Untying the Knot: John Mark Byers and the West Memphis Three (27 page)

Read Untying the Knot: John Mark Byers and the West Memphis Three Online

Authors: Greg Day

Tags: #Chuck617, #Kickass.to

Damien’s sister, Michelle and her daughter Stormy outside the Arkansas State Supreme Court September 30, 2010. Michelle has not seen her brother in many years, and not at all since his release from prison. Stormy wasn’t born when her infamous uncle was arrested and has only met him once when she was very young.

“This is a travesty!” John Mark Byers was on hand in Jonesboro the day the West Memphis Three were released. He was furious that Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley had to plead guilty to murdering his son in order to be freed from prison.

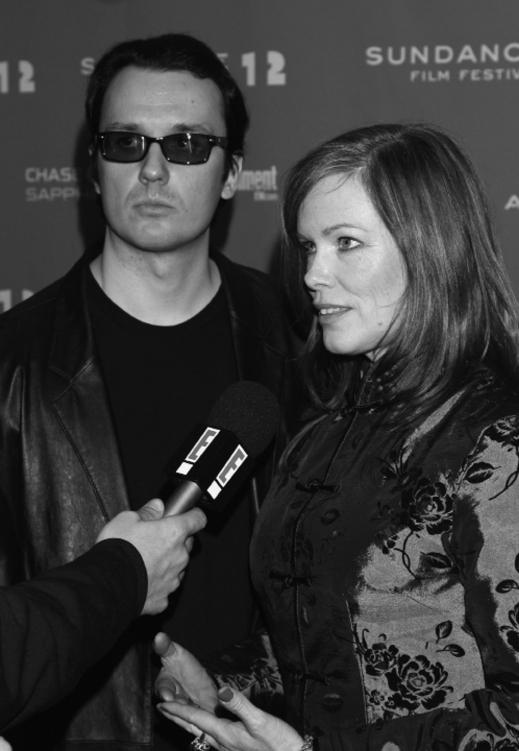

Damien Echols and wife Lorri Davis at the premier of

West of Memphis

at Sundance in 2012. The film was backed by Sir Peter Jackson (

Lord of the Rings

), directed by Amy Berg (

Deliver Us from Evil

), and produced by Echols and Davis. In many ways the film overshadowed the concurrent release of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofky’s

Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory

.

Mark finally greets Damien Echols at Sundance, the first time Mark has actually seen him since the Rule 37 hearings in 1999.

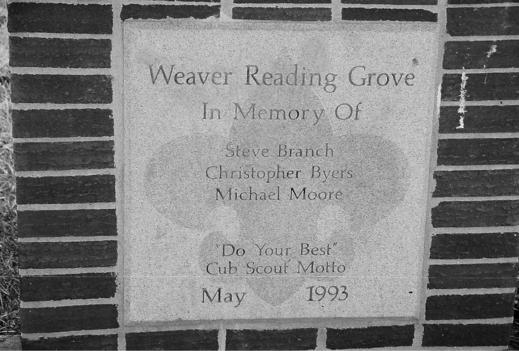

Weaver Elementary School Memorial Reading Grove. The commemoration on the plaque is heart wrenching in its brevity. “Do your Best.” Their memory has often taken a back seat in the effort to Free the West Memphis Three

Justice

is

the

constant

and

perpetual

will

to

allot

to

every

man

his

due.

—Domitus Ulpian, Roman jurist (100-228 CE)

Prison

saved

my

life

.

—

John Mark Byers

By the end of 1998, Mark Byers’s life was teetering precariously on the verge of collapse. He was living alone in a small rented apartment with nothing but his thoughts. In many ways, he had not been allowed to move normally through the grieving process. The film

Paradise

Lost

not only had made life difficult for Mark in and around Jonesboro, but its not-so-subtle innuendo regarding his possible complicity in the murders had left him an emotional mess as well. Melissa was gone, Ryan was gone, and his family was left to helplessly watch him deteriorate mentally, emotionally, and physically. Unable to cope with the past and what had become of his life, he tried, without much success, to deaden the pain with pills, booze, and pot. If he could just feel

nothing

, that would be better than what was happening inside him. His trip to rehab in 1996, along with all the medication that had been prescribed to him upon his release, had temporarily relieved any overt suicidal tendencies along with the crippling depression symptoms he’d been suffering. Left in the place of such feelings, however, was a hollow, emotional void, interrupted by periods of blatant self-destructive behavior. From day to day, and in between disability checks, Mark Byers simply existed.

Things in Jonesboro had become very monotonous. By 1997 Mark had lost his car and driver’s license, and his world suddenly became very small. He walked everywhere he went, and aside from the time he spent hanging out with James Lawrence in Marked Tree, there wasn’t a thing going on in his life. His stay in rehab had come only six months after the release of

Paradise

Lost

and only three months after moving from Cherokee Village, and after his release from the George W. Jackson center, he had quickly resumed the booze, pill, and pot lifestyle he had been living prior to his stay there.

121

If people didn’t recognize Mark from the extensive TV and newspaper coverage of the trials—the Echols/Baldwin trial had been held in Jonesboro, after all—they were sure to spot him after the premiere of the HBO film. The repercussions of his prominent role in the documentary were varied and sometimes violent. Once, while visiting a “private club” across the street from his apartment, Mark was attacked in the men’s room by four men ranging in age from late teens to early twenties. “We know who you are,” one said just as Mark was backing away from the urinal. “You’re that baby killer.”

122

Without further warning, two of the men landed sucker-punches to Mark’s head and face, dropping him to the bathroom floor. When he came to, the men were gone, but upon a quick survey of the club, he found two of them hanging around shooting pool. Grabbing a pool cue off the wall, Mark hotly strode toward the table. Before he got there, however, two bouncers collared him and dragged him to the door. By this time his eye was swelling shut, and his split lip was bleeding profusely down the front of his shirt. The police were called, but by then the attackers were gone.

Without a car, Mark had little hope of getting a job, though it is questionable how successful he would have been at maintaining any kind of steady employment. He had also completely lost touch with Ryan and was virtually alone, and when Mark was alone, he “self-medicated.” It was in this zombie-like semiconscious state that Mark participated in the filming of

Revelations:

Paradise

Lost

2

. To be sure, there were periods of lucidity, and these can be seen in the film. Appearing in front of his Stone Street efficiency, decked out in his signature American flag shirt, Mark is clear-eyed and coherent. A scene filmed inside his apartment, as he hangs out with friends Willie Burns and James Lawrence, reveals a Mark Byers arguably in control of himself. In other scenes—the confrontation with the Free the West Memphis Three organizers on the courthouse steps, for example—he appears bloated and puffy-eyed, slurring his speech and mixing up his words. In October 1998, during the first round of Damien Echols’s Rule 37 hearings, Mark was filmed on the sidewalks of Jonesboro, his eyes bleary and stance unsteady, as Echols was led into the courthouse. “You ain’t goin’ to be no boogeyman in West Memphis,” he slurred, “’cause you’re goin’ to be dead in

hell

!” At this, he cocked his thumb and forefinger in a mock-shooting pose, pointing straight at Echols. His posture, despite his hulking form, was somehow weak, unbalanced. He was bloated from months of poor nutrition, heavy drinking, and drug use.

Mark has often been described as “scary.” To those who knew him well, he looked pitiful at this point. The contrast between his physical appearance six months earlier, when he was filmed singing at the table in his Jonesboro studio apartment, and that of the haggard inebriate at the Rule 37 hearing is startling.

123

He seemed unaware at this point that he was being set up. “They keep wantin’ to find someone else to blame to get their three off. That’s their job. Draw suspicion, do their thing,” he told a reporter on camera. “But the world knows who’s guilty and who’s innocent.” By now, Mark was well aware that the suspicions they were “drawing” were aimed squarely at him. The knowing glances between Kathy Bakken and Burk Sauls as Mark strode off toward the courthouse after a somewhat heated on-camera exchange provide some evidence that

they

knew as well. It didn’t matter. If Mark was aware of what was happening, he probably would have waded right in anyway, as he has done so often, like a prize-fighter in the late rounds after taking one too many punches.

By the time Creative Thinking International and HBO Productions packed up and rolled out of Arkansas, and the last of the Rule 37 hearings wound down in March 1999, Mark had gotten himself into a world of trouble. His depression had returned. His lifelong friend James Lawrence had died in 1998. He saw his family only sporadically; it was difficult for them to watch him fall apart. “My brother says today that [the family] was just waiting to hear that I was dead,” Mark recalls.

In August 1998, after sitting by the side of the road, “waiting for an eighteen-wheeler” and contemplating suicide, Mark once again checked himself in for medical treatment, this time at St. Bernard’s Behavioral Health Center in Jonesboro. He was again diagnosed with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, and alcohol dependence, which at the time he denied. According to his doctors, he “became angry and threatened the physician” when substance abuse treatment was recommended. At the time he was admitted, he was taking many prescription medications, including Zoloft and trazadone (for depression), Depakote (for seizures related to his brain tumor), Xanax (for anxiety), and propranolol (for migraines and anxiety). The doctors took note of his medical history, which included a right frontal lobe brain tumor, a seizure disorder, a hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal (GE) reflux, and “chronic losses”—the deaths of family and friends.

124

Not surprisingly, they attributed his depressed state to those factors, as well as to alcohol abuse. They also noted a “facial asymmetry” and “abnormal gait” and recommended a repeat CT scan.

Mark “continued to remain on the outer fringe of the therapeutic milieu [group therapy],” according to his doctors, and was “not engaging in treatment initially, continuing to be distractible.” The reasons for this were apparent: “[Mark] did continue to ruminate over the death of his son, and voiced resentment and anger toward the individuals who murdered his son.” His contemplation of suicide suggests the truth of what is said of grieving parents: they don’t choose to live; they just don’t choose to die.

125

The doctors noted with some satisfaction that toward the end of his treatment, Mark was beginning to “process his grief issues.” On August 9, 1998, after a few medication adjustments and two weeks of therapy, Mark was discharged. He was given a lengthy list of prescriptions to fill, including Xanax, Depakote, Gabitril (seizures), Pepcid (GE reflux), Inderal (headaches), Vicodin (headaches), Desyrel (insomnia), and Zoloft. He was instructed to have magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) testing done on both his brain and neck as an outpatient. He was also instructed to attend Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings nightly for “aftercare and support treatment.” But he “left rehab, went straight to the drugstore, got [his] prescriptions filled, and bought a six-pack of beer at the Stop ’n’ Go,” Mark said. “I went home, drank the six-pack, ate a hand full of pills, smoked a big, fat joint, and never looked back.”

Paying

the

Piper

For all the bullets he took, Mark had unquestionably dodged his share too. As noted earlier, shortly after graduating jewelry school, he had been arrested in Louisiana for possession of marijuana. The evidence “disappeared” before trial, and he was more or less forced to flee the state. His 1987 arrest and conviction for the terroristic threatening of Sandra Sloane resulted in his being placed on probation for three years. Although this was a misdemeanor charge, a violation of the probation could have resulted in up to a year of imprisonment. The 1992 Rolex watch incident could—and some would say should—have led to felony charges, had the district attorney decided to prosecute.

126

There was also the botched 1992 sting operation where Mark briefly faced federal drug and weapons charges, from which a ten—to twenty-year prison sentence easily could have resulted. In February 1993, just three months prior to Christopher’s murder, Mark was arrested after police seized a pound of marijuana from the trunk of his car. He had a court date set, but after Christopher’s murder, the local prosecutor dropped the charges without explanation. And of course, there were the original convictions for residential burglary, theft of property, and contributing to the delinquency of a minor in Sharp County in 1996, which earned him two concurrent five-year sentences and one twelve-month sentence—all suspended—and banishment from the Arkansas Third Judicial District. These last three convictions were what eventually became his undoing.

Wrong

Number

The events of January 9, 1999—like those of May 5, 1993, and March 29, 1996—drove home to Mark just how quickly and profoundly life can change. For all his misdeeds and all the slippery slopes he had negotiated, his downfall came not from any coordinated police action or as the result of a targeted criminal investigation, but by his own hand or, more accurately, his fingers. Many of the details of his arrest in Jonesboro on that winter’s day are drawn directly from the police reports. For his part, Mark doesn’t remember exactly what happened. “It

could

have gone down that way,” he said when first asked about the incident. “I’m not saying it didn’t. I’m just saying I’m not sure.”

Earlier on that chilly Saturday, Mark had sold twenty of his prescription Xanax pills to a friend of a friend, Leon Burgess,

*****

for three dollars each. All of Mark’s income at the time was coming from his disability check, so selling his prescriptions brought in cash, though there is evidence that this instance was simply intended to be an exchange of drugs; Mark was selling his Xanax in order to buy some marijuana. Apparently, Leon had not paid the full sixty dollars for his purchase that morning because at around five o’clock in the afternoon, Mark called the young man on his cell phone and reminded him of his debt and also asked if he wanted to buy the remaining twenty pills.

127

There was a problem, however. The number that Mark dialed was off by one digit. Instead of calling Leon, he had dialed the cell phone of Arkansas state trooper Brent Tosh, who was on duty and in the middle of a routine traffic stop when he received the call. Tosh told Mark that he would have to call him back. He took Mark’s phone number and immediately called Sergeant Roger Vickers at the Arkansas State Police, Troop C, to see if he could do a reverse lookup on the phone number to get an address.

128

When Vickers told Tosh that he could not perform such a lookup, Tosh called Mark back.