Unknown

Authors: Unknown

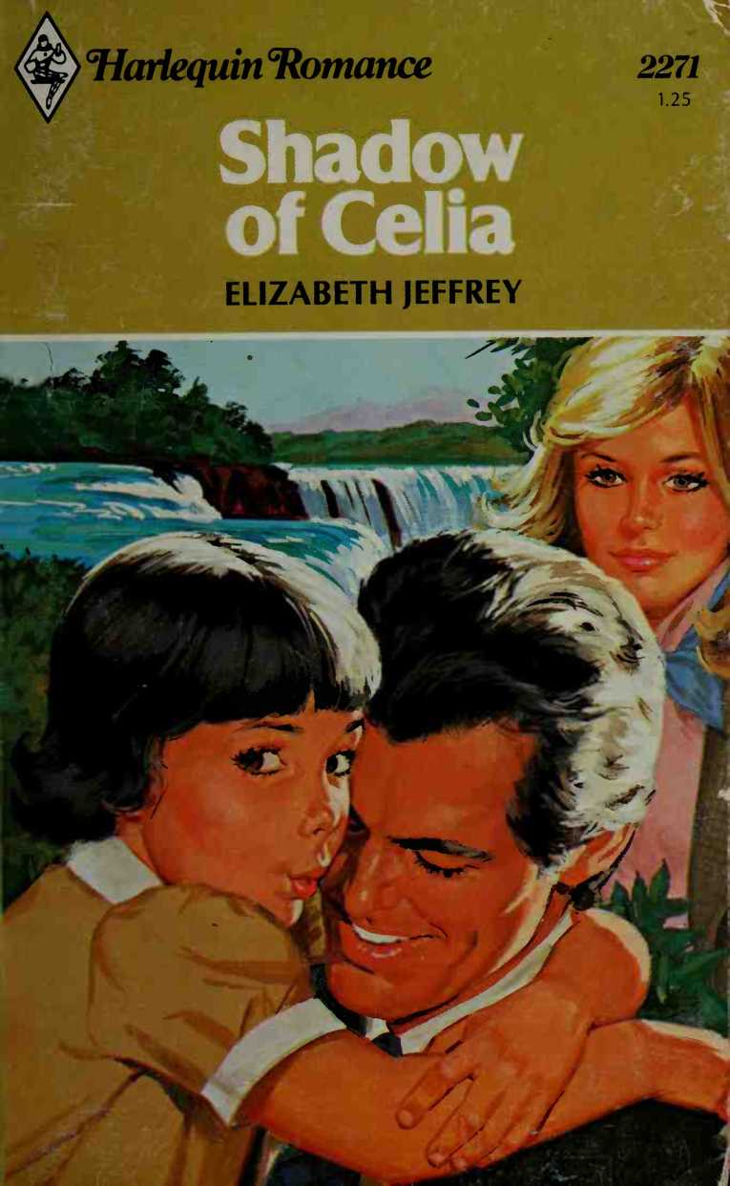

SHADOW OF CELIA

Elizabeth Jeffrey

Could she compete with a memory?

After her fiancé's death, Rachel had gone to Scotland to try to pick up the threads of her life.

Once there, however, her life became tangled with the lives of two others—an elfin-faced child who refused to speak after the tragic loss of her mother; and the ill-fated husband who must have truly adored his wife.

As governess, Rachel thought she could help Melanie. But there was nothing she could do for Richard Duncan, except fall in love with him!

"Thanks for coming to my rescue."

Rachel's voice was warm with gratitude. Impulsively she moved closer to Richard. "I don't know what I would have done without you."

"I think," Richard said slowly, "I'm entitled to a little more than a mere thank you. I noticed the other day at Eilean Dorcha that you were being quite friendly toward Ben Carson. What's good enough for him can't be bad for …me."

Swiftly he caught her to him, almost crushing her with the strength of his arms as his mouth came down on hers. For a moment she was powerless to move, then the implication of his words hit her.

Furiously she brought up her hand and gave him a stinging blow on the cheek. "How dare you!" she raged.

It

was still raining when the boat docked at Dunglevin. Cars and people began spilling off, so Rachel Canfield picked up her suitcase, put up her umbrella and followed the crowd. With her blonde hair hanging straight and shining to her shoulders she was a slightly taller-than-average girl, trim-figured in a navy trouser suit and brightly coloured blouse. Attractive without being pretty, her bone structure was good but her nose was just a shade too long and her mouth just a shade too wide for beauty. Her eyes, though, were quite lovely, large and a deep violet. On close inspection, however, they held a look of suffering that went far beyond her twenty-four years.

‘The buses for Glencarrick?' she enquired of the man who took her ticket. He was thick-set, with receding grey hair and bad feet.

‘Twice a week. Tuesdays and Fridays.’

‘But this is Wednesday!' Rachel's heart sank to her knees.

The man shrugged.

‘How far is it, then? Can I walk?’

He looked down at her platform shoes and his expression was eloquent.

‘Ye might. In aboot three days. Glencarrick’s thirty miles from here.’

‘Oh.’ Rachel’s heart sank from her knees to the ground. She pushed a strand of damp hair away from her face. This was all she needed! She turned away with a sigh. She had never wanted to come to Scotland in the first place, but her father had insisted on writing to his sister—whom Rachel had never met—telling her of Keith’s tragic death and Rachel’s subsequent breakdown and suggesting that a change of scenery might be helpful. Her aunt’s reply had been prompt and welcoming, but it was more to please her parents than anything that Rachel had agreed to the visit. Now that she no longer had Keith it made little difference to her where she was or what she did. Life had lost all meaning for her six months ago. She began to walk along the pier towards the road, hardly aware of what she was doing, her mind back on that terrible evening when they had come to tell her that Keith, the young solicitor she was to have married in less than a month, had been killed when his plane crashed on the way home from a business trip to Germany. Even now, desolation swept over her as she remembered that night, and the tears—after all these months still never very far from the surface— welled up in her eyes.

‘Are you the young lady who’s anxious to get to Glencarrick?’

Rachel looked up mistily and was aware of a tall man in his early thirties, with a deep, pleasant voice which altered impatiently as he said, ‘Oh, heavens, you’re surely not weeping because there isn’t a bus!'

She sniffed and pulled herself together. ‘Certainly not,’ she said icily. ‘A piece of grit got in my eye, if you must know. I was just about to call a taxi, although I can’t see that it’s any business of yours.’ She turned her back and bent to pick up her suitcase.

It was taken from her grasp. ‘There’s no need. I’m going that way myself, I’ll give you a lift. Kilfinan Cottage?’

Rachel looked at him in amazement. ‘How did you know that?’

‘The Glen is sparsely populated, so news spreads pretty quickly. You’ll be Rose’s niece.’ It was a statement, not. a question, so Rachel decided it didn’t need an answer. Relieved to have transport, although she didn’t care much for the man himself, she followed him to the Range Rover parked nearby and waited while he stowed her suitcase, then she climbed in beside him, stealing a glance at his profile as she did so. Re wasn’t exactly good-looking; striking would be a more accurate description. His face was long, his nose slightly aquiline, his jaw firm to the point of sternness. His eyes, behind the heavy glasses he wore for driving, were deep-set and very dark. In fact everything about him was dark; his hair was thick, slightly curling and jet black, he wore a black roll-neck sweater, even his skin was dark—brown and weatherbeaten. He looked lean and athletic, as if most of his time was spent out of doors and his hands on the steering wheel were strong, square, and capable. He handled the Range Rover with complete assurance.

They drove in silence out of the town and along narrow roads that curled their way between mountains that looked like gigantic black bonfires where the rain-clouds smouldered over them. Clutches of soggy sheep grouped spasmodically along the way watched balefully as they passed.

'It doesn’t always rain like this,’ he volunteered at last, ‘although I must admit that we do get more than our fair share in these parts.'

‘It makes no difference to me what the weather is like.’ Rachel was tired after the journey, but even so she hadn’t intended to let her voice sound quite so flat.

He turned his head and his eyes met hers. They were totally unsympathetic. ‘Yes, we’ve heard about your

unfortunate affair. I’m sorry. But these things happen, you know; you can't live in the past.’ He turned his attention back to the road, which was now climbing steeply by the side of a loch.

Rachel opened her mouth to reply, but no words would come. Who was this man? What right had he to speak to her in such a callous manner? And how was it that he knew so much about her? Was Aunt Rose, about whom she knew so little, nothing more than a gossipy old woman who couldn't keep her affairs to herself? Rachel frowned. She knew nothing about her father’s sister, except that she was unmarried and had kept house for Alistair Duncan, an elderly man who lived at Kilfinan House, for the past thirty years. Suddenly Rachel realised what a fool she had been. It was only to please her father that she had agreed to visit this aunt; now here she was, in a godforsaken spot miles from anywhere, where the rain fell in relentless icy needles and where, it would seem, you couldn’t call your soul your own. She had come all this distance to try and forget what had happened—how her life, so full of hope and promise, had been so suddenly and cruelly shattered. Instead of which, the first person she met knew of her tragedy and wasted no time in reminding her of it. Clearly, it had been a mistake ever to have come here.

Seething inside, she turned to him. ‘Would you stop the car, please.’ It was not too late. She could stay in an hotel in Dunglevin tonight and return to her home in Suffolk tomorrow.

The road was still climbing upwards. It appeared to have been carved out of the side of the mountain which rose, steep and craggy to one side, while on the other side it fell away to the loch below, guarded, but only where the road bent sharply or the drop was precipitous, by a crash barrier.

Since the man beside her appeared not to have heard, Rachel repeated her question.

‘I heard you the first time

:

but don’t you realise that you can’t stop willy-nilly on roads like these? You’ll have to wait until we come to a passing place,’ he replied shortly. ‘There’s one a little way ahead. Ah, here we are.’ He pulled into a fairly wide parking area, built out over a natural bulge in the mountainside and parked, it seemed to Rachel, who had no head for heights, precariously near to the edge. The rain still drummed unmercifully on the roof of the car and ran in rivulets down the windscreen, too fast for the wipers to cope with. Her companion leaned on the steering wheel and gazed at her. ‘Well, what are you intending to do, get. out and walk?’ he asked. ‘Before you do, perhaps you should know that we’re well over half way to Glencarrick now, so you’ve a long trek back to Dunglevin. It’s a bit damp out there, too, and you’re not really dressed for it. Still, it’s up to you—and if you do get out and walk spare a glance for the view, it’s one of the finest in these parts. But make up your mind, because I want my tea.’ He spoke in a completely matter-of-fact tone that infuriated Rachel even further.

Savagely, she pushed open the car door, but the force of the wind and rain blew it shut again before she had a chance to get out.

‘I thought you’d see sense.’ Before she had time to open it again the man beside her had let up the clutch and the car had begun to move again. Humiliated, Rachel huddled in her seat, not speaking, for the rest of the journey, which took them down the mountain road, through the little fishing town at its foot and then inland to Glencarrick, where the clachan, or village, nestled in a hollow and Kilanan House, sitting squarely on the lower slopes of the mountainside, commanded a view of the entire glen. In spite of the rain, in spite of her unprepossessing introduction to the area, indeed, in spite of herself, Rachel couldn’t help being impressed by the sight of the big white house set among the trees.

At the lodge gates the man stopped the car. ‘This is your destination,’ he said, getting out and reaching for her suitcase. ‘No doubt Rose will have the kettle on.'

Rachel doubted if he heard her grudging words of thanks as he climbed back into the Range Rover and drove off down the glen. She still had no idea who he was, and she didn't much care. She simply hoped she wouldn’t see him again.

Aunt Rose greeted her cordially enough, although she was obviously surprised to see her. Rachel could see no family likeness in her aunt; she was a tiny woman, very thin, her face sallow and lined. And it didn’t help her rather stern appearance that she wore her hair, dark and streaked with grey, dragged back into an uncompromising knot.

‘How did you get here? There are no buses,' Her aunt’s voice was unexpectedly low and well-modulated. ‘I’d arranged for Ben to meet you in Dunglevin tomorrow. I wasn’t expecting you until the twenty-second, you see.'

‘But this

is

the twenty-second,’ Rachel said, adding uncertainly, ‘isn’t it?’

‘No, tomorrow’s the twenty-second.’ Rose patted her arm. ‘But no matter, my girl, you’re here now and I’m pleased to see you. Someone gave you a lift?’

‘Yes.’ Rachel didn’t elaborate on her rather uncomfortable encounter.

Rose nodded. ‘People are very good in that way around here. Now, draw up to the fire while I set the table. Oh, this is Melanie, by the way, Mr Duncan’s granddaughter. She spends quite a lot of time here with me when she’s not roaming with Ben.’ Rose nodded towards the corner, where a little girl of about six was curled in an armchair. She was a pretty child, or would have been had it not been for the strange, almost hunted look that she wore. She had thick black hair, cut in a low fringe, and pale, elfin face. She was staring into the fire with enormous brown eyes, apparently oblivious of Rachel’s entrance.

‘Hullo, Melanie,’ Rachel said with a smile, but the child paid no attention and continued staring into the fire.

‘She won’t talk to you. She doesn’t talk to anyone,’ Aunt Rose explained. ‘Take no notice.’ She was busy laying the table with home-made scones and oatcakes as she spoke.

Rachel warmed herself gratefully at the fire. Despite the fact that it was late June the rain had chilled her to the bone and she felt herself shivering, mainly with cold but partly with apprehension. Her welcome to Scotland had not been altogether overwhelming, so far.

As she warmed herself she could feel Melanie’s eyes on her and with a smile she turned to look at the child. Immediately, the big brown eyes were averted and the child seemed to shrink back even further into the corner of the armchair.

‘She needs the company of other children. She’s alone too much,’ Rose said, pouring out tea.

‘Doesn’t she meet other children at school?’

‘She doesn’t go to school. They tried her at the local school, but it didn’t work; in fact, it made her worse than ever. Her father wants to send her away to school, but Mr Duncan wants to have a governess for her. He says she’s had enough upheavals in her life without adding more. He’s right, too.’

Rachel was puzzled. Her aunt was talking in riddles. Talking about Melanie, too, as if the child wasn’t present.

‘Come along, Melanie. On your chair,’ said Rose.

Obediently, the little girl slid from her armchair to her chair at the table and began to eat the scone that Rose had placed before her. At least, Rachel reflected, there was nothing wrong with the child’s hearing.