Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (62 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

The Penn Station stands at Sections 130 and 515 have a decent

Philly Cheesesteak

and even better

Hand-Cut Fries.

The Reds kindly offer two

Kids Zone Stands,

behind Sections 132 and 533, where you can buy hot dogs, popcorn, peanuts, sodas and ice cream cups for $1.00 each. Hand these small-sized items to your youngsters or eat them yourself. No one checks to make sure you’re actually toting kiddies. The lines sometimes get long as the game wears on, so do take advantage of this good deal before first pitch.

The

Cheese Fries

are a nice option for those who like their deep-fried foods. Fried on the spot but not overly greasy, they’re warm all the way to the bottom. And the cheese sauce has a nice spice to it.

Great American Ball Park features much the same beers available everywhere else in the Western world except for Redlegg Ale. This microbrew specialty is brewed by Barrel House Brewing Company, located at 22 E. 12th St. in Cincinnati. The neighborhood is a bit dicey if you’re planning to visit. But this brew is not too shabby, and we like the name.

Speaking of suds, the Redlegs were expelled from the National League in 1880, in part for selling beer at the ballpark. This outrage kept the Reds out of the NL for ten seasons. They were reinstated in 1890, and thus far they have stuck.

Reds fans are a serious breed, a veritable army of devotees donning red. Their team accomplished big things in the 1970s and is looking to repeat that magical decade with another dynasty. The field itself is known to favor hitters, as Great American usually ranks among the top five easiest big league parks in which to homer each season. This is particularly so when left-handed pull-hitters—like former Reds slugger Adam Dunn—are at the plate, seeing as the right-field fence is closer to the plate than the one in left and the breeze tends to carry balls toward the river. This tendency has earned the stadium the nickname “The Great American Small Park.”

Most every Reds fan is as rabid as heck and willing to talk your ear off about the time Tony Perez signed their baseball on his way out of the Riverfront parking lot, or

the time they were at Great American to witness a walk-off homer by Brandon Phillips or some other recent Red. However, some Reds fans are just a little more rabid than the rest.

Cyber Super-Fans

- Red Reporter

If the Reds ever go out of business, these Web masters can use their address for a communist newsletter. But for the time being, everything about the site is democratic and informative.

- Cincinnati.com

http://cincinnati.com/blogs/reds/

A good blog featuring the insights of the local beat writers.

- Red Leg Nation

We like the “Pulse of the Nation” polls and funny Reds

T-shirts.

Mr. Red, for example, is a seam-head if ever we saw one. He’s a mascot whose actual head is an oversized baseball. We’re not sure if he’s related to Mr. Met but we think it’s a pretty good bet. Maybe we’ll ask Tom Seaver—who pitched for both teams—the next time we see him. In any case, Mr. Red cheers for the Reds during games, and attends functions all over Cincinnati while they’re on the road. He has represented the Reds very well over the years and is sometimes joined by his crush Rosie Red and his handlebar-mustachioed uncle Mr. RedLegs.

For kids who are a little freaked out by ball-heads—let’s be honest, aren’t we all a tad spooked by them?—Gapper is a whole different breed of fanatic. With a furry red face and pointy blue nose, Gapper looks like a prankster and plays the part to perfection. So beware.

If you’re unattached and hoping to make a new friend or two during your trip, you’ll be happy to learn that every Friday night game at Great American is designated a “Free Agent Friday.”

Josh:

Free Agent Friday? I don’t like the sound of that.

Kevin:

Sounds like trouble.

All this really means is that before Friday night games the Reds encourage single men and women to congregate at the Fan Zone in left-field home run territory for mixers that feature drink specials, a DJ spinning tunes, and the lovely Mynt Martini girls making the rounds. The fun begins at 5:40 p.m., allowing smooth operators just enough time to get to first base by game time.

On special Free Agent Fridays the Reds play up the dating theme all night. They’ve held “Battle of the Sexes” trivia nights, “Speed Dating” nights, dancing contests, and even a “Win a Girl” contest that was sort of like the TV show

The Bachelorette,

only instead of getting married at the end, the two winners watched a game together in an improved seating location. We should also mention that the Reds have fireworks at the ballpark after every Friday game all summer long. And what’s more romantic than fireworks?

Sports in the City

The Three Incarnations of Crosley Field

The first tribute to Crosley Field in these parts is Crosley Terrace, located outside the ballpark. That one’s easy to check off your list.

The second site is the corner of Findlay and Western Streets where a plaque marks the former location of Crosley. A janitorial supply company operates on the corner now, but six seats from Crosley sit outside the front door.

The third and most comprehensive site is located in Blue Ash, Ohio, where the Crosley Sports Complex features replica baseball fields of Riverfront and Crosley. Just like at the original Crosley, a banked outfield rises to the home run fence and a Longines sits atop a replica of the scoreboard. The lineups posted on the board are from the final game at Crosley, June 24, 1970, against the Giants. Ticket booths and a section of seats from the old park are on display in Blue Ash as well. And along the dugouts, plaques honor visitors to the field like Dave Concepcion, Dave Parker, Johnny Bench, Cesar Geronimo, George Foster, Blue Moon Odom, Danny Ozark, Ken Griffey Sr., Walt Terrell, Pete Rose, and others. Many are autographed. Some players have written their uniform numbers as well as their names on their plaques, and some have drawn smiley faces. Josh tried unsuccessfully to trace several autographs onto a ball. To get to the Crosley Sports Complex take Route 71 to the Blue Ash exit. Follow Glendale Milford Road toward Blue Ash. Turn right onto Kenwood Road, another right on Cornell Road, then take a left onto Grooms Road. The complex address is 11540 Grooms Rd.

Sports in (and around) the City

The Louisville Slugger Museum and Bat Factory

800 West Main St.

Whether on your way to St. Louis or Kansas City, a trip to Louisville offers the chance to marvel at the biggest baseball bat in the world. The 120-foot-tall, 68,000-pound whopper is made of steel, but painted to resemble the wood grain of a real bat. It rises higher than the five-story brick building it leans against, serving as a beacon for those in search of the Louisville Slugger Museum.

Inside, exhibits trace the evolution of the bat, offering examples of the sticks that famous sluggers like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Ted Williams wielded, as well as models that modern players like Derek Jeter, Ken Griffey Jr., and David Ortiz swing. Another popular attraction is a twelve-foot-long baseball glove made of 450-year-old Kentucky limestone, in which children can sit and play. The glove weighs seventeen tons and could only be installed after the Museum’s front doors were removed to allow for its entrance.

The twenty-minute tour of the Hillerich and Bradsby factory demonstrates how planks of white ash and maple harvested from the company’s 6,500 acres of forest in Pennsylvania and New York are lathed into the best baseball bats in the business. Hillerich and Bradsby sells more than one million bats a year, thanks largely to the more than 60 percent of current major leaguers who swing its popular Louisville Slugger. The typical big leaguer goes through about one hundred per season.

The woodworking shop that grew to one day become the most prolific bat-maker in the industry was founded in Louisville in 1856 by German immigrant Fred Hillerich. In those early days, the shop made balusters, bedposts, bowling pins, and butter churns, not baseball bats. Then in 1880, according to local legend, Bud Hillerich began work as an apprentice in his father’s shop. When Fred wasn’t looking, his son made baseball bats for himself and for his friends. Then one day young Bud made a special bat to help his favorite player out of a horrific slump. Pete “The Old Gladiator” Browning was the star of the American Association’s Louisville Eclipse, but he was really struggling in the early part of the 1884 season. He couldn’t buy a hit and was willing to try anything to change his mojo. So on a warm spring day he stepped into the batter’s box with one of Bud’s handmade bats on his shoulder. Before long Browning was knocking balls all over the yard. He went on to bat .336 that season and never swung another type of bat until his retirement from the game ten years later. By then word had spread. Many other major leaguers were swinging Louisville Sluggers too, including Pittsburgh Pirates star Honus Wagner, who helped cement Hillerich and Bradsby’s place in the game when he signed an endorsement deal with the company in 1905. Then Ty Cobb signed a similar contract in 1908.

Today, the Museum that tells the story of this unique American enterprise is open Monday through Saturday from 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m. and Sunday from noon until 5:00 p.m. Factory tours run every day but Sunday, and every fan who takes the tour receives a miniature souvenir bat.

Now, you may be wondering how the Reds would get any available ladies to turn out for one of these pregame mixers. After all, we statistic-citing, sausage-slobbering baseball fanatics have not exactly excelled on the dating scene historically. So how do the Reds do it? Very simply: with chocolate and Cyndi Lauper. When we visited during 2011, a Free Agent Friday had drawn a fair number of females to the Fan Zone before the game where they were enjoying not only a chocolate-dipping fountain but free massages from a local parlor, and other beauty enhancement booths. Then, the fireworks exploded after the game to the crooning of Ms. Lauper and other female singers.

Josh:

I have a feeling Reds fans are gonna hate us for including this section.

Kevin:

Yeah, but the Pink Hats will love us.

Josh:

Do they have Pink Hats in Cincinnati?

Kevin:

More like light-red hats, I suppose.

One of the game’s most recognizable super-fans of all time got her start in Cincinnati in 1971. Morganna was an exotic dancer whose “baseball stats,” as she called them, measured a mythic sixty by twenty-three by thirty-nine inches. She used her considerable bust and bubbly personality to make her presence known throughout the game in the 1970s and 1980s as her “victims” came to include Frank Howard, Johnny Bench, Nolan Ryan, Cal Ripken Jr., George Brett,

Don Mattingly, Steve Garvey, and many other stars. But Morganna’s very first ballpark smooch occurred at Riverfront Stadium, when at the age of seventeen, she bounded out to Pete Rose and planted a big wet one on him. Rose reacted angrily and chewed her out, but then the next day he turned up at the lounge club where she was performing and apologized with a dozen roses.

We Played “Schott for Brains”

We put our heads together to assemble a list of the five most deplorable things Marge Schott said and did while running the Reds from 1984 until 1999. So, with apologies to the late George Steinbrenner, whom we may have erroneously called the most arrogant moron to ever own a big league team, here goes:

- Schott instituted a St. Bernard named Schottzie as the Reds mascot, named after herself rather than anything to do with the team. Schottzie, who smeared the Astroturf at Riverfront with his leavings, eventually became the first mascot banned from his home park. You know what they say about pets taking on the personalities of their owners? Well, the players, fans, and pretty much everyone else associated with the Reds other than Marge eventually came to hate the obnoxious mutt. And Schottzie II was even worse.

- Schott once said she didn’t like her players wearing earrings, because “only fruits wear earrings.” She later apologized for her remarks, saying that she was “not prejudiced against any group, regardless of their lifestyle preference.” Later, pitcher Roger McDowell bought earrings for the entire team to wear.

- When umpire John McSherry collapsed on the field and died, Schott’s comment was: “Snow this morning and now this? I don’t believe it. I feel cheated. This isn’t supposed to happen to us, not in Cincinnati. This is our history, our tradition, our team. No one feels worse than I do.” Once again, Schott later apologized for the insensitivity of her comments.

- When questioned in an interview about owning a swastika armband, Schott responded, “Hitler was good for Germany in the beginning, but he went too far.” She was again fined by the league and suspended for a full year.

- Schott used highly offensive racial slurs in referring to two of her own players—Eric Davis and Dave Parker. She later apologized but was fined $25,000 by MLB and suspended from the Reds’ day-to-day operations for nine months.

PITTSBURGH PIRATES,

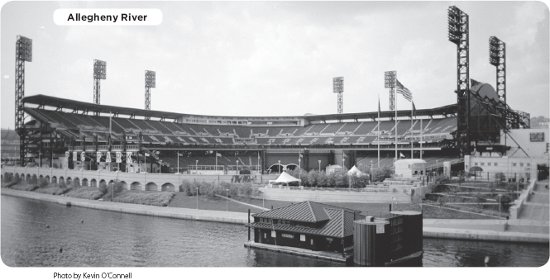

PITTSBURGH PIRATES,PNC PARK AT NORTH SHORE

Raise the Jolly Roger along the Allegheny

P

ITTSBURGH

, P

ENNSYLVANIA

132 MILES TO CLEVELAND

245 MILES TO WASHINGTON

250 MILES TO BALTIMORE

285 MILES TO DETROIT OR CINCINNATI

T

he plan to build PNC Park, bring about a return to Pirate dominance, and appease the Pittsburgh fan base seemed simple enough. It was certainly efficient. And it seemed well thought out. The details went something like this: Step One: Build the finest new ballpark in America, one centered in a region where its citizenry is all but addicted to sports. Step Two: Reap massive increase in ticket sales and use accompanying profits to build a championship-caliber team. Step Three: Wallpaper the bathroom with pennants and build a new case for all the trophies sure to follow. And oh yeah, and don’t forget about making some space in the basement for all of the victory champagne that would surely be needed.

Ah, but what is that famous saying about “the best laid plans of pirates and men?” Who besides John Steinbeck himself could have known things would go so horribly wrong for the Pirates? Team management knocked off Step One with relative ease. They built a very fine ballpark. PNC is beautifully crafted with local steel and brick. It has nary a bad seat. With a backdrop of the city’s panoramic downtown, the view across the Allegheny River is surpassed by no ballpark in America. And PNC remains within spitting distance of where part of the first-ever World Series was played, on Pittsburgh’s North Shore. All should have been right with the Bucs’ world.

However, steps Two and Three have proved trickier to realize. Let’s see if we can figure out where things went awry.

Prior to the opening of PNC Park in 2001, the Pirates played their home games at the much loved Three Rivers Stadium. Located between where PNC now resides and the Steelers’ Heinz Field on a site that now houses a parking lot and outdoor amphitheater, Three Rivers was the site of the greatest era in the history of Pittsburgh sports: the 1970s. That memorable decade earned Pittsburgh its familiar “City of Champions” moniker. The Pirates nabbed two of their five World Series crowns at Three Rivers, in 1971 and 1979, while the Steelers tallied four Super Bowl rings between 1975 and 1980. It was, as they say, a glorious time to be a fan in “Da Burgh,” and gave the city a much-needed shot in the arm and ego, as the decline of the region’s famed steel industry had Pittsburghers feeling mighty low about themselves and their future prospects.

Few Pittsburghers complained that Three Rivers was a multisport stadium that could have easily been swapped out for “The Vet” in rival Philadelphia (God forbid) or for Busch Stadium in St. Louis without too many people noticing. There weren’t many letters to the editor being written by fans demanding the delights of baseball played on natural grass or before open views of the city rather than a wall of orange and yellow seats so high it blocked the sun and rested on concrete decks so steep that a Sherpa would have been more useful than an usher. Few even seemed to mind when the concrete began to brown with age. No. Pittsburghers liked Three Rivers Stadium quite a lot, thank you very much.

Josh:

Is it true you can buy pictures of the implosion suitable for framing?

Kevin:

You can still buy snow globes with Three Rivers inside.

Josh:

They probably don’t sell many snow globes of the Kingdome in Seattle, do they?

Kevin:

No. Because it rarely snows there.

Why such undying devotion to an ugly relic from a suspect era of stadium design? The sweet memory of victory, of course. Winning heals all wounds. And Pittsburghers enjoyed some pretty incredible moments during the life of that big ugly ship at the confluence of the town’s three trademark rivers.

The last game Roberto Clemente ever played was at Three Rivers. Willie Stargell led crowds in singing “We Are Family” all the way to the 1979 championship. Franco Harris made the Immaculate Reception on the Three Rivers turf in the 1972 NFL playoffs. “Mean” Joe Greene gave a kid his jersey in the Three Rivers tunnel in a famous Coke commercial. Mega-rockers and J.R.R. Tolkien enthusiasts Led Zeppelin played there, as memorialized in the documentary film

The Song Remains the Same.

And who could forget Pete Rose, one of the celebrity endorsers of “Hands Across America,” locking hands at Three Rivers with his Reds teammates and Little Leaguers alike in 1986? Ah, sweet memories. Despite its relatively short life—it opened on July 16, 1970, and was imploded on February 11, 2001—the field sure hosted some amazing moments.

More than fifty-five thousand fans turned out on October 1, 2000, to watch the Pirates play their final game at Three Rivers, a loss to the Cubs. It was the largest crowd ever to see a regular season baseball game in Pittsburgh. Three Rivers had served the Pirates since July 16, 1970, when they also lost to the Cubs. Baseball, like history and Josh when he’s telling fishing stories on long road trips, tends to repeat itself.

Josh:

Did I ever tell you about the time I caught an eel in a quarry pit?

Kevin:

Yes, you told me when we were in Cleveland last week.

Considering all this warmth for Three Rivers that Pittsburghers held in their hearts, the question arises: Where did the need arise to build a new ballpark? In essence, the sun was setting on the era of the multi-purpose monster stadium, and the era for each sport to build its own ballpark was dawning. The Pirates were simply smart enough to figure this out and capitalize on the phenomenon—though not completely without trouble. With the Pirates struggling in the mid-1990s and some of the team’s corporate owners wanting out, management threatened to sell the team to another city if a local buyer couldn’t be found. Finally in 1996, a group led by Kevin McClatchy purchased the Pirates with MLB’s condition that the city would build a new baseball-only facility within five years. As is the case in most cities, though, wanting a new park was the easy part. Figuring out who should pay for it turned out to be more difficult. A sales tax increase was brought before voters to finance a new baseball park, a new football stadium, and a new convention center that city officials had long discussed. Taxpayers twice rejected this hike in all eleven counties in which it was proposed.

Pittsburgh Mayor Thomas Murphy viewed the Pirates as a brand name of the city and drove the metaphorical stake in the ground to keep the stadium project moving forward. Even though taxpayers voted a resounding “no,” Plan B was put into effect. We’re not kidding, the plan was actually called “Plan B.” According to the plan, the Regional Asset District Board, which administers the funds raised by 1 percent

of the sales taxes already in place, guaranteed the ballpark project $13.4 million dollars per year for thirty years, giving the new ballpark the anchor it needed to continue. The Pirates chipped in $44 million more, $30 million of which came from PNC Bank for the naming rights. And while we would have liked to see the funding come totally from private sources, at least taxes weren’t raised to finance the ballpark when people had clearly voted against that measure. Then Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge granted the remaining $75 million in a deal that brought new football stadiums and ballparks to both Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. As we’ve seen elsewhere, none of the politicians felt their careers could suffer the blame for the home team leaving because of finances.

Josh:

Now that we have the Tea Party do you think pols will spend as liberally on new stadiums?

Kevin:

I think we’d better leave the politics to George Will and Arianna Huffington.

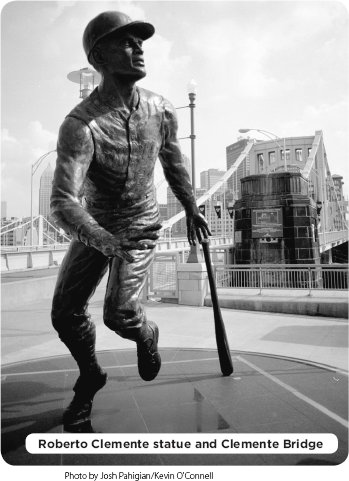

The total cost of PNC was to be $262 million, with the construction timeline scheduled to span an ambitious twenty-four month schedule. On April 7, 1999, a groundbreaking ceremony was held for PNC Park, and the Sixth Avenue Bridge was officially renamed “The Roberto Clemente Bridge.” A very classy move by Pittsburgh, which had not always treated Clemente with the respect he deserved.

Ever since the Pirates had left Forbes Field, some Pittsburgh baseball purists had remained haunted by the ghost of a beautiful ballpark they’d once enjoyed: their own steel green cathedral. The brown dirt, the green grass, the blue seats, the brick walls, and the cozy confines Forbes had provided for so many years howled and moaned in the memories of old-timers seated in cavernous Three Rivers. And the Pirates wanted the glory and the memory of Forbes back. They wanted the luxury boxes, club seating, and wide concourses and concession areas of modern parks too, and they wanted it on the North Shore.

Kevin McClatchy has been much maligned for his captainship of Pirate Nation. And while it is true that during the years McClatchy was majority owner (1996–2007) the Pirates never posted a winning season, his legacy will always be PNC Park. McClatchy oversaw every detail of the design and building of PNC. And let us say for the record that in this regard McClatchy’s work was exemplary. PNC is the most intimate, and perhaps most beautiful, ballyard of the recent ballpark renaissance. On April 9, 2001, the Bucs opened PNC Park at North Shore, which not only brought back natural grass to the Burgh, but synthesized many elements of the old-time ballparks with the best elements of the new. PNC is the Pirates’ fifth home and is very much an alloy of Pittsburgh’s storied baseball past, combining features of the other parks the Pirates have called home.

PNC was built with unique local materials. Steel has been used in every ballpark and stadium since the construction of Forbes Field, but more than just providing structural support, it is a featured part of the beauty and strength of PNC. There is more exposed structural steel and decorative brushed steel at PNC than at any other park, and nowhere is it more fitting than in Pittsburgh, the city that made U.S. Steel King. A yellow limestone called Kasota stone replaced the red brick that has nearly become a retro cliché among ballparks built over the last two decades. In 2010, this same Kasota lime would debut on the façade of the Twins’ new

Target Field in Minneapolis. This distinctive stone is also used prominently in other buildings in Pittsburgh. Throughout the city and at the park, it suggests a certain warmth and friendliness that seems to invite would-be visitors inside. PNC was designed with the visitor in mind—specifically fans who like to watch baseball games. This might sound more obvious than it actually is, but there are few extras at PNC to detract from fan focus.

Kevin:

With the way the Pirates have played the last two decades, a little off-the-field distraction might not be such a bad idea.

Josh:

There’s a pirogue race going on, quiet down.

PNC is not an amusement park or entertainment venue. Its sole purpose is to get fans close to the ballgame so they can enjoy it. This single minded devotion has made PNC a no-frills shrine to the game itself. You will find no carousel here, no roller-coaster, no circus clowns. Heck, it took us twenty minutes to find the kiddie area—which, by the way, was tastefully done in a tiny baseball park within the ballpark theme. What does all this add up to? A ballpark, built in the old style, the way it should be, with distinctive local materials and all the modern amenities required for the new era, PNC is a thoughtful return to all that was good about the small and glorious ballparks of yesteryear. It accomplishes this without sacrificing the wide concourses, comfortable seating, and cup-holders that enhance the experience of new ballparks. So as it was in the beginning, so shall it ever be, a world without end. Amen.