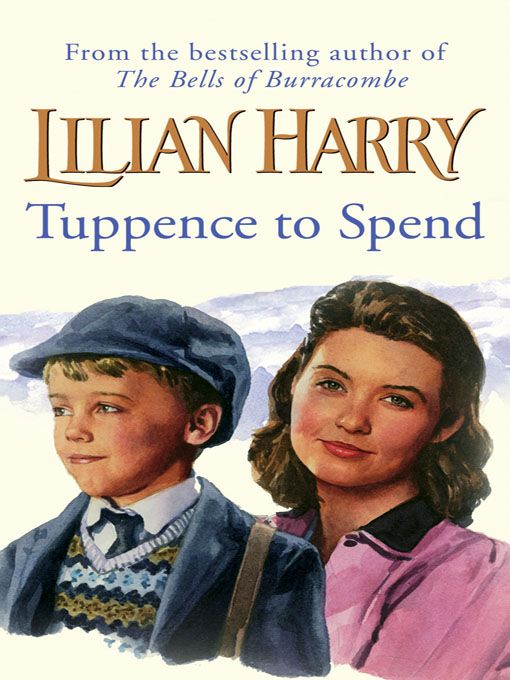

Tuppence To Spend

Authors: Lilian Harry

Ruth had kept Jack’s civilian clothes in the spare-room cupboard. There weren’t many – he’d only needed them when he was home on leave – and she’d never been able to bring herself to throw or even give them away. But now, without hesitation, she went to the cupboard and looked among the clothes folded there. A few blue working shirts, soft from much washing – one of those would do for him in the morning, if she cut it down a bit. And a pair of pyjamas with blue stripes. She took out the jacket and held it against her cheek.

‘I know you wouldn’t mind, Jack,’ she whispered. ‘I know you’d want the poor little mite to have a bit of comfort.’

She stood for a moment with it in her hands, then took it downstairs to where Sammy was sitting, still wrapped in his towel, in front of the fire. Gently, she lifted the towel from his thin shoulders, gave him a few final dabs to make sure he was properly dry and hung the pyjama jacket round his shoulders.

It fitted him like a nightshirt, reaching to below his knees. She looked at him, as thin as a reed, his hair almost white and as soft as a rabbit’s fur, his eyes even larger in a face that, cleansed of its grime, was as pale and smooth as ivory, and her heart seemed to move in her breast.

‘You poor little soul,’ she said, gathering him gently in her arms. ‘You poor, dear little soul …’

Lilian Harry’s grandfather hailed from Devon and Lilian always longed to return to her roots, so moving from Hampshire to a small Dartmoor town in her early twenties was a dream come true. She quickly absorbed herself in local life, learning the fascinating folklore and history of the moors, joining the church bellringers and a country dance club, and meeting people who are still are friends today. Although she later moved north, living first in Herefordshire and then in the Lake District, she returned in the 1990s and now lives on the edge of the moor with her two ginger cats. She is still an active bellringer and member of the local drama group, and loves to walk on the moors. She has one son and one daughter. Her latest novel in hardback.

A Stranger in Burracombe

, is also available from Orion. Visit her website at

www.lilianharry.co.uk

.

The Bells of Burracombe

Three Little Ships

A Farthing Will Do

Dance Little Lady

Under the Apple Tree

A Promise to Keep

A Girl Called Thursday

Tuppence to Spend

PS I Love You

Kiss the Girls Goodbye

Corner House Girls

Keep Smiling Through

Wives & Sweethearts

Love & Laughter

Moonlight & Lovesongs

The Girls They Left Behind

Goodbye Sweetheart

LILIAN HARRY

AN ORION EBOOK

First published in Great Britain in 2003 by Orion

This ebook first published in 2010 by Orion Books

Copyright © Lilian Harry 2003

The moral right of Lilian Harry to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor to be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All the characters in this book are fictitious,

and any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 4091 3035 2

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper Saint Martin’s Lane

London WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

For my lovely granddaughter

Samantha Anne – our own Sammy

Chapter One

‘They’re sending you all away?’ Nora Hodges said, staring at the letter in her hand. ‘They’re sending all you kiddies out of Portsmouth to the country –

this Friday

? But why? I thought they were still trying to make Hitler stop it – I thought they didn’t want there to

be

a war.’

It was almost the end of August. Sammy had been given the letter at school and had almost forgotten about it, but his teacher had said that the letters must be given to the children’s mothers the minute they got home, so he fished it out of his pocket and handed it over, grubby, crumpled and sticky from a half-sucked bull’s-eye Tim Budd had given him in class. He pulled the sweet off the letter and started to pick off the fluff.

At first Nora had stared at the envelope, her heart sinking. Letters from school usually meant trouble – she’d had plenty of that sort from the school while Gordon was there. Or, more often,

not

there. Playing truant – being cheeky – tormenting little girls by sticking their pigtails into inkwells – and, worse, pinching things from the cloakroom. Gordon was always in trouble of some sort. Sammy hadn’t ever got into that sort of trouble before, but then he was only seven – there was plenty of time for him to follow in his brother’s footsteps.

‘What is it?’ she said. ‘What’ve you done?’

Sammy had picked off most of the fluff and popped the bull’s-eye into his mouth. He sat down on the floor and began to stroke the tabby cat curled up on the mat. ‘I

haven’t done nothing. It’s about the war. We all got one. We’re being sent away.’

‘The

war

?’ Her heart sank further. She’d hoped, tried hard to believe, that it wasn’t going to happen. Even with the Anderson shelters all delivered and standing like grey hillocks in all the back gardens, even with those horrible gas masks being handed out to everyone, even with the blackout and leaflets being dropped through the door almost every day, and men being trained for Air Raid Precautions, even after Sammy’s recall to school for rehearsals for the evacuation – she’d hoped and hoped that it wouldn’t really happen, that Hitler would back away and not invade Poland after all, that Mr Chamberlain would find some way of persuading him. He’d promised, hadn’t he? Peace in our time – that’s what he’d said when he came back from Munich, waving his ‘piece of paper’. Peace in our time.

‘When?’ she asked Sammy now, staring at the piece of paper in her own hand. ‘When are you going?’

Sammy took the bull’s-eye out of his mouth to examine it. He’d sucked off the rest of the fluff and it had reached the red layer now. With another few hard sucks it would turn yellow and then green, before reaching the hard little bit in the middle. ‘Friday,’ he said. ‘We’ve got to have our suitcases packed and go to school at seven o’clock. It says so in the letter. Have I got a suitcase, Mum?’

‘No, of course you haven’t! Where would

we

get the money to buy suitcases? Anyway, we never go anywhere to need them. I don’t know what we’re going to do.’ She looked at the envelope again and began to open it. ‘Oh, Sammy – I don’t want you to go away.’

Sammy got up and came to lean against her. He was small for his age and very like her, with fair hair that curled all over his head and large blue eyes. Gordon was dark and solidly built, like his father. He’d always been a handful, even as a toddler, able to climb almost as soon as

he could walk and into everything – you couldn’t leave him alone for a minute. And as he’d grown up he’d followed his father everywhere, wanting nothing more than to do the things Dan did – going to football matches to see Pompey play at Fratton Park, working on the ships at Vosper’s, or at Camber dock. He hated school from the very first day, and made everyone’s life a misery until he finally reached his fourteenth birthday and left school to go to work at Camber.

But Sammy had been much more his mother’s boy, content to be with her. Gordon sneered and called him a cissy, and Dan said the boy needed toughening up, but for once Nora took no notice of her husband. Sammy had come after three miscarriages, and it had been touch and go whether he’d survive, he’d been so tiny, but she’d tended him through those early weeks, keeping him literally wrapped in cottonwool, and now, even though he was still small he was strong enough and there was a bond between them that would never break. And just because he was close to her and had fair curls and big blue eyes didn’t mean he was a cissy, she told Dan. Sammy was every bit as much a boy as Gordon was – he was just a different kind of boy, that’s all.

‘I don’t want to go away either,’ Sammy said to her. ‘Couldn’t you come too? Some of the mothers are going, I heard Tim Budd say so. His mum’s going.’

‘That’s because she’s got a little baby,’ Nora said, putting her arm round him. ‘Maureen can’t go without her mother, can she? She’s only a few weeks old.’

Sammy looked at her. ‘So if we had a baby you could go as well and we could go together. Couldn’t we have a baby, Mum?’

Nora gave a short laugh. ‘A

baby

! No, Sammy, we couldn’t. It takes nearly a year to get a baby, and—’ Her voice broke suddenly and she rubbed the back of one wrist across her eyes. ‘Well, anyway, we can’t.’ She opened the

envelope at last and pulled out the sheet of paper. ‘Seven o’clock Friday morning … But you don’t

have

to go. It says here, it’s just

advising

that you should.’

‘So can I stop home with you, then?’

‘I’ll talk to your dad about it,’ Nora said, folding up the sheet of paper again. ‘Tonight, when he comes home from work.’ She leant back in her chair, feeling a great wave of tiredness wash over her. The thought of finding Sammy a suitcase, collecting his clothes together and packing it, was almost too much for her.

I’m getting more and more tired these days, she thought. It’s all this talk about the war. It’s upsetting me, it’s upsetting everyone. I just feel I’m crawling through the days, and can’t hardly manage to do all my jobs. Getting the dinner ready’s about all I can do and even that’s a struggle.

Perhaps she would feel a bit better when they’d finally decided whether there was going to be a war or not. Perhaps everyone would feel better then, once they knew what they had to face. But then she thought of the bombing they’d been warned about, the possibility of the Germans invading Britain itself, and a sick fear gripped her body. Almost without realising it, she pulled Sammy against her. I can’t let him go, she thought. I can’t let him go without me, to strangers who wouldn’t understand him and might not be kind to him. I can’t.

‘Lay the table for me, Sammy, there’s a love,’ she said, leaning back in her chair and closing her eyes. ‘Your dad’ll be in soon, wanting his tea, and so will our Gordon. And I’ll have a talk with him later on. I don’t see why you’ve got to go away if you don’t want to, specially when we still don’t know that there’s going to be a war. It might not happen even now.’

Sammy spread the old tablecloth on the battered table in the middle of the room, and got knives and forks out of the sideboard drawer. They’d been brought from the pub

when the family had left it to come to number 2 April Grove, along with a few other bits of furniture. The brewery had claimed a lot of it was theirs, but Dan had had a row with the man who came to oversee the move and told him they had to let the family have beds and tables and chairs, it was the law, and anyway a lot of the stuff had belonged to Nora’s parents and even her grandparents, and if the brewery tried to keep them it would be stealing and he’d go to law about it, see if he wouldn’t … And the man had looked at Dan, towering over him, big and dark and powerful, and backed away. They ought to send my Dan to talk to Hitler, Nora thought, remembering it. He’d soon sort the horrible man out!