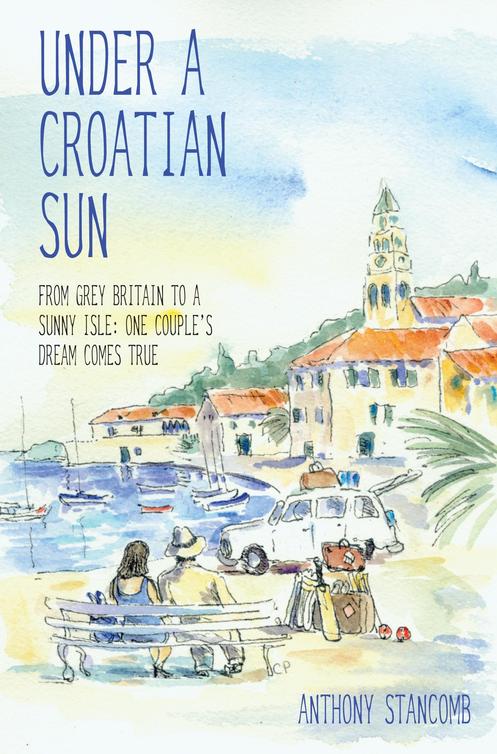

Under a Croatian Sun

Read Under a Croatian Sun Online

Authors: Anthony Stancomb

- TITLE PAGE

- CHAPTER 1 APRIL ARRIVAL

- CHAPTER 2 FIRST STEPS

- CHAPTER 3 KARMELA

- CHAPTER 4 THE ROAD TO THE ISLAND

- CHAPTER 5 TRYING TO FIT IN

- CHAPTER 6 COFFEE HOUSING

- CHAPTER 7 LOCAL CUSTOMS AND LOCAL TRANSPORT

- CHAPTER 8 MEDICINE MATTERS

- CHAPTER 9 CHILDREN AND GRANNIES

- CHAPTER 10 HOME AND GARDEN

- CHAPTER 11 AN ENGLISH LEGACY

- CHAPTER 12 NEIGHBOURS

- CHAPTER 13 COOKING

- CHAPTER 14 THE LEGACIES OF WAR

- CHAPTER 15 MESSING ABOUT IN BOATS

- CHAPTER 16 ADVENTURE AND ATTITUDE

- CHAPTER 17 MUSICAL EVENINGS

- CHAPTER 18 ISLAND ROMANCE

- CHAPTER 19 LOST IN TRANSLATION

- CHAPTER 20 A PROJECT AT LAST?

- CHAPTER 21 MISPLACED ECOLOGY

- CHAPTER 22 ANOTHER PROJECT AND YET MORE FRUSTRATION

- CHAPTER 23 MORE BRITISH LEGACY

- CHAPTER 24 THE DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD OF PROGRESS

- CHAPTER 25 WINE AND THE ART OF CRICKET PRACTICE

- CHAPTER 26 IMPROVING RELATIONS

- CHAPTER 27 THE PITCH AND THE MATCH

- CHAPTER 28 RETURN TO THE METROPOLIS

- CHAPTER 29 THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES

- CHAPTER 30 THE STAR CROSS’D LOVERS AND MAN’S BEST FRIEND

- CHAPTER 31 CHANGES

- CHAPTER 32 AUTUMN

- CHAPTER 33 THE FINAL STRAIGHT

- COPYRIGHT

T

he car ferry whooped its hooter as we rounded the point. The ship heeled and we lurched against the others squashed into the hold as a wave of diesel-scented air blew over us from the engine room. A child at a porthole cried out that he could see the harbour, but jammed between an ancient Deutz lorry loaded with vegetables and a dented Skoda hatchback with a family of seven inside and a pile of cardboard boxes on top, we couldn’t see too much. It must have felt like this in a refugee transit camp.

‘I feel like a refugee,’ said Ivana, showing remarkable thought-reading talent and trying to smooth down her crumpled jacket. ‘Do you think I look like one?’

Not a good subject to dwell on. Ivana’s family had done their fair share of fleeing in this part of the world and I didn’t want all that stirred up again. I smiled back brightly, not wanting to admit that the last time I felt like this was standing at the school

gates on the first day of term as my parents drove off in our Morris Traveller. I started to say something suitably upbeat about British explorers, but my words were drowned out by a crashing of chains and a grinding of metal as the front of the ferry began to heave open, and we were left to our individual brands of culturally fed angst.

The angst level was already running high. This was the first day of our new life on Vis, an island thirty miles off the coast. For better or for worse we had upped sticks from London and come to live on this Croatian island. Had we done the right thing? Would it be yet another disaster like the timeshare in Andorra or the ill-fated part-ownership of the barge on the Norfolk Broads? And would we be accepted by the local community – or would we be returning to England at the end of the year with our tails between our legs?

Sunlight streamed into the hold as the bow ground open, and in front of us appeared a frenzied melée of shouting men, waving women, honking horns, weaving scooters and demented whistle-blowing. Pulling our luggage behind us, we struggled past the revving bikes and roaring lorry engines and edged towards the throng, but were halted at the gangplank. A clasping, kissing and pummelling was going on as if the ship had just arrived back from a war zone, and as those concerned seemed quite unaware that their heartfelt embracing was completely blocking the exit, it wasn’t until the whistling and shouting of two harassed policemen had broken up the family reunions that we were able to get off.

The air on the quay smelled of fish, tar, coffee, wine barrels and burned diesel. You could savour each one separately, but they mingled together quite pleasantly. Surrounded by a sea of people, all of whom seemed to know each other, we felt very conspicuous and the feeling was compounded by having to

jump smartly out of the way of small black-clad women scurrying past with cloth-covered baskets and grizzled old men pushing rickety wheelbarrows through the crowd with sharp axles sticking out like the scythes of Boadicea’s chariot. I looked around, feeling like Piglet eyeing a Heffalump trap and wishing Pooh were there to tell him what to do.

A smiling priest appeared in the crowd and, thinking he was smiling at me, I smiled back, but his beam was directed at a dog-collared passenger behind us. They bobbed up and down at each other as we were all swept forward in the melée, and from their noddings it looked as if the visitor was pulling rank on the local man, but they were swallowed up in the throng before I could get a closer look at their markings.

In front of us was a bus that seemed to have attached itself to a large metal litter bin, surrounded by a vociferous squadron of grandmothers who were shaking their sticks and umbrellas at a man in a driver’s hat. The stringy-looking fellow with a walnut of a face was standing on the steps of the bus protesting his innocence. The grandmothers, in hats of a more sensible design – though definitely not the latest fashion – had ringed the steps like Indians round a wagon train. One of them, who looked like a cross between an aged Princess Anne and a snapping turtle, was flailing at him with her walking stick while the others accompanied her sabre work with crow-like screeches.

‘It wasn’t my fault!’ the driver called out, gesticulating to the crowd with one arm while parrying the slashing granny with the other, but the granny was getting more accurate and he retreated up the steps protesting. ‘Someone moved the litter bin! How was I to know it was there?’ he cried from the safety of the bus.

The crowd was having none of it. Another matriarch, somewhat resembling an authoritative-looking sofa, came to the

front of the crowd and shouted, ‘You fool, Nano! Anyone could have seen it was there!’

Others joined in. ‘You’re as blind as a bat, Nano!’

‘Get the Town Hall to buy you some glasses!’

‘Get yourself another job!’

‘I can see a damn sight better than you can, Jako!’ the driver shouted back. ‘You’re such a short-arse, you couldn’t even see over the steering-wheel!’

The man called Jako was carrying a spade and stepped forward as if he had impromptu surgery involving Nano’s head in mind, but others restrained him.

‘You put the whole town into darkness last week when you ran over the cables, you stupid idiot!’ called a wizened octogenarian with a large white moustache, accompanying his words with appropriate gestures.

I had been learning Croatian for a few months, so had already come to know that, whereas we Anglo-Saxons tend to keep our arms by our sides and use a wide range of vocab to lend emphasis, Croatians go for the good old second language of the gesture – not that this appears to lessen the volume. Croatian is not a mellifluous tongue; not a language of love and romance. It sounds more like an angry farmer telling you to get off his mangelwurzels with lots of Zs and Xs in the words.

Looking at the front of the bus, it appeared that the driver had caught the bumper on the litter bin by taking the turn too wide. The bin, unfortunately, was made of metal and embedded in concrete. The focus of the hubbub now switched to the litter bin where a muscly young man with a sweat-soaked vest and bulging forearms was doing some virtuoso work with a metal-cutter. The crowd was urging him on and comparing him to the driver.

The adverse comparison was clearly too humiliating for poor Nano, and now that the stick-wielding granny had left off the

attack, he got down from the bus and slunk off behind a donkey cart that was standing on the quay. The donkey turned and blinked at him with the soulful eyes of a saint on an icon as Nano fished in his pocket and pulled out a pre-rolled cigarette. He lit up and took a long drag, his stringy figure outlined against the bay as he gazed philosophically out to sea. But he was not to be left to his philosophising. The stick-wielding granny spotted him and started up again. ‘He’s the most useless of all my nephews, and his father, my blessed brother, God rest his soul, was just as useless. In all his years, he could never get that sheep dip of ours to work properly, and now that stupid boy of his is making me miss my only granddaughter being given her first communion by the bishop!’

Nano’s face clearly wasn’t one that lent itself to displays of emotion, but, by the look on it now, he knew that the incident was going to be part of the fabric of village conversation for some time.

Trundling our luggage behind us, we made our way through the line of umbrella-wielding grannies and the clamouring crowd, wondering if this was a portent of things to come.

The house we had bought was at the far end of the village so we walked down the waterfront. The village was going about its business in its usual way and no one seemed in any particular hurry. Groups of women were chatting outside the shops and walking home with their shopping baskets, and, along the front, weather-beaten old gaffers sat talking on the waterside benches. In front of the houses, men were mixing cement, chipping away at blocks of stone, and chatting as they worked. Beside the sea, fishermen were mending their nets and repairing their tackle beside their gaily painted boats, and little girls in school smocks danced in between stacks of lobster pots, seemingly

unsupervised and with no barriers to keep them from falling in. We could hear the sound of banging pots and sizzling oil, and the smell of fish, garlic, coffee and herbs wafted out from the waterfront windows and hung in the air before dissipating into the breeze.

But there was something else there as well; something that wasn’t part of the world I was accustomed to, something in the way that the people went about their lives with such slow deliberation, something in the way that the old black-clad women sat by their doorsteps observing what went on. It was something timeless, human, undefinable; but it was there nonetheless.

Ten minutes later, we arrived at our courtyard and pushed the battered, green door creakingly open. Oh, Christ! The work wasn’t finished! The courtyard was a complete mess of wood, stones and rubble. Damn! We hadn’t been able to afford to do it all up in one go and had only told the builder to do stage one – the

piano nobile

– but even that wasn’t finished.

The shambles was a bit of a dampener, but as soon as we were inside it felt like home. The air buzzed with the kind of electricity generated by children in toyshops as we went from one corner of the house to the other, taking it all in – the echoing corridors, the tall Venetian windows, the smell of polished wood, the light streaming through the skylights, the sounds of the harbour percolating up over the courtyard wall. We opened the shutters and flooded the rooms with sunshine. The front windows and balcony looked out over the shimmering bay, and the French windows at the back opened onto an unkempt garden. At least the three main rooms were back to their original sixteenth-century size, and now, with the restricting walls and the hideous lino gone, the wide, dully gleaming floorboards gave a feeling of grandeur, even to the kitchen.

The unfinished work made our piles of furniture and packing

cases seem even more daunting, but the excitement gave us the strength of two Pickford’s removal men, and by midnight we had got most of the furniture into the right rooms. Then, having chosen the only bedroom with no gaping floorboards or dangling electric wires, we made up a bed, and collapsed on to it.

The next morning, I threw open the shutters. In front of me was a silvery expanse of water glittering in the sunshine ringed by green hills with fluffy white clouds in the vast blue basilica of sky above. In the courtyard below, the soft breeze ruffled the leaves of the pink mimosa and a flock of yellow butterflies fluttered around the purple bougainvillea. The only sound was a solitary fishing boat puttering across the bay and sending gentle ripples skating over the glass-like surface.

I stood at the window feeling the peace that passeth all understanding.