Two Moons (3 page)

Authors: Thomas Mallon

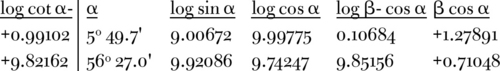

Exercise in 5-Place Logarithms. From the following values of log cot α find α (to the nearest tenth of a minute), and then log sin α, log cos α, log

β

cos

α

and

β

cos

α

. log

β =

0.10909. The algebraic signs in the first column are those of the cotangents themselves.

Cynthia’s last look around before beginning revealed a now fretful Mr. Gilworth of Johnstown, Pa. Could he really be finding this exercise so difficult? She set about filling in the table, sprinkling the numbers like raisins into a cupcake tin. It was more soothing than sewing, and less of a strain on the eye.

Her columns grew longer, and if she squinted at them, the confetti of inkings began to resemble a skyful of stars. She had time to let her mind wander. The Magi’s search for Bethlehem; the music of Milton’s crystal spheres; the prognostications of the D Street astrologer in whose parlor Cynthia had lately spent a dollar she could not afford: they could all be reduced to these numbers. There was actually no need to squint and pretend that the digits were the stars. They were, by themselves, wildly alive, fact and symbol of the vast, cool distances in which one located the light of different worlds.

She knew, from some long-ago visits here with her father and mother—a free weeknight amusement—that the Transit Circle, through which the men see stars cross the meridian, lay just beyond the walls of this room. The astronomers look up and watch the stars come in and out of their line of sight, and as the night wears on and the men grow tired—she is sure of this, so strongly has she imagined it—they have to feel it is not the axis of the earth, but the stars themselves that move.

Parallax

—she had recited the definition several times while she lay in bed studying this week—“the apparent change in the position of an object caused by a change in the viewing position of the observer.” What a comforting delusion, what an exaltation, when the object is a star, and the “viewing position” this Earth no God would choose for the center of His universe.

As her columns lengthened and she went on to problems no. 2 and 3, she heard schoolchildren shuffling through the hall outside. Elsewhere pieces of equipment were being wheeled and crated. Here in the library the astronomers came and went in quiet, disputatious pairs—the older ones wearing full beards, the younger just muttonchops or a mustache—to fetch down a volume and settle a point. And yet, all this activity was only preparation or postscript. This was a theater, and what counted could not happen until night fell.

Mr. Gilworth was left-handed, and he attracted Cynthia’s attention when his numerical jottings, so much slower than her own, gave way to a fast cursive movement. Added to the distressed expression on his face, it could mean only one thing: he had thrown in the towel and was writing a note to the examiner, like the wretched pupil he had no doubt always been back in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. A moment later, on his feet and trying to salvage some dignity, he put a small sour grape into her ear. “You know the dead admiral?” he whispered. “The elder Davis? Don’t believe what you read in the

Star.

It was malaria that killed him. And you know where he got it.” He pointed straight down, meaning “right here,” though nothing could feel more salubrious than the unaccountably cool confines of this hushed library. “Take care of yourself,” he said.

She gave him the smallest of smiles as he retreated, leaving his half-done exam on the farthermost desk. If he didn’t go home to Pennsylvania, she decided, Mr. Gilworth had a great future. He was in a city that would always require men who can change what they want on an expedient dime.

She was finished, and hoping they’d notice how she’d done the whole thing in ink, without one cross-out. Should she open Hawthorne’s life of Pierce? Or would that be too showy a way of idling out the time remaining, during which “b. 1855,” she could see, was still slowly, and in pencil, proceeding with what she wagered was only problem no. 2.

They are going to pick me. A week from now, instead of trudging up the stone steps of the Patent Building and into the Interior Department, I shall be coming here each morning to calculate the men’s infinite gazings upon the night before. Yes, Professor Allison—he had come back into the room for the first time—you are going to pick me.

Right now he stood over “b. 1855,” looking at her paper—without interest, Cynthia judged; not displeased, but certainly not impressed, either. She looked back down at her own work. No, whatever the girl was still doing, it wasn’t going to be good enough; not as good as what she herself had already accomplished without a flaw. And would accomplish every day, just as perfectly, in dresses more colorful than the ones on the hook back in her room. Surely, their eyes having been fixed on the stars all night, the navy men here, come daylight, would not mind a rustling of bright fabric, however old its female wearer.

He approached, reentering her field of vision, crossing

her

meridian, the polished centermost floorboard in front of her desk. He looked at her paper, upside down, his head bowed low over it, to compensate for his vantage point. And when he raised his head, his face, flushed and smiling, rose up like the sun.

“Cynthia May,” he said, pointing to the name she had obediently inscribed upon each sheet.

“Yes,” she replied, looking into his eyes. “Like Mary Jane.”

“I’ll cut your tongue out!” cried Mary Costello. She scooped up Ra, the yellow tabby who had his paw in the cream and looked as if he might splash a drop or two on her silk wrapper or—worse yet, sweet Jaysus!—the chart she was preparing for the man himself. “Away with you, now,” she murmured, kissing the old cat and placing him in a patch of sun on the windowsill above her hand-painted sign: “Madam Costello, Disciple of Mlle. Lenormand, Paris.

PLANET READER

.” It was a big day here at the corner of Third and D Streets. “Mustn’t make a mess,” she cautioned Ra, making her way back to the consulting table. “Not with our magnificent Scorpion coming.”

The senator, as he’d told her on his single previous visit, had a birthdate of October 30, 1829, seven days into his Sun sign, which, according to Master Gabriel’s

Gospel of the Stars,

open next to the teapot, made him and those similarly born “full of courage and anger and much given to flattery. Many promises will they make and little will they perform. After the serpent’s fashion they will beguile those who trust them and with smiling faces will lure their enemies to destruction.”

“Well!” laughed Mary Costello. “We can’t go telling him

that,

can we, pussums?” Unworried by Master Gabriel’s dire trumpetings, she poured herself another cup of tea. The sky, thank heavens, held as many explanations as it did stars. Whatever the Sun failed to yield, the moon could supply; what the monthly cycles would deny you, the hourly ones might provide. Born at noon, or close to it, the senator could safely be promised measures of fame and prosperity even greater than those he already enjoyed.

Did she have time to peruse one of Master Gabriel’s competitors before he arrived? She consulted the clock on the mantelpiece. It always ran behind, and for a moment she wished she might live nearer the river, close enough to see the ball drop at noon. Clients had a right to expect a certain

precision,

and a clock such as hers, unable to keep

up with Earth’s movement through the heavens, must surely fail to inspire confidence. She draped a scarf over it, hiding the face if not the ticking, and went back to her books and her chart-in-progress. Her predictions for the senator’s absent wife, home in Utica, and for his mistress in her mansion above the city, were phrased so politely they would sound more like inquiries after the health of family members than nuggets of celestial information designed to manage his movements between the women.

“I shall never keep all the politics in my head, ain’t that so, Ra?” If the senator did become a real client, she would have to take the

Star

regularly, not buy it every third or fourth day and put it into the canary’s cage half-read. She had trouble enough keeping straight what she actually knew of the sun, moon, and stars; how would she manage the long list of the senator’s enemies and concerns?

Well, this wouldn’t be the first load Mary Costello had hoisted in her forty-seven years; and she was a much quicker study of earthly mortals than the spheres that swirled around them. Ten minutes after he’d pulled her doorbell on Sunday night, a complete surprise, she had a pretty good idea as to why the senator had come to seek her out. He was, he’d told her, responsible for the President due to be enthroned the following morning. Having more or less created the commission that settled the mad, disputed election in favor of Governor Hayes, he stood as the Prime Mover, the hand that had flung the Sun into position. And yet, she could tell that this knowledge had left him, maybe for the first time in his life, afraid and resentful. Having failed to become the Sun himself (what he really craved), and newly aware of those seeking to banish him where no light shone at all, the senator had reached a secret crisis in his fortunes and confidence. So he had come to her in the night, looking over his well-muscled shoulder, dressed in his magnificent clothes and face and voice, this gorgeous brute requiring whatever reassurance she could call down from the stars.

She looked around for her turban—not a piece of professional

paraphernalia, just something she used to hide her thinning hair. “Now, don’t I look

lovely,

pussums?” She laughed at herself in the mirror, before taking the window seat below Ra’s sill. Together they looked out onto the street, toward the people getting down from the trolley: the women, sweating in their velvet; the anxious, office-seeking men, moving between their hotels and whichever new Cabinet Secretary they’d be calling on next. She usually welcomed drop-ins, but the senator had instructed her to keep the decks clear this afternoon, and she had hung a “by appointment only” shingle beneath the placard invoking Mlle. Lenormand.

She hoped he wouldn’t ask for a complete horoscope, at least not yet. Only with great difficulty—using lima beans to calculate, when she ran out of fingers—had she located the moon’s position in his Sun sign. Numbers and history had never been her suit. When told, ten years ago, back in Chicago, that the twelve signs of the Zodiac matched up to the twelve tribes of Israel, she’d asked Iris Cummings just who these twelve tribes were, and how come they hadn’t turned into a baker’s dozen under the hot desert sun.

Looking over the windowsill and down at her sign, Mary Costello realized that these days she sometimes thought she

had

been a pupil of Mlle. Lenormand’s, and that Mlle. Lenormand really was a famous Parisian planet reader instead of a name she’d found on the label inside a hat at Cooley & Wardsworth’s. If the truth be told (but who had to tell it?), it was Iris Cummings who’d taught her the stars. Iris, the smallest girl at Madame Lou Harper’s establishment on Monroe Street, but smart as could be; could talk about Venus and Jupiter by the hour whenever she came into the Hankinses’ gambling house, where Mary Costello in those days wiped tables. Al and George had loved superstition; behind the bar, amidst the pinochle decks, there was always a pack of tarot cards, and they craved hearing little Iris go on about all the mysteries that only

seem

beyond our reckoning. Mary had started making notes, first inside her head and then on a tablet she kept in her shack one street behind Hair Trigger Block.

She’d picked up plenty, certainly enough to tell the senator that the moon in Scorpio is an evil thing, and that those born with it require quite a bundle of additional planetary influences to keep from hurting other folk. Yes, she

could

tell him that, but what she’d learned in life—more important than all she’d learned from little Iris or Master Gabriel—would make her keep her trap shut about this unattractive lunar truth. She gave people as much knowledge as they could comfortably stand, and no more.

Candles: lit or unlit? “What do you think, pussums?” Unlit, she decided. The senator sought not hocus-pocus but expertise, a heavenly species of the facts and figures his committees knotted into laws and budgets. Wearing a bracelet or two less wouldn’t hurt, either. She slid one off her wrist just as the doorbell rang. Fluffing her turban, she looked out the window and saw—oh,

bejaysus

!—not the senator at all, but that tiresome girl, that tall bird of an Aries who lived a couple of streets away and had been here a week or so ago. And what for? She mocked the stars’ predictions even as she sought them. Every other female who came up these steps settled for an encouraging word about a lover or a legacy, but this one couldn’t make clear what she was seeking to know. Now, how to get rid of her quickly?