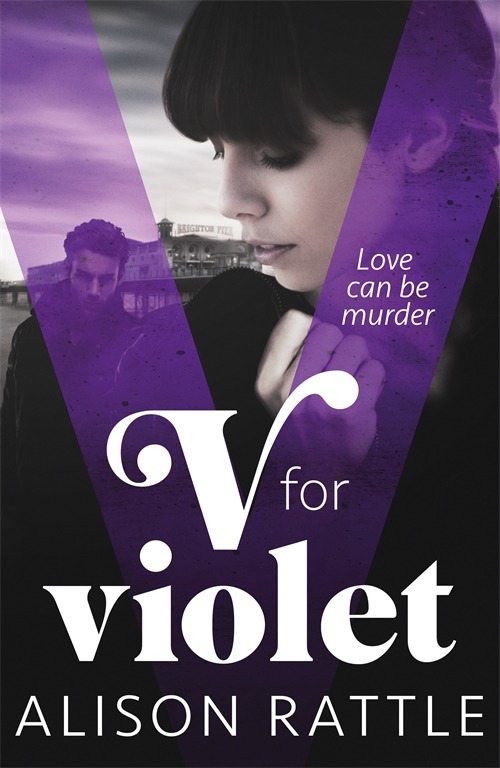

V for Violet

Authors: Alison Rattle

Contents

Down in a green and shady bed,

A modest violet grew;

Its stalk was bent, it hung its head,

As if to hide from view.

And yet it was a lovely flower,

Its colours bright and fair;

It might have graced a rosy bower,

Instead of hiding there.

– Jane Taylor

I was born above our fish and chip shop on Battersea Park Road, at the exact moment Winston Churchill came on the wireless to announce the war was over.

Nobody saw me come into the world. Nobody saw me land on the newspapers that had been laid out under Mum’s bottom and across the mattress to protect it from stains. Even Mum missed my birth, she was so busy cheering along with the rest of them. The rest of them being my dad (Frank the Fish), Mrs Rice the midwife, my sister Norma and a motley collection of neighbours who’d come in to listen to Mr Churchill, because they didn’t have a wireless of their own. Mum had insisted on taking the wireless into the bedroom with her when the first pains started, so of course it stood to reason that everyone else crowded in there too.

It was a while before anyone saw me lying there, all goggle-eyed and gasping for air. ‘Never felt a thing!’ Mum said, when Mrs Rice finally turned her attention back to the goings on between Mum’s legs and exclaimed out loud at the sight of me floundering around on the bloodied pages of the

Evening Standard.

Violet, they called me.

V for Violet

V for Victory

Most people don’t remember the moment of their birth. But I’ll never forget it. One minute I’m cocooned in a delicious warm, safe darkness, dreaming of nothing in particular. The next, I am being squeezed so tightly that my soft little ribs pop. Then the shock of cold and wetness and a terrible burning as my first breath inflates the delicate tissue of my lungs. Then white, aching light and the stink of stale fat and newspaper print (although I couldn’t have put names to the things I was smelling then, of course).

Once my eyes had blinked a few times and got used to the new sensation of brightness, I looked around. And there they all were; blurry faces turned towards the small box on the dressing table.

Advance Britannia

Long live the cause of justice

God save the King

Those were the first words that crackled down the tiny coils of my newly unfurled ears. The voice of the British Bulldog. I’m lucky they called me Violet. They could have given me a really stupid name, like Winnie or something.

Anyway, there I was, a tiny pink creature, star-fished in the middle of the bed, blinking and breathing and waiting for somebody to pick me up and love me.

There’s a photograph standing pride of place on the mantelpiece in our front room. Mum dusts it religiously every day. The frame is an ugly, heavy thing, made from carved oak. It reminds me of the coffin they buried our neighbour Mr Dennis in last year. Which is quite funny really, because the face staring out from the centre of the ‘coffin frame’ is of a dead person too.

It’s my brother Joseph. He looks like a proper bobby dazzler all done up in his battledress. The collar of his jacket is buttoned tight around his neck and his cap is balanced very dashingly on the side of his head.

He looks as though he is swallowing a smile; trying to be all serious when really he just wants to fool around. In the photograph, Joseph is only nineteen. There’s the trace of a pale moustache along his top lip and twinkling stars in his eyes

I never met him. He went missing in action before I was even born. Norma told me once that no one had ever heard a scream like the one that came out of Mum’s mouth on the day the telegram was delivered. It was like her soul had been ripped from her insides, Norma said. But then Norma has always been prone to dramatics.

The telegram is on the mantelpiece too, in a tortoiseshell frame. I remember when I was younger I used to worry about the poor tortoise who had been robbed of its home so its shell could be cut up and polished and stuck up there on our mantelpiece. I asked Norma to teach me to knit so I could make little blankets for all the naked tortoises so at least they would be warm at night. ‘You really are a ninny, Violet,’ she said to me. ‘Only you would think of such a thing.’

When I got older and learned to read, I forgot about naked tortoises. Instead, every time I read the telegram my tummy went all squirmy. At first, I thought it was sadness making me feel like that. But as I got older, I realised the feeling was something much worse.

From Wing Commander D. A. Garner

Royal Air Force Station

Kirmington

Lincolnshire

4th August 1944

Dear Mr and Mrs White

May I be permitted to express my own and the squadron’s sincere sympathy with you in the sad news concerning your son Sergeant Joseph White.

The aircraft of which he was the Flight Engineer took off to attack Trossy St. Maximin Constructional Works, near Paris, on the 3rd August 1944, and nothing further has been heard.

You may be aware that in quite a large percentage of cases aircrew reported missing are eventually reported prisoners of war, and I hope that this may give you some comfort in your anxiety.

Your son was a most proficient Flight Engineer and his loss is deeply regretted by us all.

Your son’s effects have been collected and will be forwarded to you in due course through Air Ministry channels.

Once again please accept the deep sympathy of us all, and let us hope that we may soon have some good news of the safety of your son.

Yours very sincerely

Donald A. Garner

Mum talks about Joseph every day. Even though it’s been over sixteen years since he went missing. When she picks up his photograph she always breathes on the glass first before she polishes it with her cloth. Then she kisses the glass, right where his face is, and the ghost of her lips blurs his features. I don’t know why she bothers to polish it at all.

Mum reckons that Joseph was the best son anybody could have wished for. The best

child

anybody could have wished for.

I always wondered why she bothered having me if that was the case. I asked Norma about this once. It was when she still lived at home and worked in the chippie, so I must have been about nine or ten. She was getting ready to go out and I stood and watched her glue a pair of false lashes to her eyelids and smear some Max Factor, Coral Glow across her lips.

‘You were a mistake, Violet,’ she said as she backcombed her hair. ‘You were conceived out of despair and grief.’ One thing you can say about Norma – she doesn’t mince her words.

I don’t like to think of Mum and Dad ‘doing it’ because of

grief

and

despair

(I don’t like to think of them doing it at all!). It must have been a very snotty affair. I know what Mum’s like when she cries. It makes me feel sick to think of it, it’s so disgusting.

I bet when Mum found out she was pregnant at her time of life, she thought a miracle had happened. I bet she thought that Joseph was coming back to her again. I remember though, that when Mrs Rice, the midwife, eventually scooped me up from the mess on the newspapers and plonked me into Mum’s arms, there was a long silence. That was disappointment. Even then, only minutes old, I knew that.

I think about Joseph a lot. It’s hard not to with Mum going on about him all the time. I imagine him in his plane, flying high in a clear blue French sky, the skin on his face stretched tight and white with determination. I imagine the thud and shock of light and noise as his plane is hit by German bullets. What was he thinking as his plane spiralled to the ground? What picture did he have in his head as he was blown to smithereens? How many bits of him were scattered across the French countryside? Did anyone ever find a piece of him? A leg, an arm, a foot still in its boot? And who would have known that any of those bits belonged to Joseph?

Nobody ever did find him though; he was declared ‘presumed dead’ in August 1945. I was three months old. Mum never put that particular letter in a frame. But the news turned her milk sour and I had to make do with rubber teats and formula after that.

It’s hard being the replacement for a hero. I never met my brother Joseph. But I hate him all the same.

I’ve always been able to see things that other people don’t see. For example, I’m the only one who seems to notice that Mr Harper the park keeper, whose face has lost its grip from his skull, likes to look up little girls’ skirts when they’re playing on the swings. But nobody would believe me if I told them.

I know when people are lying too. I can see it in their faces. When a fib flies from their mouths, a curtain is drawn across their eyes. It happens a lot. People lie all the time. Mostly about things they don’t even

have

to lie about. For example, Mum is always telling people she is ‘fine, thank you’ when they ask how she is. Why doesn’t she just tell the truth? Why doesn’t she just say, ‘I’m very sad, if you must know. And I think I will be for the rest of my life’?

I know how a person is feeling inside just by looking at them. For example, even when Mum is laughing at something Dad has said to her and is patting him affectionately on the shoulder, I know that inside she is hating him for giving her the life she has. But she wouldn’t thank me for pointing it out. And I know that although my sister Norma pretends to be irritated by babies and small children and says she loves her job at Fine Fare, I know that inside she is boiling with rage at having to work and is desperate to get pregnant.

My head is full of all sorts of brilliant stuff. I know that people suffering from Moebius Syndrome can’t smile or move their faces, that people with Apert Syndrome have webbed feet, and people with Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus are covered in patches of blue skin. If you were really unlucky and were born with all three conditions, you’d most probably be mistaken for an alien and would be taken away at birth to a secret government laboratory where you’d be dissected and slivers of your tissue would be stuck onto tiny glass slides and be peered at by scientists who smell of cleverness and Bunsen burners.

I know that male and female rats can have sex up to twenty times a day. I know that a human being will definitely walk on the moon one day, and that there are over a hundred different words for camel in the Arabic language.

I know all these things because I read a lot. Once a week, I go to the library on Lavender Hill and borrow six books. I would borrow more if they would let me. I read every type of book I can: science books, history books, poetry, encyclopaedias and novels. I’m quite clever for a girl; I even passed the 11 plus. Not that it made any difference. I always knew that as soon as I left school I’d end up here in the shop with Mum and Dad. It’s not like I had a choice or anything.

There’s other stuff I know too. For instance, even though I’ve never had a boyfriend, I know that falling in love and marrying doesn’t always make you happy. Look at Mum and Dad. Look at Norma and Raymond.

I told Norma once that she’d married the wrong man. Not that Raymond, her husband, is wicked or nasty or anything like that; he’s just so dull and flat. And he’s got these weird eyes that pop out of his sockets like marbles. Norma thinks it’s romantic that she met him at the funfair in Battersea Park.

‘He swept me off my feet,’ she likes to say.

But he didn’t. He worked on the Helter Skelter and all he did was hand her a mat to slide down on, and asked her out for a drink afterwards. I think she only married him so she didn’t have to work in the chippie any more. She should have waited. She could have married someone loads nicer than Raymond. He’s a taxi driver now (he’s not clever enough to be a proper cabbie. His brain’s not big enough for all that ‘Knowledge’) and there’s no fizz to him, and I know Norma is a fizzy type of girl. Or she used to be before she married Raymond. She didn’t like it when I told her this though. ‘Shut up, Violet,’ she said. ‘What do you know about anything? You’re only sixteen, for God’s sake!’

Oh, and that’s another thing. I know that

God

doesn’t exist, and people who think he does are delusional; but you have to be polite and not criticise their beliefs and every time you write the word God, you have to use a capital letter, but if you ever have to write the word fairy or goblin or ghost, you don’t.

‘Violet!’ said Mum in her most horrified voice, when I mentioned this to her one day. ‘You can’t go around saying things like that!’

From the way Mum’s lips pulled together, like she’d been sucking on a lemon sherbet, you’d have thought I’d said FUCK, which is apparently the worst word a human being can utter according to Mum. But I think there are much worse words, such as ‘get your apron on, Violet,’ fish suppers and bloody, bloody chips. I don’t know why Mum gets so worked up about things like that. It’s not like she even goes to church or anything. And I don’t believe for one second that she still thinks God exists. If he did, how could he have let her son die? How could he have let thousands of young men die? How could he have let millions of Jews be murdered? If God does exist he must be the evilest thing in creation. Worse even than Hitler.

I get really pissed off with being told what to say and what to think; as if I haven’t got a mind of my own. I’m sixteen now. I’m not a child.

There’s a new song that’s been playing on the wireless recently. I always stop what I’m doing and listen to it whenever it comes on. It’s sung by a girl called Helen Shapiro and she’s only fourteen. It’s called

Don’t Treat Me Like a Child.

I’ve memorised the lyrics. They capture exactly the way I feel. That just because I’m only in my teens doesn’t mean I should be treated like a child. I’ve got my own dreams and opinions, and I’ve got my own mind. I’m not a little girl any more.

I’m not daft enough to think the song was written just for me. But it’s nice to think there’s somebody else out there who feels the same way that I do. I know me and Helen Shapiro would be really good friends if we were ever to meet. Anyway, I always sing along really loudly whenever her song comes on, just to make my point.

‘Turn that bloody racket off, Violet!’ Dad shouts. ‘And get your apron on. There’s customers waiting.’

I wish he wouldn’t speak to me like that. One day I’ll show him. One day I’ll show them all. I’m not going to be stuck in this shop for ever, you know. I’m not going to spend the rest of my life stinking of salt and vinegar and cod and chips.

I’m not going to be invisible for ever. I’m not going to be a shrinking Violet for ever. I’m going to do something to get myself noticed. One day it will be my photograph up on the mantelpiece.