Type-II: Memories Of My First House

Read Type-II: Memories Of My First House Online

Authors: Abhilash Gaur

Tags: #childhood, #memoir, #1980s, #1990s, #chandigarh, #csio campus

Of My First House

By Abhilash

Gaur

Copyright 2014 Abhilash Gaur

Smashwords Edition

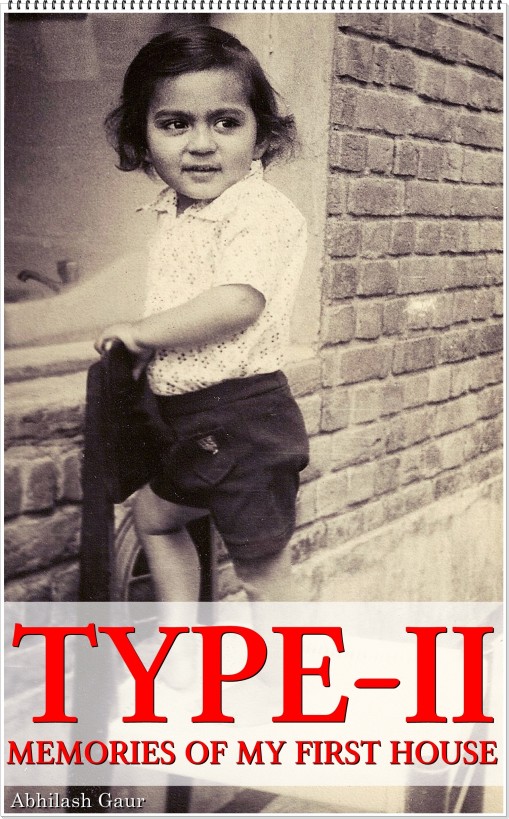

Cover Photo: S C Sharma

***~~~***

Thank you for

downloading this ebook. You are welcome to share it with friends.

This book may be reproduced, copied and distributed for

non-commercial purposes, provided it remains in its complete

original form. If you enjoyed this book, please return to your

favourite ebook retailer to discover other works by this author.

Thank you for your support.

***

From the second

day of my life to the time I was 19 years old, I lived in a small,

one-bedroom flat on the top floor of a three-storey building in

Chandigarh’s CSIO Campus. It’s the longest that I have lived in one

house. Since leaving it in 1996, I haven’t stayed at any one

address longer than five years, and I doubt any house now will

serve me for two decades.

That house had

many problems. It was infernally hot in summer and bitingly cold in

winter. Rainwater seeped into its walls and stained them, but the

taps mostly remained dry. And it wasn’t big enough for a family of

four. Yet, I haven’t loved any other house like it. It was the only

one for which I felt a sense of belonging.

But this book

isn’t all about that house. It isn’t, strictly, a memoir of my

childhood either, although it is both in parts. It’s about a way of

life that I miss very much. If my childhood is a scene hanging on

the wall, this book is all the things that my eyes alight on first.

I was equally fond of my school, St Anne’s in Sector 32, but I have

written about it in detail in my book,

Super Days

. Here, I have tried to remain within the

compass of CSIO Campus, and to prevent the narrative from extending

beyond my teens, I have anchored it to that small house on the top

floor.

Why call this book

‘Type-II’, you may ask. Because that’s how the government

classified my house. It was a Type-II house, and my parents’

abiding prayer was to someday graduate to a bigger, warmer

Type-III. They eventually made it to Type-IV with all the comforts

they missed. But I still miss my Type-II.

***

To my parents,

who undoubtedly remember more of it, and Ritika, who is not a CSIO

girl

***

I remember, I

remember,

The house where I was born,

The little window where the sun

Came peeping in at morn...

-Thomas

Hood

***

We were a

family of four: papa, mummy, my sister and I. I was the youngest,

six years my sister’s junior. In my earliest pictures she’s at my

side, supporting me gently, a slim little girl with shoulder-length

hair, wearing a flower-print sleeveless frock. I can’t tell you the

colour because the photos are all black-and-white. But later, I had

a shirt of the same cloth. Mummy altered it for me, no doubt. I

envied my sister for being older. I have heard she dropped me once,

but I wasn’t harmed.

We lived in a

three-storey red-brick building inside a sprawling campus that

could have been greener than it was. Large plots of ground inside

it wore an untended look, overgrown and bald in patches. The campus

was bounded by brick walls of the same, unplastered red.

CSIO Campus,

Sector 30-C. It was an impressive name, more so when expanded:

Central Scientific Instruments Organisation. Papa’s office was

inside the campus, and it was a boon to us because he used to get

home within five minutes of closing time. Mummy would brew tea in a

steel tumbler at 5.30pm sharp, and as soon as she heard his step at

the door, she would boil a little milk, so that by the time he

washed and settled down at the table, tea was ready.

I remember little

of the office, and the first thing that comes to mind is a white

sign with cold blue flaking letters: ‘Photography Is Prohibited’.

It taught me the word ‘prohibited’.

Other than that,

let me see, there was a library from where I got my first science

fiction books. During summer vacations, papa brought old Time Life

books on a variety of subjects. I started my first diet in class 6

after reading one of them, but when I look at old photographs of

that age, I realise I shouldn’t have. Once, there was talk of papa

being sent to Syria, and one of the books he brought was about that

country. Only, it was published in the 1960s while we were living

in the late-1980s. Not the best reference book for our purpose.

Twice every year,

the office was open to children for Science Day and Foundation Day.

And on one of those days, near the end of the rainy season, there

used to be an essay writing competition in a low, red-brick

building inside the ISTC area. I think every child won a prize in

it. Prizes were distributed inside the office auditorium where the

ceiling dripped in a downpour. One year, I skidded in my slippers

while hurrying to the stage. I didn’t fall but people noticed, and

my ears still burn with embarrassment when I think of it.

Sometimes, in the

early years, old movies were screened in the auditorium. I remember

Jab Jab Phool Khile because it left me smitten with Nanda and her

impossibly coiffed hair. Later, I saw You Only Live Twice with a

friend. It remains the only 007 movie I have seen on the big

screen.

The year Halley’s

Comet came, 1986, telescopes were set outside the office building

at night for sighting. There was a mad rush, and although I got a

turn at the eyepiece, I am not sure I saw what I was supposed to

see.

There, that’s all

I can think of.

***

When I think of

the campus I grew up in, all that empty space, I feel happy, but

also sad because space is at a premium now and I will never again

have so much of it.

At home, I learnt

to call it CSIO Colony. Later, I started calling it ‘campus’ like

the more sophisticated older children I moved among. There’s

snobbery in these fine distinctions. Colonies are down-market:

labour colony, jhuggi-jhonpri colony, Rajiv Colony, Kumhar Colony,

Kathputli Colony. If it’s a slum it’s bound to be a colony.

Pre-Independence, the whole of India was a colony. But campus,

there’s nothing dirty or smelly about the word.

The red,

naked-brick buildings of CSIO Campus weren’t really red at the time

from which I have my first memories. Every rainy season a green

velvety moss covered the cracks and the pores of the bricks, and

when it dried, it turned sooty black. Year after year, the walls

became more and more mottled, and in truth I only remember them as

dirty and black-patched.

We lived on the

top floor of a three-storey building. It helped me learn the

distinction between American and British floor conventions. We were

on the second floor but the third storey. Our house was of the

smallest type—Type II—with two rooms, one of which was our

drawing-cum-dining by day and became a bedroom for papa and me at

night.

I spent 19 years

in that house, the longest I have lived in one place, and it was

the only one I became attached to although it had a hundred

shortcomings. My parents were always looking forward to moving out

of it. Once or twice every year, their hopes rose. This or that

house had been vacated. But always, somebody else got it. And I was

happy to stay put. It was my house after all, the one to which my

parents brought me straight from Government Hospital Sector 16.

Four narrow and

steep flights of stairs led up to our floor. During the day,

sunlight from a brickwork screen that fronted the building lit them

up. And after dark, dim bulbs at the top of each side wall painted

them yellow. The stairs were too narrow for two people to pass

comfortably, and the whitewashed walls got chipped every time a

family moved in or out with its furniture.

Often, the 60-Watt

incandescent bulbs at the top of the stairs ‘fused’ and imaginary

ghosts and demons invaded the dark space between the ground and my

house. Then I crept up slowly, clinging to the cold and thick iron

railing that smelt like flint wheels that produced sparks inside

toys those days. Perhaps, sulphur from sweaty hands gave it that

smell.

I was afraid of

the gaps in the banister but not as much as of the lizards that

crawled on the walls. Sometimes, a stray dog made its home on a

landing of the staircase and then I had to retreat timidly, stand

under our bedroom window and shout for papa or mummy to come and

fetch me upstairs.

Those stairs had a

special place in our daily life. Of course, we needed them to get

in and out of home, but we children also played on them when the

weather was too hot to go outside, or it was raining. My favourite

game was to jump off steps. Three steps was a good start, and by

the time I was in senior school I could do seven or eight. We made

a loud ‘dhum’ sound on landing, and if two or three of us were

playing, one of the ground-floor aunties whose siesta we had broken

was bound to step out and reprimand us gently.

The stairs were

also a place to swap notes between ground and upper floors. It was

a sign of warmth to continue conversing with departing guests in

the staircase. If you saw somebody off at your doorstep, you were

being cold and rude. But if you went down all the way to the ground

floor, and even to the turn of the road, your affection for the

visitor was deemed genuine. At times, we saw people off right up to

their doors. Even if you didn’t go that far and lingered long

enough in the stairs, talking and laughing over the banister, you

showed your heart to be in the right place.

There was a boy on

the ground floor, one year my senior at school. His father had

studied more than papa, and was at a higher position too. But I was

too small to understand this. One evening, after his father and

mine had returned from work, we argued loudly about whose father

was smarter. When I came home after giving him a mouthful, I found

my parents sitting in armchairs at our centre table and suppressing

their laughter. They had heard every silly word through the front

door that was always open.

On Diwali, we lit

candles and diyas on the railing and in the squares of the brick

screen as high as our hands could reach. Not many people used

decorative electric lights those days, and even those who used

seldom had anything longer than a metre or two, with about a dozen

round bulbs encased in red plastic cherries. If it was a windy

night, and most Diwali nights started out windy, the diyas died out

repeatedly and the candles fought against the draught valiantly,

the flames feinting this way and that like a skilled swordsman. The

light was dimmer but the sight more beautiful than anything rolls

of blinking Chinese lights can conjure today.

***

Not one house

in our block had a telephone at the time, and news of family and

friends arrived by real mail: letters and postcards. The postman

came every afternoon without fail, unless it was a Sunday or a

public holiday. By the time he reached our block it was noon,

sometimes he came just minutes before papa walked up the stairs at

lunchtime.

The postman rode

up to the first ramp of the stairs at ground level and rang his

cycle bell. And unless it was something special, a telegram or a

money order, he left the letters on the highest stair his hand

could reach from the bicycle saddle. Everybody knew his bell. Doors

unlatched together and slippered feet pattered downstairs to grab

the day’s mail. Nobody got letters every day, but some people

seemed to get a lot of junk mail. There were roughly printed

pamphlets in Hindi and Urdu, seemingly about medicine and politics

and poetry, completely impersonal but for the handwritten name and

address. Our neighbours must have had diverse interests, I

guess.