Two Short Novels

Authors: Mulk Raj Anand

Mulk Raj Anand

(1905-2004) was born in Peshawar (now in Pakistan), and educated at the Universities of Punjab and London. He began his career by writing for T. S. Eliot’s

Criterion

and went on to win international fame with his heart-warming portraits of the Indian landscape and its people. With a sensitiveness which is uniquely tender and an imaginative fervour which is contagious, his stories and novels explore little known and not-so-familiar corners of the Indian soul and show the technical virtuosity of a master story-teller.

Author of more than a dozen novels, short stories, and critical writings, Mulk Raj Anand was honoured with Sahitya Akademi Award, the most prestigious and coveted Indian award for literary writing, in 1972. He held the Tagore Chair at the Punjab University and has edited

Marg,

a reputed quarterly devoted to the arts. Recipient of several honorary doctorates and other distinctions, he spent the last years at his picturesque retreat in Khandala, a hill station in the Western Ghats outsite Mumbai.

‘Mulk Raj Anand’s historic importance has already been established... he stands out as a figure of towering humanity whose words guide us through the multitudinous complexity of India with more verve than any other prose writer of his time.’

Alistair Niven in

The Hindu

By the same author

The Hindu View of Art

—

The Lost Child & Other Stories

—

Untouchable

—

Coolie

—

Two Leaves and a Bud

—

The Village

—

Across the Black Waters

—

The Sword and the Sickle

—

Apology for Heroism

—

The Big Heart

—

Seven Summers

—

Private Life of an Indian Prince

—

The Old Woman and the Cow / Gauri

—

Conversations in Bloomsbury

—

Lajwanti & Other Stories

—

Morning Face

—

Confession of a Lover

—

The Bubble

—

The Mulk Raj Anand Omnibus

—

A Pair of Mustachios & Other Stories

—

Man Whose Name Did Not Appear in the Census & Other Stories

—

Things Have a Way of Working Out & Other Stories

—

Selected Short Stories (Penguin)

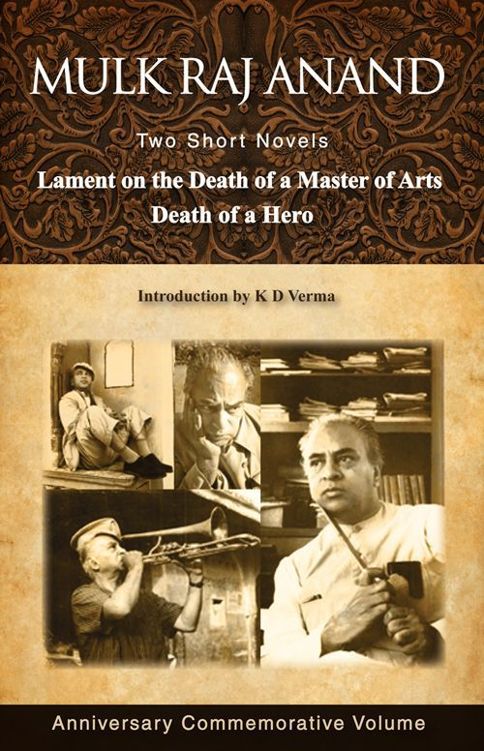

Mulk Raj Anand

Two Short Novels

Lament on the Death of a Master of Arts

Death of a Hero

Anniversary Commemorative Volume

Introduction by

K.D. Verma

Prof., Univ. of Pittsburgh-Johnstown, U.S.A. DELHI | MUMBAI | HYDERABAD

DELHI | MUMBAI | HYDERABAD

www.orientpublishing.com

ISBN : 978-81-222-0515-2

1st Published 2012

Two Short Novels: Lament on the Death of a Master of Arts & Death of a Hero

© Lokayata: Mulk Raj Anand Centre

Cover Design by Vision Studio

Published by

Orient Publishing

(A division of Vision Books Pvt. Ltd.)

5A/8 Ansari Road, New Delhi-110 002

Printed in India at

Saurabh Printers Pvt. Ltd., Noida

Cover Printed at

Ravindra Printing Press, Delhi-110 006

Introduction

S

aros Cowasjee’s laudatory proposal to bring forth a commemorative volume of Mulk Raj Anand’s two short novels,

Lament on the Death of a Master of Arts

and

Death of a Hero

,

on his birthday will undoubtedly help readers to get acquainted with another challenging side of the celebrated author of

Untouchable

and

Coolie

. While

Lament on the Death of a Master of Arts

, first published in 1938, takes us back to the British colonial India of the modernist era of the thirties,

Death of a Hero

brings us face to face with the historical realities of the beginnings of free India. Evidently,

Lament

is a poetic dirge on the philosophies of pain, loss and grief, but

Death

as an epitaph is Anand’s poetic aside on liberty and the function of the poet as reformer and legislator. Undoubtedly,

Lament

could be read as a prose poem on the death of Nur, but in that sense

Death

is also a poetic treatise on the unfortunate death of poet-teacher Maqbool Sherwani. Both these short novels have strong cathartic stratifications that direct the respective heroes to explore the psychological processes of imploding the realities of inner consciousness. Nur’s death in

Lament

is a tragic loss perpetrated by the vitiated structure of society, but Sherwani’s death is a political murder and hence a sacrificial death. Yet it must be noted that despite some of the obvious similarities, the two novels are distinctly different in style, setting and meaning.

The story of Nur’s education, illness and death unfolds a psychosociological process of cathexis and transference, but the story of Maqbool Sherwani is based on direct and fearless action inspired by poetic, moral and political idealism. Yet both the deaths are gruesome and unceremonial crucifixions. Arguably, the two stories must be placed in the larger context of Anand’s ideals of humanism, the world of values and the dignity of fellow man as sharply pronounced in the 1945 Postscript appended to

Apology for Heroism

.

It is important to understand that Anand’s humanism, based on the world of values, is directly focused on the truth of the human condition and that this truth constitutes the basis of the moral and spiritual nature of man’s imagination. In examining such intricate issues as human suffering, human dignity and human values in general, how must one rationalize Nur’s lost dignity and Maqbool Sherwani’s blatant murder? Can Nur ever regain his lost dignity, or must he embrace death as the only recourse? Tragically, for both Nur and Sherwani, the phenomenon of death becomes not only the phenomenon of enlightenment of the difference between the moral and immoral structures of human values, but also the justification of a spiritual interjection of pity.

Ironically, Anand’s picture of the British colonial-imperial India of the thirties in

Lament

presents a diseased social order where the function of education, apparently after the Macaulayan system of education, has been constricted to producing

babus

,

where family structures are based not on love, compassion and understanding but on the false notions of prestige (

izzat

) and selfishness, and where community seems to lack the basic sense of human values. It is not surprising that Nur, in order to become a

babu

,

‘a deputy collector sahib,’ must get the degree of Master of Arts. But the M.A. degree does not help him to obtain any high-ranking position, for he belongs to a lower class in the social hierarchy. As a confectioner’s son, he cannot compete with other students from upper-class wealthy families. It is rather unfortunate that he cannot take any menial job to feed his family. Now that he is suffering from tuberculosis and is confined to bed, he wants to die. Hence, the famous first line from his own poem, ‘Why did you drag me into the dust by making me an M.A.,’ a line that constitutes the thematic centre of Nur’s tragedy. His painful poetic realization that his education finally led to his tragic failure in life is only a partial realization of the whole process of dehumanization that apparently has been unavoidable to prevent. But who is responsible for this ineluctability? It is Gama’s role as a dramatic functionary that helps Nur in the psychological process of reminiscing almost unreservedly. In fact, this psychological process of delving into his own consciousness and hence of unburdening himself of the unforgivable weight proves to be cathartic. His education had prepared him only for the position of a subordinate pillar of the colonial regime of the periphery, but it did not nurture his creative imagination, his poetic vision. Hence, the interjectionist reference to Azad’s education, his vision of India and his influence on Nur: ‘He initiated me into the mysteries of poetry . . . . The passion, for instance, he put into the reading of books . . . the slow gradation of Heine’s love poems . . . the lyrics of Goethe and Iqbal . . . the broad histrionic gesture of Mercutio in

Romeo and Juliet

. . . the comic overtones of Dickens and the polished undertones of Flaubert . . .’ Nur assures Gama ‘that we felt we knew what was wrong with India and with ourselves . . . .’ One wonders if the problem with India as identified by Nur and Azad is its subjugation and hence the lack of proper education of its citizens.

Nur is quick to identify the vulgarity and unfairness of the social structure: ‘The whole world is in search of happiness . . . it is vulgar and stupid, the way in which society distributes her favours. The bitch has no morals. She yields herself to the embraces of any robber . . . .’ Surely, this is Anand’s fierce and bold indictment of the structure of social values, one that denies equality, liberty and justice to its people. It is even more painful to see Nur’s continued suffering at home. His father, the Chaudhri, is the most arrogant, heartless and abusive person whose wrongful and cruel expectations of his son have finally driven him to a fateful death. The Chaudhri’s frequent rage forces him to imprecate his son: ‘Go to hell and be done with it, die and rid us all of this responsibility.’ One wonders if Chaudhri’s vituperative language is a complicated integument of something more tangible in the relationship between father and son. Nur’s mother had died sometime back and his father had remarried. The only sources of some comfort to Nur are his wife, his daughter and grandmother. Ironically, Iqbal came into the Chaudhri household as Nur’s wife in a negotiated marriage, but she has been sent back to her parents. Apparently, there is no solution to Nur’s suffering. Ultimately, death intercedes and delivers Nur from the wretchedness of his existence. But Nur had been able to penetrate into his inner consciousness in order to see the reality of his existence. The function of Gama and the lucid reference to Azad proves to be an indispensable revelatory technique for Nur to experience what had so far remained essentially hidden in his consciousness. Now that he has seen the truth with this release, he can die peacefully.

While Nur’s death in

Lament

provides him cathartic relief, Maqbool Sherwani’s death, tragic as it is, becomes a testing point of the protagonist’s poetic idealism. It is true that Sherwani returns to Baramula to persuade his friends to endorse the cause of liberty of the Kashmiri people and to oppose the Pakistani intruders. Here, one wonders if Sherwani, the poet-teacher, really understands the truth of his mission. Paradoxically, Sherwani finds himself trapped in a direct confrontation between the world of reality and the world of idealism. His embarrassing discovery that most of his friends in Baramula have already crossed over to the Pakistani invaders and are in fact trying to force him to follow them leaves him nonplussed. It is here that one finds Anand’s mastery in portraying the realism and the truth of the human condition. Although Sherwani finally gets caught and is punished and murdered by his captors, he does not submit to their demands. Nor does he compromise with his idealism. It is indeed very true that his imprisonment by his captors does not weaken his idealism. On the contrary, his commitment to the cause of liberty becomes stronger. Riemenschneider rightly admires Anand’s effort and strategy: ‘

Death of a Hero

, indeed, is not only the deepest probe into the potentiality of man but also most satisfying artistic achievement.’ Sherwani’s death becomes a messianic sacrifice and hence the emblematic triumph of the human values that constitute the very core of Anand’s humanism. Sherwani’s letter to his sister that he wrote during his imprisonment simultaneously marks the triumph and also the continuity of the impact of art on civilization.

In the Postscript to

Apology

,

Anand has raised the question of the inveterate need to know the truth of the human condition and the human values that strengthen the human condition. In this search, then, can the human imagination eradicate the problems of human suffering, pain and subjugation and can humanity at large seriously consider

karuna

(pity) an interjectionist alternative and a fundamental and integral human value? ‘The Buddhist

Karuna

, or compassion,’ explains Anand, ‘which is neither contempt from above, nor sentimental love from below, but a tender recognition of the essential similarity, both in strength and frailty, of human beings, becomes for me the pervasive starting point of comprehension for each feeling, wish, thought and art that constitutes the world behind the scene of the human drama, from which catharsis of ultimate pity may arise.’ Interestingly, in his letter to his sister, Sherwani maintains that pity is dependent on one’s conscience and that when fully realized, ‘pity is poetry and poetry is pity.’

K. D. Verma

University of Pittsburgh–Johnstown, U.S.A

2011