Under the Same Blue Sky (39 page)

Read Under the Same Blue Sky Online

Authors: Pamela Schoenewaldt

Readers Rosalind Andrews, Jessica Brockmole, Gaye Evans, and Jamie Harris provided invaluable commentary. Linda Parsons Marion graciously, tirelessly, lent a poet-editor’s eye to the final version. Doris Gove, Jo Ann Pantanizopoulos, and Odette Shults helped with listening, encouraging, and generally being there. Caitlin Hamilton Summie gives ongoing guidance.

My husband, Maurizio Conti, provides the patience, support, faith, pleasures, and good humor that keep my writing life afloat.

For lighting the way, calming, challenging, encouraging, and questioning, I am constantly grateful to my agent, Courtney Miller-Callihan. Amanda Bergeron, my indefatigable editor, brought steady insight and persistence in framing, balancing, focusing, and strengthening each draft. Finally, I’m indebted to her able team for shepherding this book through its many stages and placing it in your hands.

P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . . .*

Meet Pamela Schoenewaldt

Q&A with the Author

Gudrun’s Stollen

Reading Group Guide

Suggested Reading

Have You Read?

More by Pamela Schoenewaldt

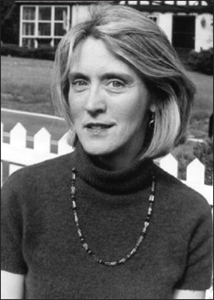

Photo by Kelly Norrell

PAMELA SCHOENEWALDT

is the

USA Today

bestselling author of

When We Were Strangers

and

Swimming in the Moon

. Both novels explore the immigrant experience, inspired by the ten years she lived in a small town outside Naples, Italy. Her short stories have appeared in literary magazines in England, France, Italy, and the United States. She taught writing for the University of Maryland, European Division and the University of Tennessee and lives in Knoxville, Tennessee, with her husband, Maurizio Conti, a physicist, and their dog, Jesse.

Discover great authors, exclusive offers, and more at

hc.com

.

Your first two novels were based in Italian immigrant communities. You lived in Italy for a time and your husband is Italian. This novel is based in a German-American community. Are there autobiographical elements in

Under the Same Blue Sky?

Actually yes, perhaps more than in either

When We Were Strangers

or

Swimming in the Moon

. Like Johannes and Katarina Renner, my paternal grandmother, Caroline, was born in Heidelberg. She came to America at age four with her adoptive parents. By all accounts they provided a stable, loving, happy home. However, like Hazel, the fact of my grandmother’s adoption was kept hidden, and her memories of another life were dismissed as dreams. It was not until her forties that a chance comment by a family friend unraveled the truth. In the aftershock, she created for herself a romantic identity story: her mother was a servant in a noble household; her father was the titled heir. He died young, her story went, and the distraught mother gave the child to emigrating friends with the idea of saving money, following them to America, and retrieving the child. Then, the story continued, the mother came over, searched for her daughter, never found her, and died tragically, alone. That there was scant historical evidence for any of this didn’t stop me from having my own fantasy that one day my noble family

would come to save me from my prosaic New Jersey life and its onerous tasks (cleaning my room, loading the dishwasher, and so forth). They would whisk me to the splendid castle and gilded life which was my bloodright. Sigh. That never happened. But you’ll see parts of the story in

Under the Same Blue Sky

.

In a more general sense, in framing Hazel’s home life, I drew from my own childhood and what I perceived as German-American values that “went without saying”: studying hard, doing homework, respecting teachers, being on time, never ever addressing adults by their first names, avoiding “bad company” and “trivial entertainments,” being frugal, not wasting food, avoiding debt, doing respectable (i.e., professional) work. While constricting at times, this net of expectations gave a certain security to me and to Hazel, even when she broke out of the net.

Your fictional town of Dogwood, New Jersey, houses a baron’s castle. Where did that idea come from?

I went to high school in Watchung, New Jersey, which at that time housed an actual castle built in 1900 by the Danish Moldenke family, whose line could be traced back to the Crusades. With forty rooms, medieval arms, vast library, and a mausoleum, the Moldenke castle was rich ground for local fables. In 1945, it passed to a biologist of less storied family, and the original Danish owners were forgotten. Locals invented instead a German nobleman who built the castle for his homesick princess bride. By the time I was nosing around the castle grounds with friends, we had morphed the biologist into a mad physicist who did evil experiments in his laboratory. Digression: Why always “mad physicist,” and not “mad civil engineer” or “mad ichthyologist” or “mad accountant”? Being married to a not-mad physicist, this question troubles me. Back to Watchung. Eventually the biologist moved away, and no buyer could be found. The castle was steadily vandalized, then sold to a developer, burned under suspicious circumstances, and was soon after bulldozed to make way for unromantic McMansions. But the image of turrets visible from school bus windows stayed with me all this time and now has a new life in fiction.

You describe very vividly the situation of German-Americans during World War I. While propaganda vilifying the enemy is typical in wartime, what made the German-American situation at this time unique?

German-Americans are the largest self-reported ancestry group in the United States. Between 1880 and 1890, there were nearly 1.5 million German immigrants. By 1900, more than 40 percent of the residents of Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati were German-born. Many smaller midwestern communities had far higher percentages. German-Americans could be found in every social strata and profession. This fact undoubtedly helped maintain American neutrality far into World War I, bolstered by general resistance to “foreign entanglements,” and, as Hazel saw, the incredible profit in selling arms to belligerents without donating soldiers to the cause.

As pressures for war built, German-Americans who felt emotionally bound to their country and culture of origin tried desperately to reconcile conflicting loyalties. One way of contextualizing this conflict was the widely used phrase “Germany is our mother, America our wife.” I don’t know how convincing or comfortable the phrase was to anybody. For some, like Hazel’s father, the strain of equal and opposite pulls was truly unbearable.

President Woodrow Wilson, who argued for neutrality as long as possible, warned: “Once lead this people into war and they will forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance.” When the United States joined the Allies in April 1917, overnight the homeland of millions of Americans became the evil empire, the land of Huns. Former neighbors, friends, and colleagues were suddenly potential enemies or spies. An enormous propaganda machine sprang up. As Hazel reports, standard English had to be purged of German words with ludicrous results, like changing dachshunds and German measles into “liberty pups” and “liberty measles.” That was the light side. There were lynchings, beatings, homes and businesses destroyed. Many lost their jobs; families were divided; peaceful communities were ripped apart. Everywhere, for

every

American, the

Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Amendment of 1918 trampled civil rights, free speech, freedom of the press, and free assembly.

While clearly these effects were later overshadowed by the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II, the Holocaust, and ethnic wars that claimed and still claim millions of lives, President Wilson has been proved right: war is never just “out there” on the battlefield. The tolerance that binds and enriches a civil society is ripped away by war as we take its conflicts into our communities, our neighborhoods, and our hearts.

Was your family in the United States during World War I, and if so, what was their experience?

My family was here, but I only know one story. My maternal great-grandmother was sent over from Germany to Iowa in the late 1800s to marry her brother’s friend. (I called on this fact in my first novel,

When We Were Strangers

). By the time the United States entered World War I, she had learned English. Her husband, a dour and antisocial fellow, never did. A new ruling in their little town outlawed speaking German in public. That was fine with my great-grandmother. She’d fallen in love with her new country. When her husband announced that he’d never speak English, her response was: “Suit yourself. But nobody will talk to you.” Apparently, that didn’t bother him.

Ben Robinson and Tom Jamison struggle with what was once called “shell shock” and is now termed post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. Like so many families today, Hazel, Tom, and David must deal with the invisible wounds of war. What did you discover as you researched this phenomenon?

Within months after the start of World War I, armies on both sides faced an epidemic of massive proportions. With no apparent physical injury, officers and enlisted men were presenting a confounding range of symptoms: panic, almost infantile helplessness, extreme lack of coordination, mutism,

hysterical blindness, bizarre gaits and facial tics, amnesia, fugue states, headaches, uncontrollable tremors, hypersensitivity to sound, rigidity, and incapacitating fixation on traumatic events. Strangely, officers were five to eight times more vulnerable than enlisted soldiers. Everywhere, the fighting force was endangered. No other war had produced these effects on this scale. Generals, politicians, and the medical community struggled to find a cause and a cure as the epidemic raged, producing casualties as high as 40 percent in some units.

In 1915, the term

shell shock

was coined by British researcher Charles Myers, assuming that the cause of these strange behaviors was neurological damage caused by passing shells. This proved false, since troops far from the front were stricken as well. However, the name stuck. Some blamed lack of moral fiber, cowardice, and simply faking symptoms to avoid combat. Suggested cures included denial, humiliation, physical punishment, and electric shocks to have victims buck up and return to the trenches. More compassionate approaches were tried and sometimes succeeded, but the sheer mass of casualties overwhelmed resources in every army. For a wrenching description of the “boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk,” see “The Survivors” by Siegfried Sassoon, one of the great British war poets.

Many turned to the new field of psychoanalysis for explanation. Ernest Jones, a British doctor who worked closely with Sigmund Freud, blamed this new kind of war, unequaled in the savagery and trench conditions that soldiers endured, forcing them to “indulge in behaviour of a kind that is throughout abhorrent to the civilised mind. . . . All sorts of previously forbidden and hidden impulses, cruel, sadistic, murderous and so on, are stirred to greater activity.” The unbearable inner conflict between these dark impulses and the civilized mind, Jones concluded, inevitably produced bizarre behaviors.

The Freudian analysis has been debated and refined. Other theories have been proposed. In the past century, enormous energy has gone into prevention, identification, and management of what we now call PTSD in military and civilian life. We have

certainly progressed in compassion and therapeutic options, but still many survivors and families suffer. Like those who return with shrapnel deeply embedded in the flesh, PTSD rarely just goes away. Yet the loving and patient support that Tom finds in Galway (even without the magical powers of a blue house) can ease symptoms and uncover ways to negotiate a new normal. Considering the horrific scenes and situations to which we subject our soldier-agents, this in itself is nothing short of miraculous.