt me.

I start to turn away, then halt, puzzled.

My follower is walking briskly away from me toward the side door near the cross. A stop at the cross, head bowed as if in prayer, a quick sideways glance in the direction of the chapel and plaza, then off again, going for the door, pulling it open just enough to squeeze inside. But not before I recognize my follower's face. A circle within a circle interlocks. A shocking click.

My knees are liquid. I shudder.

“â¦never allow a murderer of loved ones to go unpunished.”

At the cross, I too bow my head, duck inside.

I stand in an unadorned hallway with only one way to turnâleft, toward the chapel. At the entrance to the nave, a sign on the corridor wall is written in Hungarian. I know the words

Szombat,

Saturday, and

Vasárnap

, Sunday, and there are worship service times underneath, but there is also a line in bold large print I cannot interpret. Perhaps the chapel is closed?

The door is unlocked. I enter the small nave. Light seeping in from the windows to my left allows only a shadowy impression of the room. Wooden pews. A simple altar framed by a soaring arched opening. On one side of the arch, a muted painting of Christ laying his hand on a kneeling supplicant; on the other, a replica of Saint Anne with Madonna as a child, the work of art familiar from St. Elizabeth's in Chicago.

The place is utterly quiet and completely still.

I concentrate on the cave-like space surrounding the altar, trying to sense what might be behind the sides enclosed by the walls of the arch.

“Anyone there?” I call toward the altar.

Silence.

I venture deeper inside, my ears tuned to the eerie quiet, my skin tight with fear. To my right is a carved wooden nook. Inside, a robed figure on a pedestal holds a child in his arms. Saint Rókus.

At the statue's base is another container of fresh-cut flowers. Calla liliesâmy mother's wedding bouquet. I stare. A piece of jewelry has been left beside the vase. The blood freezes in my veins. I walk over and lift the familiar piece, its chain trailing from the pedestal.

Behind me, a hushed voice whispers, “Ildikó.”

The piece slips from my fingers, hits the stone floor with a sharp crack.

Budapest, 22 October 1956

The school director opened the door to his office. A hard squeeze to the back of the girl's neck, and she lurched forward. The door clicked shut behind them.

Waiting beside a dark wooden desk was a stout woman with red hair, a pockmarked face, and fat lips. The heating system was going full throttle, the windows wide open. Ãvike thought of the extravagance, the waste. But then the woman immediately shut the windows.

“Major Gombóc is our revered guest,” the director said, introducing the red-haired woman.

For a moment, Ãvike was confused.

Gombóc

, Hungarian for “dumpling.”

On Ãvike's birthday, her mother always made s

zilva Gombóc

, the plum dumplings, fat and doughy, smothered in bread crumbs. A month ago, on her eleventh, even in these difficult times, her mother had managed to scrounge up the ingredients to make them. She could almost taste the yeasty flavor coupled with the heavenly sweet plum juice.

The woman cracked her knuckles, something Ãvike's mother forbade her to do: “It will make them big, like a boxer's.”

“We should like to be alone,” Gombóc said.

The director's voice turned cloying. “Naturally. Take your time.” He bowed from the waist, then rushed off to “attend to other important school business.”

Gombóc?

she thought again. But the woman's accent was clearly Russian. A false name then? To match the overly eager phony smile?

Yes, the major's body resembled a dumpling, but there was nothing soft about her expression. Ãvike caught her harsh blank look before taking a seat as directed. The pasted-on smile? No longer.

It was her first visit to the director's office. Now, observing the surface of his desk, it surprised Ãvike to discover that the head of the school did not seem to have any work. It was completely bare except for a lamp with a flexible arm. Across from her, the chair cushion squeaked noisily as the major, seated now, leaned forward, adjusting the metal shade until the bulb shone directly on Ãvike.

Ãvike blinked against the glare, struggling to see the woman's face. Only thick lips and the faintly whiskered flesh surrounding them were illuminated.

“Tell us,

kis

, little comrade,” the major said in her syrupy voice, beginning the long line of questions that followed.

What are the names of your parents? Where do you live? How long have you lived there? Is there a picture of Comrade Stalin in your home? What radio stations do your parents like best? Do they read? Lenin?

Western literature?

On and on it went. Just like in the dark of night, in the basement of her family's apartment building, where her mother had groomed her for just such a moment. “Ãvike, never trust anyone outside of your father and me,” she had warned. “Neighbors, your best friend.

No one

. Especially do not trust your teachers.”

Her mother had said that the teachers used children to spy on parents. So at night, as part of the evening ritual, they role-played. Now, in the director's office, seated across from Gombóc

,

she was aware of just how prescient her mother had been, and how well she had learned her lessons. She would give Gombóc nothing that might betray her parents' true political leanings.

Ãvike's back was to the clock on the wall behind her, but she guessed a half hour had passed. Her mouth had repeatedly gone dry and several times the questions halted so she could take the water the woman had liberally poured, perhaps thinking it might lubricate her tongue.

Finally, “The evening of 19 October, you and your mother were observed entering the Technical High School Hall in Buda. What were you doing there?”

Ãvike had been aware of the perspiration gathering on her upper lip. Now she felt a bead rolling down the side of her mouth. Her tongue longed to catch it.

Her mother, a graduate student attending classes in the evening, afterward worked the midnight to 5 a.m. shift at a bakery. Ãvike's father was a glassblower at a medical laboratory equipment manufacturer, his shift beginning shortly after her mother's ended. This left his evenings free for study, attending the occasional class, and watching over his daughter.

Despite her full schedule, Ãvike's mother found time to attend the meetings of PetÅfi Circle, a student discussion group. On nights when her father was otherwise occupied, Ãvike tagged along willingly. Being bored was better than being left alone. Her mother warned repeatedly, “The AVO, we never know when they will come.”

AVO, Allam Vedelmi Osztag. State Protection Detail. Secret police. Terrorists. Murderers

.

Ãvike loved to draw, but paper, pencils, they cost money. And there were never enough

forints

to go around in her family. The last few times she'd accompanied her mother to meetings, her mother had errands to take care of at a print shop. The man who ran the store was friendly and on each visit, he'd given Ãvike some paper samples. He even had a pencil, a new one, he insisted she keep. With the tools in hand, the sessions passed more quickly as she sat quietly at the back of the room, drawing and half-listening while her mother debated politics with other studentsâpoets, writers, painters, scholars. The gathering places varied, but the grievances remained constant: poor economic conditions, low wages, Soviet oppression.

Across from her, Gombóc glared. “What were you doing there?” she repeated.

Ãvike stared back levelly, even as from somewhere deep inside her brain student voices shouted:

What are we doing? Fighting for a liberal Hungarian Communism divorced from Russian domination. Struggling to keep Hungarian wealth in the country where it belongs. Trying to send the AVO, their terror, and hammer and sickle back to Russia!

Ãvike blinked.

“My mother was there because she is studying law in university, should like to be a lawyer,” Ãvike replied. “We are poor. She cannot pay someone to watch me. She must take me everywhere with her. She attendsâ¦

we

attendâ¦every class possible.”

“Class?” The sudden loud creak of the director's chair nearly sent Ãvike rocketing from hers. Her anxiety escalated as the major's fleshy face plunged forward, momentarily blocking the beam of light. Ãvike did not flinch.

Major Dumpling's voice turned icy. “What else?”

“Nothing else. My mother is a student. She is enrolled in many classes.”

A penetrating look, then Major Gombóc stood and left the room.

The shaft of light remained aimed at Ãvike's face. The temperature in the room, sauna hot. Ãvike turned to the clock. Fifty-five minutes since the director had barged into her Russian language class. The teacher had seemed shocked by the unexpected intrusion, standing stiffly while the director whispered something into her ear. Ãvike had watched, the tiny hairs at the back of her neck standing on end as the teacher looked suddenly pale.

The director had made a similar visit the week before. That day, he'd also whispered something to the teacher. Then, his hand gripping her elbow, he'd steered the teacher out of the room. Moments later, the director had reappeared, staying to conduct their Russian lessons personally. Several hours later, when the teacher returned, her face had again been ghostly white, except for her red-rimmed eyes. For the rest of the afternoon, she had remained unusually serious and withdrawn, from time to time blotting her eyes.

It was fortuitous, Ãvike had thought. That very morning, she'd come to school with something she knew would cheer her teacher. She could hardly wait until school ended. When it did, Ãvike had lingered, asking for permission to clean the chalkboard and erasers. Her real intent was to present the cheer-maker she'd brought: a drawing.

The teacher had loved the first one Ãvike had given herâHungary's esteemed patriot, Louis Kossuth standing on a pedestal, pointing toward a brighter future. Ãvike sketched from memory, a likeness of the statue she'd seen countless times in her mother's treasured book that told his story. How he led the 1848 revolt against the country's then-oppressors, the German Hapsburgs. These days, under the Russian Stalin Communist dictatorship, the bookâany book about Hungarian historyâwas

tilos,

forbidden. So her mother read from it in the cellar of their apartment building after putting out the lights upstairs.

“Oh, Ãvike,” her teacher had said. “He looks exactly like our Kossuth. You are a gifted artist.” And then she'd kissed Ãvike on her head.

The affection embarrassed her. She remembered how her face had burned, but the tender act had also made Ãvike feel strangely good inside. A pleasant sensation. She craved more of it.

The hint of lavender from the teacher's skin as she pulled away still lingered in Ãvike's memory. “But you must be careful showing such drawings in publicâeven in the privacy of the classroomâthe director would not be pleased.”

So this time, Ãvike knew to be careful, using the guise of blackboard duty to discreetly hand off her latest drawing. Nothing overtly tied to Hungarian history, just a powerful horse. She'd modeled it after one of the seven magnificent steeds bearing the Magyar Chiefs who conquered the Carpathian Basin and founded Hungary in the 9th century. The representations were part of the statue collection in Heros' Square honoring outstanding figures of Hungarian history. Without its rider, her horse would not have obvious historical significance, right?

Then the shock. Before Ãvike had completely unrolled the small paper she had kept hidden under her clothing, the teacher said, “I told you, no pictures. No more drawing.” Her voice was icy. Mean.

To Ãvike, tears, like her pencils and paper, were a luxury. Still her eyes had formed watery pools, blurring the scene of her teacher ripping into shreds the prized piece of paper containing her lovingly crafted work. “Menj el, go,” the teacher had demanded, dismissing Ãvike without another word.

It was only laterâafter a classmate repeated a rumor that the teacher had been found with a contraband drawingâthat Ãvike connected the Kossuth drawing to the teacher's removal from the classroom and, upon her return, the totally changed demeanor. Maybe she should have felt sorry, but she didn't. The sting of her teacher's coldhearted rejection was still too great.

Ãvike had expected to be reprimanded by higher-ups as well, but until fifty-five minutes ago, nothing. Then, “Ãvike!” The director's voice calling her name had sliced through the cone of silence that descended on the classroom when he'd entered.

Her knees felt weak when she'd stood. As she was escorted past her teacher, she tried to catch her eye, receive the telepathic message she wished would be there: “Don't worry,

édes

, you will be fine.” Instead she saw tears streaming down her teacher's face. Ãvike's heart had dropped to her stomach.

Now, nearly an hour into her interrogation, a light coat of perspiration covered every inch of her, as though she had just stepped from the shower. And so far nothing about her drawing, her teacherâ¦only questions about her parents, her mother.

Only!

Ãvike could not ignore the gnawing fear she felt for her mother. But wouldn't she be proud to know that her daughter had not so much as moved a finger to wipe the sweat away? “They could not break me, Mother. I told them nothing.”

Ãvike shifted, peeling her moist thighs from the wooden seat, tugging her blouse away from her clammy skin, flicking the damp fabric. The movement cooled her ever so slightly; it also made her conscious of her full bladder. She had not used the toilet since before school had begun. Then the numerous glasses of water poured by the majorâ¦

The door opened. Major Dumpling entered. In one hand, she held a photograph; in the other was a paper bag. She slid the photographâactually two, one on top of the otherâonto the desk, near the girl. The intense bulb, still trained directly at Ãvike, also cast light on the photo. Ãvike strained to see the image, but it was just beyond her line of vision. Tones of gray on glossy paper.

What did the photographs hold? What was Dumpling up to?

Ãvike breathed deep, a trick she'd practiced with her mother. “It will help you to remain calm.”

The major rattled the bag, spilled its contents onto the empty desk surface. Walnuts. A nutcracker and pick appeared next. Still, the major said nothing. Instead, she cracked nut after nut until a parade of meaty walnut halves formed a column along the length of the photograph.

The terror inside Ãvike swelled. The urge to urinate was also more and more insistent. Long minutes passed, the only sound the cracking of shells. Ãvike, inconspicuously as possible, began to squirm.

“I need to visit the toilet.” Her voice sounded composed. “May I?”

The major leaned forward. “Did you say something?”

Ãvike's bladder ached. “I need to go⦔

“Go? Ah, yes. Go. Go to another meeting with your mother? Distribute subversive materials?” The major lifted the pick. She gestured with it to the photograph. “Pick it up.”

Ãvike reached, felt a hot spurt.

The imageâ¦Her mother at the meeting the other evening! Ãvike had not been paying close attention because she'd been drawing. But she recognized the classroom where they'd been. And she remembered her mother's heated voice, her demand. Ãvike was struck by how young her mother looked, like an older sister and so beautiful. Even with her mouth open, her features twisted in a fervent expressionâÃvike could almost hear the words againâ“The hammer and sickle of Soviet Russia must go!”

The second image on the desk showed her mother with Juliska, the young student who'd burst into the meeting. The scene flashed before Ãvike's eyes. Juliska, her face shiny with sweat, standing just inside the door, panting, fighting to catch her breath. Before anyone could even react, she had covered her eyes, sobbed into her hands.