Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (14 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘But if the water we are in is infinite …’

‘Infinite, yet co-existent with the infinite universe from which we have come! Two such infinites would interpenetrate themselves. Perhaps we passed through one such overlap – and perhaps the light we can see below is another such. The skies of the Oceanus Australis! Descend to it, and we can emerge once again in our home world!’

Everybody was silent for a while. ‘It sounds – insane,’ Boucher offered, in a tentative voice.

‘I agree,’ said Lebret, expansively. ‘But perhaps it is the truth nonetheless! Monsieur Ghatwala,’ he gestured with his cigarette in the direction of the scientist, who was sitting holding a cup of coffee in both hands, ‘you are scientifically trained. Is anything

I have said incompatible with the dimensions of an infinite geometry.’

Ghatwala looked surprised to be invoked as an authority; but he said, ‘No, no, I suppose not.’

‘So?’ prompted the lieutenant.

‘I offer this only

as

a suggestion,’ said Lebret, stubbing his cigarette out. ‘And as a tribute to the honoured memory of our captain. Of course the final decision must be yours, Lieutenant. We could attempt to retrace our path, and float upwards for many days. Or we could spend a few hours descending towards the light, to determine whether it truly is a more direct route to the surface. If it is not – well then, we have lost only some few hours, and can inflate the tanks and go backwards. But if it

is

! Think only of that!’

There was some desultory discussion of the plausibility of Lebret’s account; and some toing and froing about the best course of action. But with the implacable stubbornness of Cloche removed, Lebret was much better able to manipulate the mood of the group. Besides, as he himself insisted – his request

was

reasonable. After such an epic, impossible descent, what were a few more hundred leagues downward?

It looked for a while as if Boucher were going to put it to the vote. Billiard-Fanon, however, cut across this. ‘The decision must be yours, sir,’ he insisted. ‘There’s no place for voting on a naval vessel!’ Boucher’s authority was fragile enough without inviting the contempt of the men via spurious appeals to democracy.

‘Then,’ said Boucher, sounding flustered, ‘let us go down a little further, and see what these lights

are

. Yes, we shall see if Monsieur Lebret’s bizarre theory is correct. I am willing to spend another day on that mission. But if the lights merely are some form of phosphorescence, then we shall immediately re-fill the tanks and ascend.’

‘It may be,’ suggested Lebret, ‘that the light has something to do with Seaman de Chante’s … disappearance.’

‘He must at least have made it to the ballast tanks,’ was Castor’s opinion. ‘We have functioning vents, at any rate.’

‘But the tanks became functional before he went out,’ said Billiard-Fanon. ‘I believe it was coincidence.’

‘There are many oddities here,’ agreed Boucher. ‘I mean, about

the functioning of the ship, never mind the world outside. When we return,’ – for that seductive idiom of hope had started to percolate into the general conversation aboard the ship – ‘an official investigation will be able clear them up.’

He sat himself tentatively in the captain’s chair. Le Petomain was pilot. Lebret, the two scientists and Billiard-Fanon were at the observation porthole. The remaining crew were at their posts at various places in the craft.

Once again, the

Plongeur

tipped forwards to dive down through the waters.

Down they went.

At first the light was indistinct – a vague, blue glimmer. After two hours it was possible to discern an area of more focused light, away to the left. Lebret suggested Boucher come down to the observation chamber and see for himself.

‘Lieutenant,’ said Lebret. ‘We ought to steer towards where the light is brightest.’

‘Very well,’ agreed Boucher. He passed co-ordinates to Le Petomain, through the speaking tube, and the

Plongeur

reoriented itself in its descent. The brightness swung round to occupy the exact centre of the observation porthole.

‘What

is

it?’ Jhutti asked. ‘It is too localised to be the whole sky.’

‘I do not know what it is,’ said Lebret, looking forward as if hypnotised. ‘But soon we shall find out!’

The colour subtly changed, very slowly. The light was now a slightly greener shade of cyan. Brightness was evident in a wide spread up ahead, but it was now certainly most intense in a circular patch.

‘Might it be a

clump

of phosphorescence?’ asked Jhutti, leaning forward.

‘Or an entrance, as if to a tunnel? A cave mouth through which sunlight is shining?’ suggested Ghatwala.

‘A portal, perhaps,’ said Boucher, with wonder in his voice. ‘Just as you said, Monsieur Lebret. If it is some manner of gateway, how can we determine whether it is safe to pass through it? Where will it take us?’

Lebret was silent, staring intently at the brightness below them.

Slowly the descent continued. Another forty thousand metres rolled past on the depth gauge. Boucher returned to the bridge; went aft to check on the engines, and finally returned to the observation porthole. Lebret, the scientists and Billiard-Fanon were all gazing at the slowly strengthening light, as if rapt.

‘I have read accounts of people at the moment of death,’ said Lebret, as Boucher took a seat beside him, ‘in which they talk of a circle of light, hypnotising them and compelling them to move towards it. Do you think this such a phenomenon?’

‘Are we not yet dead, then, Monsieur?’ Boucher asked, trying to humour but sounding only strained and anxious.

Everybody was silent for a while.

‘What gives it that

colour

?’ asked Ghatwala. The light was now a deep glaucous-blue, magenta tinged with green.

‘Algae?’ suggested Jhutti. ‘If we are approaching a source of sunlight then we might also expect to encounter manifestations of life. Blue-green krill, seaweed, anything that can make use of the energy of the light.’

‘And perhaps fish,’ agreed Ghatwala, ‘that feed upon the vegetation.’

They sank deeper through that mysterious sea. The light strengthened. It was evident now that a central circle, or sphere, was the source of the light.

‘The sonar!’ announced Le Petomain, excitedly. ‘At last – it is returning something – an image.’

‘I thought you said it was broken?’ said Boucher. ‘No matter – that’s excellent news! What does it report?’

‘Lieutenant, it’s a—it’s a

dome

. Or perhaps it is the prow of something. Something enormous. And there’s a lot of noise, perhaps a fleet of little craft – or a shoal of fish, I think.’

‘The prow?’ repeated Boucher. ‘You mean – another vessel?’

‘Look!’ exclaimed Lebret. ‘There

are

things moving!’

Everybody strained forward. Tiny rice grain-shaped objects, dark blue against the light,

were

swirling around the source. ‘Exactly as I said!’ said Ghatwala. ‘Fish!’

‘Monsieur Lebret,’ said Boucher. ‘I must congratulate you on your intimation! Surely we are approaching the surface, howsoever unconventionally … for surely fish cannot shoal like this in the deep depths, but only at the surface.’

‘The surface,’ agreed Lebret. ‘Or

a

surface.’

‘Lieutenant?’ It was Le Petomain’s voice, reedy through the communication pipe. ‘The external temperature has risen quite markedly.’

‘Getting warmer!’ said Boucher. He looked pleased. ‘It all makes a sense. Except only that we are apparently

de

scending, when we ought to be

a

scending, it makes sense! The pressure increased when we went sank through the Atlantic; it reduced again as we passed into this mirror ocean. The temperature went down, now it comes back up. It got darker, now it gets lighter. It can only mean we

are

returning!’

‘Praise the Lord!’ cried Billiard-Fanon.

The more they descended, the larger and brighter everything was. The circle of blue-green brightness was now, very obviously, a distinct thing, the cause of, but differentiated from, the more diffuse brightness all around them. The indistinct shapes of the swimming creatures – whatever they were – began to acquire definition – more like octopi than ordinary fish, for they trailed tentacles behind them as they moved.

‘It’s warm,’ observed Jhutti. The air inside the observation chamber was palpably hotter.

‘It is,’ agreed Boucher. He picked up the communication pipe. ‘Le Petomain?’

‘Lieutenant?’

‘What is the external temperature reading?’

‘37°, Lieutenant.’

‘What? How can it be so high? A few hours ago it was 4°C!’

‘I’m sorry, Lieutenant Boucher,’ replied the pilot. ‘I must report it is 37°.’

‘Something is wrong,’ said Jhutti. ‘That is much too hot.’

‘I am unpleasantly reminded,’ put in Billiard-Fanon, in a gruff voice, ‘of the story of the frog placed in cold water which is slowly

heated up. The frog,’ he added, perhaps superfluously, ‘fooled by the slow increments of temperature increase, and not realising his danger, does not leap from the pot, and so dies.’

‘How can it

be

so hot?’ Boucher repeated.

‘Le Petomain,’ said the lieutenant, speaking into the tube. ‘What do the instruments say? How can it be so hot, suddenly?’

‘I don’t know, Lieutenant.’

‘What about the sonar?’

‘Something is jutting out, the source of the light and the heat. But there are so many of these strange fish swimming about it is interfering with the signal. Too much noise.’

‘Jutting out

, you say?’ asked Boucher.

‘Yes, Lieutenant.’

‘Like the peak of an undersea volcano? That would explain both the heat and light.’

‘It would be consistent with the data,’ said Jhutti, in a grave voice. ‘What if we

are

finally approaching the bottom of this impossible ocean?’ He scratched his beard. ‘I can’t explain the lack of pressure – but what if we are looking at some kind of volcanic eruption through the ocean bed? It would explain how there is light

and

heat at this great depth.’

Lebret shook his head. ‘Monsieur, consider the colour! Observe it! Magma would surely be red!’

‘I cannot explain the colour,’ conceded Jhutti.

‘No, no,’ said Boucher, fretfully. ‘We cannot risk getting closer.’

Disappointment was palpable. The prospect of a quick passage back to normality had possessed everyone; to have that suddenly snatched away lowered morale.

‘We simply cannot descend any further, given the increase in temperature,’ Boucher said. ‘To go lower would be to cook ourselves. And besides, if the seabed is approaching, we must avoid a collision. Time to go back

up

, I think.’ He gave the order, and the

Plongeur

stopped descending.

Not even Lebret challenged this. The two scientists begged an hour to observe what they could of the peculiar phenomenon, and it was agreed that a short period would be given over to the

collection of whatever scientific data could be gleaned from the circumstance.

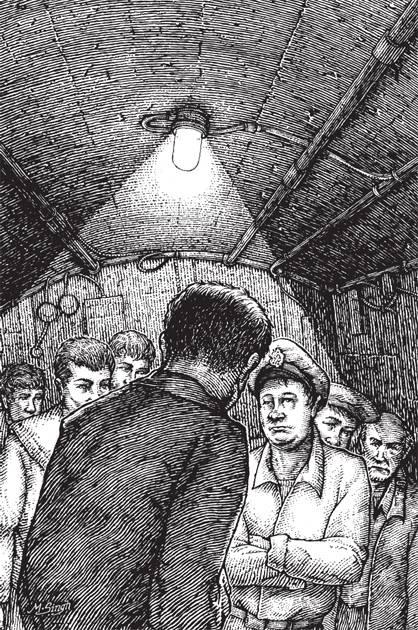

Jhutti and Ghatwala had left their camera down in the observation window. They went back down; and Boucher angled the submarine in the water so as to bring the light source – whatever it might be – into better view. In ones and twos the whole crew came down to take a look for themselves. Lebret, smoking, scowled through the glass.

‘Another crack in the seabed, perhaps, Monsieur?’ Jhutti suggested, to him. ‘A circular vent, through which is pouring … what?’

‘It cannot be lava,’ was all Lebret would say.

‘But,’ Jhutti pressed. ‘The lieutenant is surely right to be cautious. If the external temperature became too high, it might provoke further malfunction …’

‘Look!’ Lebret interrupted him. ‘We have, at any rate, attracted the attention of the local fish.’

It was true – a number of the creatures had broken off from their circling trajectories around the light, and were coming towards the

Plongeur

. As they approached their shape became easier to make out. Crewmen crowded into the observation chamber to look at them.