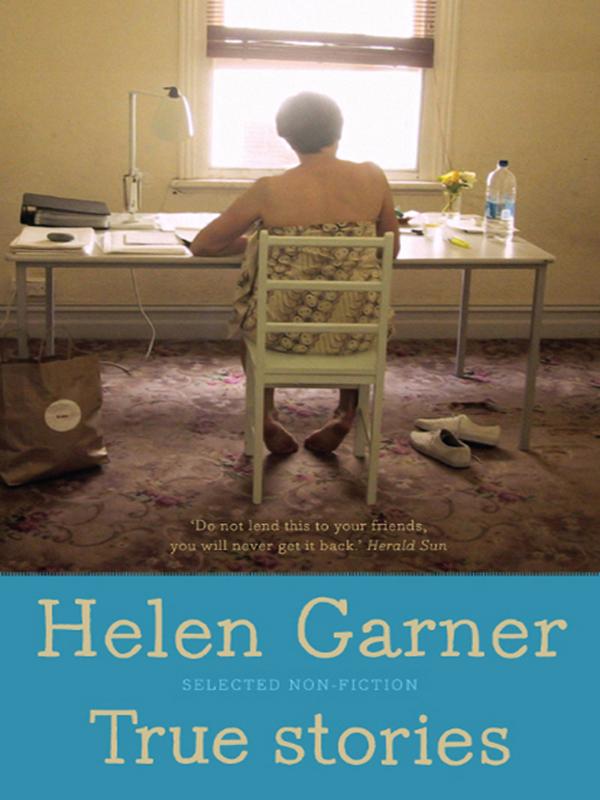

True Stories

True Stories

Helen Garner was born in Geelong in 1942. Her award-winning books include novels, stories, screenplays and works of non-fiction.

The First Stone

, her first work of non-fiction, became an instant bestseller.

Books by Helen Garner

FICTION

Monkey Grip

(1977)

Honour and Other People's Children

(1980)

The Children's Bach

(1984)

Postcards from Surfers

(1985)

Cosmo Cosmolino

(1992)

The Spare Room

(2008)

NON-FICTION

The First Stone

(1995)

True Stories

(1996)

The Feel of Steel

(2001)

Joe Cinque's Consolation

(2004)

FILM SCRIPTS

The Last Days of Chez Nous

(1992)

Two Friends

(1992)

True Stories

Helen Garner

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company Pty Ltd

Swann House

22 William Street Melbourne Victoria 3000

Copyright © Helen Garner 1996

www.textpublishing.com.au

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published 1996 by The Text Publishing Company

This edition published 2008

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

Design by Susan Miller

Typeset by Midland Typesetters Australia

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Garner, Helen, 1942â

True stories : selected non-fiction / Helen Garner.

ISBN: 9781921351846 (pbk.)

Short stories.

Australian essaysâ20th century.

AustraliaâSocial life and customs.

823.3

âA Scrapbook, an Album' first appeared in

Sisters

, ed. Drusilla Modjeska, HarperCollins, 1993, and is reproduced with the permission of the publisher. âThree Acres, More or Less' first appeared in

Gone Bush

, ed. Roger McDonald, Transworld, 1990. âCypresses and Spires' first appeared as the introduction to

The Last Days of Chez Nous & Two

Friends

, McPhee Gribble, 1992. Other pieces in this book, some of them in a different form, first appeared in the

Age

,

Digger

,

Eureka Street

,

Independent Monthly

,

National Times

,

Scripsi

,

Sydney Morning Herald

,

Sydney Papers

,

Sunday Age

,

Time

,

Times on Sunday

, and

Vashti's Voice

.

To Michael Davie

Contents

PART ONE:

A Scrapbook, An Album

Why Does the Women Get All the Pain?

Patrick White: The Artist as Holy Monster

Cypresses and Spires: Writing for Film

Dreams, the Bible and

Cosmo Cosmolino

Germaine Greer and the Menopause

MY WORKING LIFE

has been a series of sideways slides, of adaptations rather than ambitions. It seems to me that I have never actually been trained to do anythingâexcept by one person. When I was nine my parents took me out of Ocean Grove State School, on the south coast of Victoria, and put me into the fifth grade of The Hermitage, an Anglican girls' school in Geelong. There I had a ferocious teacher called Mrs Dunkley. She was thin, with short black hair and hands that trembled. She wore heels and a black suit with a nipped-in waist. She mocked me for my broad accent and my slowness at mental arithmetic. I was so frightened of her that I taught myself to count on my fingers under the desk at lightning speed (a skill I still possess). My mother says I used to scream out Mrs Dunkley's name in my sleep. But Mrs Dunkley also taught grammar and syntax. She drew up meticulous columns on the board and taught us parts of speech, parsing, analysis. She was the person who put into my head a delight in the way English works, and into my hands the tools for the job.

I left school and never saw her again. Naturally, she died. Ten years ago I had a dream about her. In the dream I walked along the verandah off which the Hermitage staffroom opened, and looked in through the glass of the big French doors. I saw Mrs Dunkley moving across the room as if under waterâbut instead of her grim black forties suit, she was dressed in a glorious soft buckskin jacket of many colours. As she moved, colour streamed off her into the air in ribbons and garlands, so that she drew along behind her a dense, smudged rainbow-trail. It's only now, writing this, that I make the connection between Mrs Dunkley and my favourite character in all fiction, namely the Fairy Blackstick in Thackeray's

The Rose and the Ring

, who came to the christening of a certain baby princess and said, over the cradle, âAs for this little lady, the best thing I can wish for her is a

little misfortune.

'

In the mid-sixties, when I crawled out of Melbourne University with a hangover and a very mediocre honours degree in English and French, any dingbat with letters after her name could get a job as a high school teacher. You didn't even need a Dip. Ed., they were so desperate. One summer morning I bowled up to the Education Department in Treasury Place and presented my meagre qualifications to the lady on the front desk. She gave them a cursory glance, and pointed to a large map of Victoria which hung on the wall behind her. âWhat do you want?' she said wearily, âWerribee or Wycheproof?' All I knew about Wycheproof, in north-western Victoria, was that the railway line ran down the middle of the main street. I chose Werribee, thus forfeiting my chance to live and work in the Mallee, the region my father comes from.

My enjoyable but less than brilliant career in teaching lasted, on and off, for about seven years, and ended in ignominy, as one of the stories in this book relates. To this day chalkies of both sexes approach me with a grin in public places and say, âYou owe me a day's pay. I went out on strike for you in 1973.' It was a great stir, and I'm happy about the support but, after wasting a lot of perfectly good time in regret and martyrdom, I was obliged to acknowledge that getting the sack was the best thing that could have happened to me. It forced me to start writing for a living.

I worked forâor, more correctly, I âwas part of the collective that produced'âthe counter-culture magazine the

Digger

for a couple of years in the early seventies. Then I caught hepatitis. I went home and got into bed and stayed there, expertly cared for by my housemates, for weeks. I read

War and Peace.

Somebody brought me the stories of the Russian writer Isaac Babel. When I read, in Lionel Trilling's introduction, that Babel's work had got him offside with the Soviet authorities because âit hinted that one might live in doubt, that one might live by means of a question', I put down the book and howled.

Maybe it was just the gloom that goes with hepatitisâbut more likely it was because till that moment I had never admitted to myself how ill at ease I was, writing for a paper like the

Digger.

(Only one story I wrote for it has made it into this collection.) Things I wrote then felt false to me. I was bluffing. I secretly knew myself to be hopelessly bourgeois.

I was also greatly taken by Babel's statement that âthere is no iron that can enter the human heart with such stupefying effect as a full stop placed at exactly the right point'. This of course was Mrs Dunkley's territory, though I failed to realise it at the time, and though she would not have expressed herself so stylishly. Years later I was reminded that I ought to keep a lid on my passion for punctuation when I bragged to my friend Tim Winton that I had just written âa two-hundred-word paragraph consisting of a single syntactically perfect sentence'. He scorched me with a surfer's stare and said, âI couldn't care

less

about that sort of shit.'

When I got over the hep, I rode my bike down to Silver Top in Rathdowne Street and applied for a taxi licence. But before I could do the test, a communist friend pointed out to me the existence of the Supporting Mother's Benefit and my eligibility for it, as a separated mother of a small child. I applied for one of these instead, and got it. I still regret that I never drove a taxi.

This was the period now loosely referred to as âthe seventies'.

The group

was paramount. In certain circles a person could offend by being âtoo articulate'. But along with all the absorbing collective stuffâdancing and love affairs and communal households and consciousness-raising groups and women's liberation newspapers and Pram Factory shows and demos and dropping acid and mucking around all summer at the Fitzroy Baths with the kidsâI got a fair bit of solitary reading done. At government expense, and don't think I'm not grateful, I launched into Proust, lying on my bed all day by the open window with my head propped on two big pillows and one small hard one, the weighty volume resting upright on my chest.

One day, struggling with a Shakespeare sonnet, I got bogged down in its syntax, and took it across the hall to a bass player who had a science degree he wasn't using. He laid his guitar on the bed and said, âOK. Let's see if we can work it out.' We dismantled the sonnet and pieced it back together. The pleasure of this process was so intense as to be almost excruciating: it felt more illicit than sex. Neither of us ever mentioned it again. More typical of my chosen life at the time was the response I got from a boyfriend when he was sick in bed and, thinking to alleviate his boredom (or my own, now I come to think of it), I said to him, âHeyâhow about we discuss the nature of good and evil?'

âSteady on, Hel!' he said, shrinking back against the pillows.

So I opened my sewing box and mended his shirt instead, while he watched me fondly and played a little tune on his harmonica. In my diary I wrote a song. It went like this.

My charming boy's got a rip in his jacket

I'd take out my needle and thread and attack it

If I wasn't hip to this particular racketâ¦

In those days there weren't many rackets I was hip to, for all the talk. I couldn't even spot my own.

I don't remember ever

planning

to write a novel. There's nothing like having studied literature at university to make you despise your own timid attempts to tell a story on paperâor even to describe people and houses, or write down dialogue. For years you turn on yourself the blowtorch of your tertiary critical training. You die of shame at the thought of showing anyone what you've written. Somebody somewhere says, though, that âthe urge

to preserve

is the basis of all art'. Unaware of this thought, you keep a diary. You keep it not only because it gratifies your urge to sling words around every day with impunity, but because without it you will lose your life: its detail will leak away into the sand and be gone forever.