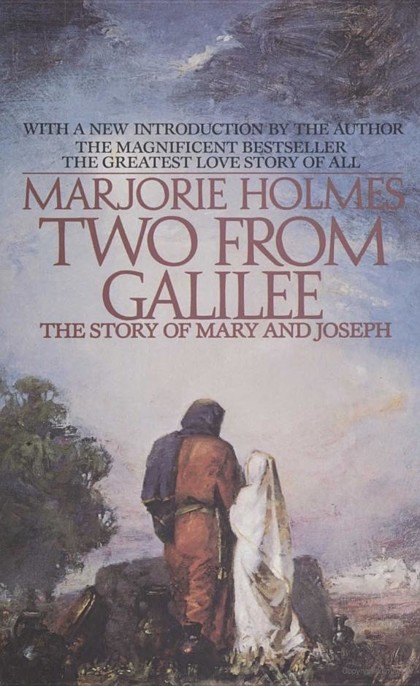

Two from Galilee

Authors: Marjorie Holmes

TWO FROM GALILEE

A Love Story

Marjorie Holmes

GUIDEPOSTS ASSOCIATES, INC.

Carmel, New York

Copyright © 1972 by Marjorie Holmes Mighell

Published by Fleming H. Revell Company

All Rights Reserved

Guideposts edition published by arrangement with Fleming H. Revell Company

Printed in the United States of America

To

Ruth Aley

AND now she was a woman.

She was a woman like other women and her step was light as she hurried through the bright new morning toward the well. She knew she need not tell the others, they would know the minute they saw her. They would read her secret in her proudly shining eyes. And she knew she need not tell her beloved (if indeed he was still her beloved) though to speak of it would have been unthinkable anyway. He too would know. If, pray heaven, there were some way to see him before this day was past.

She must arrange it somehow . . .

would

arrange it somehow. Anxiety mingled briefly with her joy, yet her resolve was firm. Her parents would be shocked if they suspected—she was a little shocked herself. But somehow, some way, before this day was over she would see Joseph. Make him realize that at last she too was eligible to be betrothed. To be married.

For she was a woman now.

In the doorway, Hannah pulled back the heavy drapery which smelled musty from the long rains, and watched her daughter go. Her eyes yearned after the small lithe figure in the blowing cloak, balancing the jug upon her head almost gaily, despite the dragging pain that even Mary could not deny. "Let Salome go in your place," Hannah had offered, to spare her. But Mary had been insistent. "Of course not, she's younger. It's Jahveh's way with women, that's all. And all the more reason I should carry the water. I'm a woman now!"

"How long can I keep her?" Hannah grieved, watching her first-born disappear at the bottom of the windy hill. "How long will it be? Surely the Lord gave me the comeliest girl in Nazareth." She turned back into the house with a proud if baffled sigh. "Never did boys regard me with such longing as boys have regarded Mary from the time she first ran playing in the streets. Never did my own mother look thus upon me."

Mary was well past thirteen. Fortunately, her coming had been late. Something clanged harshly in Hannah. She herself had been barely twelve when given to the vigorous Joachim in marriage. . . . But no, she would not dwell on that. He had proved a wonderful husband in the end, and if possible he loved this exquisite daughter even more than she did. He would not be pressured into a betrothal even now; he would save Mary for the proper suitor. Sentimentalist though he was beneath that gruff exterior, Joachim would never yield to foolish pleas. When they gave over their Mary it must be to someone both rich and wise, someone truly worthy of so exceptional a bride.

The sun was fully up now, its pink light softening the objects in the rude, small room—the low table with its benches piled with cushions, the chest, the cold unkindled oven. She had better rouse the other children. But Hannah refrained a moment, savoring the thought of them sprawled on their pallets.

Mine,

she thought, and shuddered at the never ending wonder. Yes, even though Esau the eldest son was crippled and would never see the light of day . . . even so . . . out of these loins that were cold and empty so long, suckled at these breasts. . . .

And she pondered Mary's words—"the way of Jahveh with women." So bravely spoken, and so

vulnerable,

somehow. Hannah's breast ached even as she gave a cryptic little laugh. She began to call the children, crisply, that they might not suspect her emotions, and cracked a stick of kindling smartly across her bony knees. The hurt of being a woman—she would draw it into her own body if she could, she would spare her child the whole monstrous business.

But no, not monstrous, she sternly corrected. Simply the Lord's reminder that women were less than men. An afterthought, a rib. And it struck her as wry and startling that he should deign to honor one of them by making her an instrument of his great plan. For it was to be out of a woman that the Messiah would come. A virgin, a young woman. Not carved out of noble new-made clay like Adam, ready to smite the accursed Romans and bring Israel to her promised glory. Not flung like a thunderbolt from an almighty hand. No—as a squalling baby, the prophets said.

Out of one of these selfsame humble, unworthy, bleeding bodies. And thus it was that every Jewish woman cherished her body for all its faults and thought:

Even I could be the one.

Thus it was that mothers looked upon their daughters as their breasts ripened and thought—even she! But not really. No, not really. There lay in Hannah a practical streak as salty, flat and final as the Dead Sea. She was not one to pray overlong or fast and hear the fancied sounds of harps and angelic wings. She was not like her sister Elizabeth whose husband was a priest at the Temple and who consorted with the holy women there. She had Joachim and her five children and for her that was enough. When the time came (and it was near, many thought—after five hundred years of exile and slavery!) it would come, that's all, and have little enough to do with her.

There had been many children in the house of Hannah's father in Bethlehem and they were very poor. Though he was of the priestly line of Aaron, her father's limbs were twisted; and since priests must be perfect of body he was ineligible to serve. He had become, instead, a smith. He always stank of the forge and the fire, yet Hannah adored him, the tart acrid tang of him as she clambered over his dear misshapen limbs.

She was a wild little thing and her favorite memories were of running with her brother Samuel into the hills or along the busy streets. Bethlehem, now there was a town! No bigger than Nazareth, but always something doing. There was a great inn near the city gates. Its chambers and courtyards teemed with travelers on their way to Hebron and coastal cities to the south, or making a pilgrimage to nearby Jerusalem. Many of them were descendants of David, come to visit his birthplace. All were alien and exciting, drawing a noisy band of color across the provincial little Judean town.

Hannah and Samuel dove in and around their hairy legs like agile rats, feeling the rough bright robes that smelled of sweat and oil and musty spices and the dust of the great highways. They felt a boldness and a sense of special privilege as natives of this ancient cradle of Israel's greatest king. Jerusalem too lent them reflected glory. On clear days, tending goats on the hillside, they caught a glint of its dazzling colonnades, and the haze of its holy smoke paled the skies. You could even catch whiffs of the meals the priests were forever cooking on their altars to feed the vanity of God. The scent made the jaws leak, for meat was scarce in the house of a humble smith.

And then suddenly she was no longer a rowdy scamp running free when she should have been home spinning and learning of womanly things. A bloody hand had smitten her in the night. She hid her horror as best she could for two days, when her mother noticed her unnatural silence, her pallor, and put her mind ironically at rest. It meant only that she must leave off being a child, since she was now herself ready to beget.

The eyes that regarded her were filled with both agitation and tenderness. Their message was clear: "Though heaven knows what manner of man will have you." Then, hopefully, "Our kinsmen from Nazareth will be coming for the Passover Feast. It may be that their son Joachim. . . ."

It was accomplished with almost unseemly haste. Before the year was out she was setting forth with her new husband for the unknown hills of Galilee. "Whither thou goest I will go. . . ." The words of Ruth throbbed with new significance. Hannah turned wet eyes for one last look at Bethlehem, then put her small trembling hand into the big rough sheltering one of Joachim.

Joachim—huge, ruddy, leonine, with his thatch of dry red hair. Saying little, either from shyness or reserve, and when he did speak, in a countrified accent. Yet a man with a queer dignity about him, and the look of deep and secret ponderings in his eyes. The look too of some recent pain. She was mad to know him completely, hurl all her energies upon him, possess him, love him.

Yet the shock of the marriage bed had been an evil dream. An evil dream all of it—the interminable journey to Nazareth, and having to live with Joachim's mother in the home of his older brother. Hannah had fallen ill, and when after many months she did recover, her womb was as frozen ground. If Joachim hadn't been a man of immense patience and devotion he would have divorced her. But bravely he had endured the disgrace of a wife who remained barren while all his sisters bred. He suffered no word to be spoken against her by his mother, who was certainly no Naomi (but then Hannah was no docile, doting Ruth). He even helped her with the water pots sometimes and brought her such small gifts as he could afford from the marketplace.

Why then she had often berated herself—why was it that she could scarcely bear his touch? For she had come to know what a wretched thing she was. And that for the first time she was completely loved.

At length Joachim's mother had died and the few acres they had tilled together belonged to his brother Simon. At first it seemed a hard thing, moving to this smaller mud brick house and striving to live on what Joachim could earn as a laborer until he could buy a little plot of his own. Actually, it had opened the sluice gates to happiness. Oh, the blessed silence after the clacking tongues. The joy of being mistress of your own house, however rude.

The house stood on the crest of a hill, commanding a view of the rich green pasture lands and orchards that made Nazareth the flower of all Galilee, as people claimed, even though it was but an insignificant hamlet, cut off from the main trade routes. Now, as she was slowly waking to herself as a woman Hannah wakened to the beauty of this place. The surrounding hills shimmered with the gold and bronze of grain in season, the purple-green tones of the vineyards, the silver of olive groves. White clouds coasted across the face of Mount Gilboa, trailing their ships of shadow. To the east lay the shining Mediterranean, and even nearer to the west, beyond Mount Tabor, the lovely flashing lake of Galilee.

One day Hannah stood in the doorway gazing upon all this handiwork of God. To her surprise, for it was midafternoon, she saw Joachim toiling up the steep path toward her, a young kid struggling in his arms. It was the first offspring of their she-goat which he had left off work to show her. And suddenly the sight of him, sunburned and sweaty, with the young thing bobbing against his chest, was as if all the heat of heaven had focused upon the chilled locks of her heart. Her breath came fast. And whereas she had been wont to gaze upon him boldly, without expression, now she lowered her eyes and wept.

"Hannah, what is it, are you ill?" her husband cried.

She shook her head but she could not stop weeping. She wept for all the lost years of unhappiness behind them and for the happiness to come. She wept for love.

Now came rapture, slow, insistent, tracking her down. Now a veritable explosion of rejoicing so violent it was like a pain. The sober, tough little face set in its patterns of defensive rejection began to break, unfold. She caught herself smiling as she worked; she sang. She felt lean and free and newborn; she stretched, she yearned, she gave. And then the miracle. It was discovered that Jahveh had at last blessed her womb.

Hannah bore a daughter, almost too beautiful to believe. They called her Mary. Despite the fact that she had failed to bring forth a son, friends and relatives came to rejoice with them, and the couple were beside themselves with pride. Hannah particularly. Joachim's happiness was tempered by his sense of obligation. It seemed to him that this child had been a direct answer to prayer, and as such must belong to God.

He pondered long in silence. But when it was time for his wife's purification he spoke to Hannah even as she wrapped the baby in the shawl. "When she is five years old it might be well to take her to Jerusalem and present her to the priests."

Hannah turned her back on him, appalled. "We have saved the redemption fee," she said. "Surely the Lord will be satisfied."