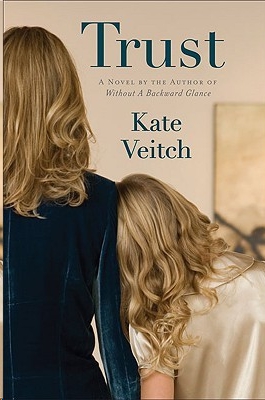

Trust

Trust

Kate Veitch was born in South Australia and grew up in Melbourne. Her bestselling first novel,

Listen

, was also published in Germany, and in the US as

Without a Backward Glance

. She currently divides her time between Australia and San Francisco.

p

R

a

I

se fo

R

kate ve

I

t

CH

’s

L

IS

te

N

‘A compelling drama with a lot of heart and humanity, impossible to put down.’

Australian Women’s Weekly

‘Similar to Anne Tyler in her wry affection for her characters and to Anita Shreve in her aptitude for crafting compulsively readable plotlines, Kate Veitch delivers a remarkably assured debut.’

Booklist

‘A self-assured, moving, hopeful story about the frailties of one – all – families, and the capacity to rage and to forgive.’

The Age

‘A powerful read … Veitch writes with sharp insight into the dynamics of families and the clusters of vulnerabilities, longing and tenderness which define them.’

Adelaide Advertiser

‘A vivid dissection of a fractured family. Veitch has created an enthralling tale of the private sphere.’

Australian Book Review

Trust

Kate Veitch

VIKING

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

BEFORE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

AFTER

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All truths wait in all things,

They neither hasten their own delivery nor resist it,

They do not need the obstetric forceps of the surgeon.

The insignificant is as big to me as any.

What is less or more than a touch?

from Walt Whitman’s ‘Song of Myself’,

found underlined among Clarice Beckett’s papers

ONE

Knees bent, racquet poised, Susanna waited tensely at the net for Gerry, behind her, to bounce the ball his ritual three times. There:

tok! tok! tok!

Yet, for all that she’d steeled herself, still she flinched as the yellow blur whizzed past her right ear. The week before, her husband’s erratic killer serve had thudded into her lower back at top speed; the bruise was still there. No matter if this was just their local club’s B-grade mixed doubles match, Gerry always believed in playing hard.

Joe, receiving, barely reached it in time. His soft return should have been an easy shot for Susanna, but instead she froze, then swiped her racquet ineffectually through the air. Gerry let out an anguished yelp and lunged forward – too late.

‘For god’s sake, Suze,’ he cried. ‘Blind Freddy could’ve got that!’

‘Sorry,’ she said, grimacing. ‘I thought you —’

‘That was

yours

. You’ve got to kill it!’

She frowned at the handle of her racquet and shifted her grip. At least the sun wasn’t in her eyes any more, its light filtered now through the trees that bordered the courts, on the edge of a large park. They switched sides and she crouched at the ready again, trying to look like a serious player.

They lost that game, and Susanna heard her husband suck exasperated breath in sharply through his teeth. Joe’s partner, Wendy, gave her an encouraging smile as they changed ends, and Susanna made a grateful passing comment about the trees, how thin the spring leaf cover was this year. ‘The drought,’ said Wendy succinctly.

Susanna nodded sadly, wondering if the verdant Melbourne she’d grown up in was gone forever. ‘Remember how we always used to moan about the rain?’ But Wendy, ready to play on, didn’t answer.

As Joe prepared to serve, Gerry hissed at Susanna, ‘Remember, he hits topspin, so you’ve got to cut it.’

Cut it?

she wanted to ask.

Remind me how you do that?

Then Joe’s serve came, and seemed manageable, but her return sailed way over the baseline. Instantly her ears were pinned back, alert for Gerry’s admonition.

‘What’d I say? Cut it, cut it!’

‘Not a Grand Slam y’know, Gerry,’ called Wendy across the court. ‘Go easy.’

‘Not to worry, Wen,’ he said, an easy grin in his voice. ‘Susanna likes to get a bit of advice, don’t you Suze?’

‘Absolutely.’ She gave Wendy an airy wave across the net.

As they played on Susanna managed several decent, practical serves, even holding her own in a couple of rallies, but she felt besieged. Joe and Wendy were not just stronger but also more strategic players than her, which as she understood was why their blasting returns were always aimed at her rather than Gerry, who’d taken a step down from A-grade to play doubles with her this year.

Strategy’s just not my strong suit

. Susanna knew that, but it had never been a problem in the years when she’d played with her mother and their friends. They’d laughed a lot; sometimes they lost track of the score, and didn’t even care.

Just do your best

, she told herself.

It’ll be over soon

,

and then you can relax

. Immediately, a voice in her mind shot back:

No you can’t! Remember? The exhibition. The article

. Susanna cringed. Belinda, the head of her department, had been incredibly patient, but she was going to have to come up with the goods. Her job, Belinda had made clear, depended on it, but without a single idea to offer she —

‘Suze!’ Gerry yelled, and she snapped to attention just in time, thankfully, to make a passable shot.

Finally the match ended, and as they walked off the court together Wendy made a point of saying ‘Well done, Susanna.’ Susanna smiled her thanks. She found Wendy a bit intimidating. Nominally, they both taught at the same university, but Wendy was a professor of law with a big office in the heart of the main campus, while Susanna had pottered along for almost fifteen years at an outer-suburban annexe of the visual arts department. Very much the poor cousin.

There were no facilities at these courts, so they’d all left their bags on a bench in the shade. ‘Glass of wine?’ Gerry asked, unzipping the natty black cooler they’d brought. Susanna handed round acrylic glasses while he unscrewed the cap from the bottle, and poured. ‘To the victors,’ he said sportingly, raising his glass in a toast.

‘Cheers!’ Wendy and Joe responded; all took that first welcome sip. The wine was a New Zealand sauvignon blanc, greener than grass, and after the first mouthful Susanna realised that what she needed first was water. Placing her glass carefully at her feet, she glugged half the contents of her refillable water bottle. ‘

Rraah!

’ cawed a nearby raven hoarsely, as though its throat was parched too. She looked up at the big glossy bird, watching her with a beady interrogative eye from his perch on a nearby branch. The tree, like so many in the park, looked like it was on its last gasp.

Joe was raising his glass to Gerry. ‘Well, and here’s to the famous architect. Heard you being interviewed on Radio National the other day. You won some competition in the States, right?’

‘Design for an art gallery extension in Kansas City,’ said Gerry.

‘Yeah, that was it. Fantastic, Gerry!’ Joe clapped him on the shoulder.

‘It’s a pretty big goal for us to kick, all right.’ Gerry flicked back his thick, still-blonde forelock a couple of times with the splayed fingers of one hand, wearing that sweetly serious look that always made Susanna think of Robert Redford. His eyes were just like Redford’s too: the blue of old denim, and twinkling, and irresistible. ‘We’re hoping this’ll really put Visser Kanaley on the map.’

‘As if you’re not already!’ said Joe. ‘What did the bloke on that show call you? Australia’s most innovative architect?’

‘One of,’ Gerry said, with a small self-deprecating gesture. ‘

One of

Australia’s most innovative architectural firms.’

‘Not just Australia,’ said Susanna, taking a half step forward; he rested an arm along the top of her shoulders. ‘Gerry’s concept of interstitial development is getting serious attention in Europe, too, as well as —’

‘Connective interstitial envelopment,’ he corrected, and gave a modest shrug. ‘My little niche.’

‘Connective interstitial envelopment,’ repeated Wendy, slowly, as though weighing each syllable. ‘What exactly does that

mean

?’

‘Briefly? Utilising existing buildings and the spaces between and adjacent to them to extend their use and function,’ said Gerry helpfully, and Susanna saw him smile as the expression on Wendy’s face changed. ‘Development, in other words, designed to minimise demolition and disruption to services, while maximising existing infrastructure. Cost-effective, and a vast reduction in consumption of resources, and space.’

‘Ah,’ said Wendy.

‘World’ll be beating a path to your door,’ said Joe, and took a swallow of wine. ‘Mark my words.’

‘Actually, I’ve just been asked to deliver a paper on it at a conference in New York, next February.’

‘There you go! Congrats, Gerry.’ Again, Joe raised his glass to him. ‘Love New York.’

Wendy asked, ‘Will you go too, Susanna? Still on holidays in February.’

Susanna shook her head, about to explain that Gerry

worked

at conferences and therefore preferred to attend them, if not with his business partner Marcus, then by himself, but her husband interjected. ‘No holiday for our Suze this summer. She’ll be flat out producing paintings for the solo exhibition she’s got coming up.’

Susanna cast a startled glance up at him, but his height – or her lack of it – made it hard to read his face from this close angle.

‘A solo exhibition! That’s great news, Susanna,’ said Wendy. ‘Where’s it going to be held?’

‘It’s just —’ Susanna began.

‘At Booradalla Council’s new civic centre,’ Gerry said. ‘Award-winning building. Quite a buzz about it.’

‘Oh, yes. That’s out near your college, then?’ Wendy asked Susanna, who nodded. ‘Marvellous, Susanna. You’ll be sure to send us an invitation, won’t you? I don’t think I’ve ever seen your work.’

No one has

, Susanna thought.

Because I haven’t got any

. ‘Oh, it’s not till mid next year. And – well, it’s not exactly New York,’ she said with a laugh.

‘Boy, what I wouldn’t give to be in the States for the election in a few weeks,’ Joe said, and, as they sipped their wine, the conversation turned to Obama’s chances.

‘If America had compulsory voting like us, he’d be home and hosed,’ said Gerry, to a general murmur of agreement. Privately, Susanna was tired of hearing about the American election, but she wasn’t about to say that. It would just make her sound provincial. Glancing down, she noticed that her T-shirt was clinging unflatteringly to her puddingy tum; she pulled it surreptitiously away, hoping the others, all taller and leaner than her, hadn’t noticed. She often found herself feeling like the little teapot, short and stout, but how much could she do about that? It was just her build, like all of the Greenfield women; that, and middle age. Yet Gerry, eight years her senior at fifty-three, seemed barely to have aged since she’d met him.