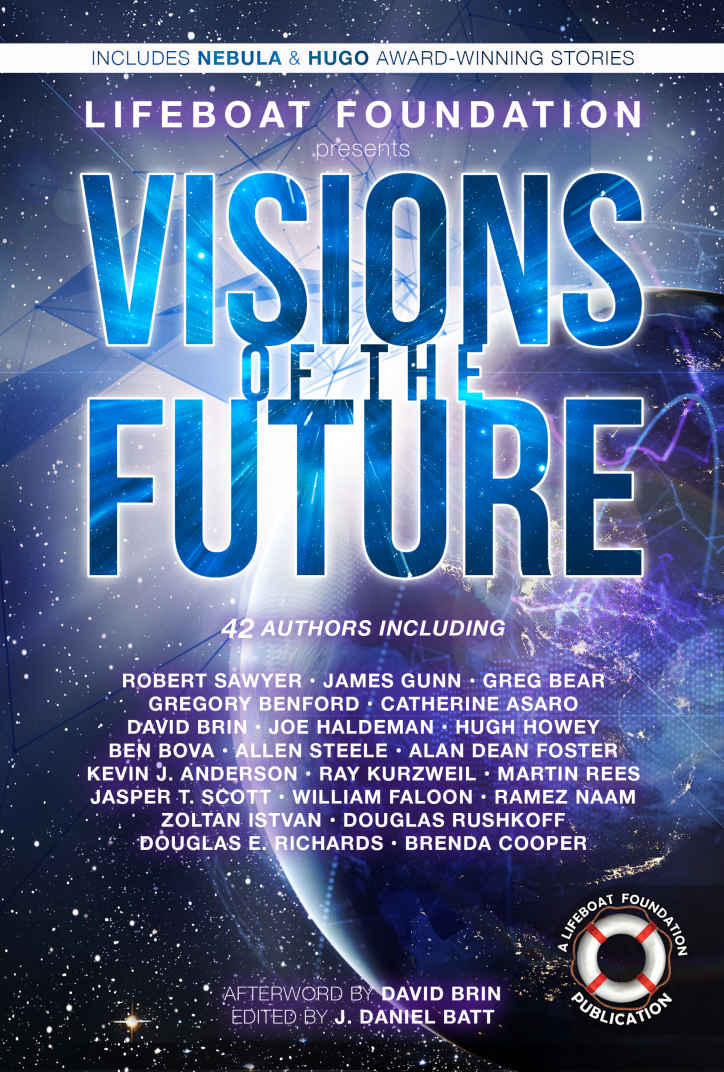

Visions of the Future

Read Visions of the Future Online

Authors: David Brin,Greg Bear,Joe Haldeman,Hugh Howey,Ben Bova,Robert Sawyer,Kevin J. Anderson,Ray Kurzweil,Martin Rees

Tags: #Science / Fiction

LIFEBOAT FOUNDATION

presents a collection of stories & essays including Nebula & Hugo award-winning works

In Visions of the Future you’ll find stories and essays about artificial intelligence, androids, faster-than-light travel, and the extension of human life. You’ll read about the future of human institutions and culture. But these literary works are more than just a reprisal of the classical elements of science fiction and futurism. At their core, each of these pieces has one consistent, repeated theme: us.

PRAISE RECEIVED BY AUTHORS

(AND US!)

“Benford may be at his best in his shorts.” —Chicago Tribune

“Bear is one of the few SF writers capable of traveling beyond the limits of mere human ambition and geological time.” —Locus

“Ray Kurzweil is the best person I know at predicting the future of artificial intelligence.” —Bill Gates

“Martin Rees is one of our key thinkers on the future of humanity.” —TED

“They don’t write ‘em like that anymore! Except Asaro does, with no false nostalgia, but rather an up-to-the-minute savvy!” —Locus

“In the last few years, Canadian science fiction has undergone an unprecedented boom. Native Canadians are turning out solid SF, and of these the foremost is undoubtedly Robert J. Sawyer.” —The Toronto Star

“Combines the feel of classic SF adventure with strong, character-driven storytelling and lays the foundation for other tales set in Cooper’s brave new world.” —Library Journal

“It’s a page turner. Istvan knows how to tell a compelling story.” —io9.com

“Lifeboat Foundation is a nonprofit that seeks to protect people from some seriously catastrophic technology-related events. It funds research that would prevent a situation where technology has run amok, sort of like a pre-Fringe Unit.” —The New York Times

Published by Lifeboat Foundation

© 2015 by Lifeboat Foundation

All rights reserved.

Authors hold their individual copyrights on the stories and essays included here as described in our acknowledgements section.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

This anthology includes works of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

ISBN-13: 978-0692513781

ISBN-10: 0692513787

Edited by J. Daniel Batt

Afterword by David Brin

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

OTHER BOOKS BY LIFEBOAT FOUNDATION

The Human Race to the Future: What Could Happen—and What to Do

by Daniel Berleant

Prospects for Human Survival

by Willard H. Wells

Learn more at

lifeboat.com/ex/books

.

Table of Contents

Introduction by J. Daniel Batt

Robert J. Sawyer • The Shoulders of Giants

Alan Dean Foster • Gift of a Useless Man

Catherine Asaro • Light and Shadow

Nicole Sallak Anderson • The Birth of the Dawn

Douglas Rushkoff • Last Day of Work

Allen Steele • The Emperor of Mars

Brenda Cooper • My Father’s Singularity

Kevin J. Anderson • A Delicate Balance

Joe Haldeman • More Than the Sum of His Parts

Gregory Benford • Lazarus Rising

Clayton R. Rawlings • Unit 514

J. Daniel Batt • The Boy Who Gave Us the Stars

Chris Hables Gray • The Etiology of Infomania

Frank W. Sudia • Looking Forward: Dialogs with Artilects in the Age of Spiritual Machines

Hugh Howey • The Automated Ones

Peg Kay • The Billionaires’ Gambit

J.M. Porup • The Children of Men

Jeremy Lichtman • Down In the Noodle Forest

Ille C. Gebeshuber • A Requiem for Future’s Past

Coni Ciongoli Koepfinger • Get the Message

Lawrence A. Baines • New Age Teacher

Lord Martin Rees • Our Final Hour

Ray Kurzweil • The Significance of Watson

Eric Klien • Proof That the End of Moore’s Law Is Not the End of the Singularity

José Cordeiro • The Future of Energy: Towards the “Energularity”

William Faloon • Intolerable Delays

Tom Kerwick • Enhanced AI: The Key to Unmanned Space Exploration

James Blodgett • Do It Yourself “Saving the World”

Zoltan Istvan • Will Brain Wave Technology Eliminate the Need for a Second Language?

Brenda Cooper • Smart Cities Go to the Dogs: How Tech-savvy Cities Will Affect the Canine Population

Heather Schlegel • Reputation Currencies

Douglas E. Richards • Scientific Advances Are Ruining Science Fiction

Michael Anissimov • 10 Futuristic Materials

INTRODUCTION

j. daniel batt

In the following pages you’ll find stories and essays about artificial intelligence, androids, faster-than-light travel, and the extension of human life. You’ll read about the future of human institutions and culture. But these literary works are more than just a reprisal of the classical elements of science fiction and futurism. At their core, each of these pieces has one consistent, repeated theme: us. You are in these pages. I am in these pages.

Exploration of the future is not just pondering what’s out there or what’s to come. It is a discussion of how we as humans will react to what we encounter. How will we respond to androids, extraterrestrial life, and humans that have seemingly unlimited lifespan? How will we react to technologies that bridge colossal gaps of distance? We have not always met new technologies and philosophies with enthusiasm. Patterns of thought and belief that are thousands of years old still hold sway in shaping our reactions. What seemed to be obvious societal advances, in hindsight, were actually challenging battles.

If we encounter intelligent life amongst the stars, what will we do? Will our response be one of mutual curiosity and sharing? Or, instead, suspicion and fear?

This book,

Visions of the Future

, is not just a handy collection of pulp sci-fi adventures and articles. It continues a necessary conversation our society is having. Our responses now will shape our responses to come. If our relationship today with what is both new, unknown, and different is derived from fear, it’s not a far extrapolation to see that mentality carried forward. Hugh Howey’s “The Automated Ones” projects current fear-based bigotry into our relationship with AI life. Nicole Anderson’s “The Birth of the Dawn” shows a different relationship to human 2.0—one built on enthusiasm and wonder. The very challenges we face today will be mirrored in the future.

Science fiction has already begun to shape the way we think. Thomas M. Disch, in

The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of

, writes, “It is my contention that some of the most remarkable features of the present historical moment have their roots in a way of thinking that we have learned from science fiction.” Science fiction and futurism can be both predictive and prescriptive. Today’s TASER is an acronym for Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle, referencing the pulp science fiction classic that gave inspiration to the modern-day inventor. Beyond technological foresight, science fiction functions as a lab for thought experiments. It allows us to imagine scenarios that are to come and then analyze them. Through the stories, we also analyze ourselves. We are reflecting back our own beliefs about humanity and our own fears.

The future isn’t predetermined. We are not guaranteed the stars. We are not guaranteed another century on this planet. We are not guaranteed this planet. Through resilience and incredible fortune, the future may turn out far more marvelous than even the stories in this book could imagine. But it will not just happen.

This is what this book in your hands is about: our relationship with our future. Will we be dragged into the future, kicking and screaming? Will we stumble into it? Will we flee back to the caves in fear of it? Or will we run to it? Create it? Design it?

This book is not a road map, but, hopefully, it can inspire the map makers. As you read these pages, keep in mind Dennis Cheatham’s words from

The Power of Science Fiction:

“It may be the case that the future worlds and infinite possibilities projected in science fiction can be used to inspire viewers to pursue work that will make those possibilities or ones like them, real.” It’s possible that one of the futures you’ll read in these pages might actually end up being right. But even the ones that will get it wrong (and let’s be honest, most science fiction does) are still critical for us now. It’s difficult to overstate the significance of the practice of science fiction on shaping us today. The most important aspect about explorations of the future is that they be written and be read.

So, enjoy reading. Find yourself in these pages. Discover our future in the words ahead.

FICTION

“Individual science fiction stories may seem as trivial as ever to the blinder critics and philosophers of today—but the core of science fiction, its essence, the concept around which it revolves, has become crucial to our salvation if we are to be saved at all.”

—Isaac Asimov

THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

robert j. sawyer

Rob is one of only eight writers in history—and the only Canadian—to win all three of the world’s top science fiction awards for best novel of the year: the Hugo, the Nebula, and the John W. Campbell Memorial Award.

Read his

Red Planet Blues

at

http://amzn.to/1B7cE52

.

It seemed like only yesterday when I’d died, but, of course, it was almost certainly centuries ago. I wish the computer would just tell me, dammitall, but it was doubtless waiting until its sensors said I was sufficiently stable and alert. The irony was that my pulse was surely racing out of concern, forestalling it speaking to me. If this was an emergency, it should inform me, and if it wasn’t, it should let me relax.

Finally, the machine did speak in its crisp, feminine voice. “Hello, Toby. Welcome back to the world of the living.”

“Where—” I’d thought I’d spoken the word, but no sound had come out. I tried again. “Where are we?”

“Exactly where we should be: decelerating toward Soror.”

I felt myself calming down. “How is Ling?”

“She’s reviving, as well.”

“The others?”

“All forty-eight cryogenics chambers are functioning properly,” said the computer. “Everybody is apparently fine.”

That was good to hear, but it wasn’t surprising. We had four extra cryochambers; if one of the occupied ones had failed, Ling and I would have been awoken earlier to transfer the person within it into a spare. “What’s the date?”

“16 June 3296.”

I’d expected an answer like that, but it still took me back a bit. Twelve hundred years had elapsed since the blood had been siphoned out of my body and oxygenated antifreeze had been pumped in to replace it. We’d spent the first of those years accelerating, and presumably the last one decelerating, and the rest—

—the rest was spent coasting at our maximum velocity, 3,000 km/s, one percent of the speed of light. My father had been from Glasgow; my mother, from Los Angeles. They had both enjoyed the quip that the difference between an American and a European was that to an American, a hundred years was a long time, and to a European, a hundred miles is a big journey.

But both would agree that twelve hundred years and 11.9 light-years were equally staggering values. And now, here we were, decelerating in toward Tau Ceti, the closest sunlike star to Earth that wasn’t part of a multiple-star system. Of course, because of that, this star had been frequently examined by Earth’s Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. But nothing had ever been detected; nary a peep.

I was feeling better minute by minute. My own blood, stored in bottles, had been returned to my body and was now coursing through my arteries, my veins, reanimating me.

We were going to make it.

Tau Ceti happened to be oriented with its north pole facing toward Sol; that meant that the technique developed late in the twentieth century to detect planetary systems based on subtle blueshifts and redshifts of a star tugged now closer, now farther away, was useless with it. Any wobble in Tau Ceti’s movements would be perpendicular, as seen from Earth, producing no Doppler effect. But eventually Earth-orbiting telescopes had been developed that were sensitive enough to detect the wobble visually, and—

It had been front-page news around the world: the first solar system seen by telescopes. Not inferred from stellar wobbles or spectral shifts, but actually seen. At least four planets could be made out orbiting Tau Ceti, and one of them—

There had been formulas for decades, first popularized in the RAND Corporation’s study

Habitable Planets for Man

. Every science-fiction writer and astrobiologist worth his or her salt had used them to determine the

life zones

—the distances from target stars at which planets with Earthlike surface temperatures might exist, a Goldilocks band, neither too hot nor too cold.

And the second of the four planets that could be seen around Tau Ceti was smack-dab in the middle of that star’s life zone. The planet was watched carefully for an entire year—one of its years, that is, a period of 193 Earth days. Two wonderful facts became apparent. First, the planet’s orbit was damn near circular—meaning it would likely have stable temperatures all the time; the gravitational influence of the fourth planet, a Jovian giant orbiting at a distance of half a billion kilometers from Tau Ceti, probably was responsible for that.

And, second, the planet varied in brightness substantially over the course of its twenty-nine-hour-and-seventeen-minute day. The reason was easy to deduce: most of one hemisphere was covered with land, which reflected back little of Tau Ceti’s yellow light, while the other hemisphere, with a much higher albedo, was likely covered by a vast ocean, no doubt, given the planet’s fortuitous orbital radius, of liquid water—an extraterrestrial Pacific.

Of course, at a distance of 11.9 light-years, it was quite possible that Tau Ceti had other planets, too small or too dark to be seen. And so referring to the Earthlike globe as Tau Ceti II would have been problematic; if an additional world or worlds were eventually found orbiting closer in, the system’s planetary numbering would end up as confusing as the scheme used to designate Saturn’s rings.

Clearly a name was called for, and Giancarlo DiMaio, the astronomer who had discovered the half-land, half-water world, gave it one: Soror, the Latin word for sister. And, indeed, Soror appeared, at least as far as could be told from Earth, to be a sister to humanity’s home world.

Soon we would know for sure just how perfect a sister it was. And speaking of sisters, well—okay, Ling Woo wasn’t my biological sister, but we’d worked together and trained together for four years before launch, and I’d come to think of her as a sister, despite the press constantly referring to us as the new Adam and Eve. Of course, we’d help to populate the new world, but not together; my wife, Helena, was one of the forty-eight others still frozen solid. Ling wasn’t involved yet with any of the other colonists, but, well, she was gorgeous and brilliant, and of the two dozen men in cryosleep, twenty-one were unattached.

Ling and I were co-captains of the

Pioneer Spirit.

Her cryocoffin was like mine, and unlike all the others: it was designed for repeated use. She and I could be revived multiple times during the voyage, to deal with emergencies. The rest of the crew, in coffins that had cost only $700,000 a piece instead of the six million each of ours was worth, could only be revived once, when our ship reached its final destination.

“You’re all set,” said the computer. “You can get up now.”

The thick glass cover over my coffin slid aside, and I used the padded handles to hoist myself out of its black porcelain frame. For most of the journey, the ship had been coasting in zero gravity, but now that it was decelerating, there was a gentle push downward. Still, it was nowhere near a full g, and I was grateful for that. It would be a day or two before I would be truly steady on my feet.

My module was shielded from the others by a partition, which I’d covered with photos of people I’d left behind: my parents, Helena’s parents, my real sister, her two sons. My clothes had waited patiently for me for twelve hundred years; I rather suspected they were now hopelessly out of style. But I got dressed—I’d been naked in the cryochamber, of course—and at last I stepped out from behind the partition, just in time to see Ling emerging from behind the wall that shielded her cryocoffin.

“’Morning,” I said, trying to sound blasé.

Ling, wearing a blue and gray jumpsuit, smiled broadly. “Good morning.”

We moved into the center of the room, and hugged, friends delighted to have shared an adventure together. Then we immediately headed out toward the bridge, half-walking, half-floating, in the reduced gravity.

“How’d you sleep?” asked Ling.

It wasn’t a frivolous question. Prior to our mission, the longest anyone had spent in cryofreeze was five years, on a voyage to Saturn; the

Pioneer Spirit

was Earth’s first starship.

“Fine,” I said. “You?”

“Okay,” replied Ling. But then she stopped moving, and briefly touched my forearm. “Did you—did you dream?”

Brain activity slowed to a virtual halt in cryofreeze, but several members of the crew of

Cronus

—the Saturn mission—had claimed to have had brief dreams, lasting perhaps two or three subjective minutes, spread over five years. Over the span that the

Pioneer Spirit

had been traveling, there would have been time for many hours of dreaming.

I shook my head. “No. What about you?”

Ling nodded. “Yes. I dreamt about the strait of Gibraltar. Ever been there?”

“No.”

“It’s Spain’s southernmost boundary, of course. You can see across the strait from Europe to northern Africa, and there were Neandertal settlements on the Spanish side.” Ling’s Ph.D. was in anthropology. “But they never made it across the strait. They could clearly see that there was more land—another continent!—only thirteen kilometers away. A strong swimmer can make it, and with any sort of raft or boat, it was eminently doable. But Neandertals never journeyed to the other side; as far as we can tell, they never even tried.”

“And you dreamt—?”

“I dreamt I was part of a Neandertal community there, a teenage girl, I guess. And I was trying to convince the others that we should go across the strait, go see the new land. But I couldn’t; they weren’t interested. There was plenty of food and shelter where we were. Finally, I headed out on my own, trying to swim it. The water was cold and the waves were high, and half the time I couldn’t get any air to breathe, but I swam and I swam, and then…”

“Yes?”

She shrugged a little. “And then I woke up.”

I smiled at her. “Well, this time we’re going to make it. We’re going to make it for sure.”

We came to the bridge door, which opened automatically to admit us, although it squeaked something fierce while doing so; its lubricants must have dried up over the last twelve centuries. The room was rectangular with a double row of angled consoles facing a large screen, which currently was off.

“Distance to Soror?” I asked into the air.

The computer’s voice replied. “1.2 million kilometers.”

I nodded. About three times the distance between Earth and its moon. “Screen on, view ahead.”

“Overrides are in place,” said the computer.

Ling smiled at me. “You’re jumping the gun, partner.”

I was embarrassed. The

Pioneer Spirit

was decelerating toward Soror; the ship’s fusion exhaust was facing in the direction of travel. The optical scanners would be burned out by the glare if their shutters were opened. “Computer, turn off the fusion motors.”

“Powering down,” said the artificial voice.

“Visual as soon as you’re able,” I said.

The gravity bled away as the ship’s engines stopped firing. Ling held on to one of the handles attached to the top of the console nearest her; I was still a little groggy from the suspended animation, and just floated freely in the room. After about two minutes, the screen came on. Tau Ceti was in the exact center, a baseball-sized yellow disk. And the four planets were clearly visible, ranging from pea-sized to as big as grape.

“Magnify on Soror,” I said.

One of the peas became a billiard ball, although Tau Ceti grew hardly at all.

“More,” said Ling.

The planet grew to softball size. It was showing as a wide crescent, perhaps a third of the disk illuminated from this angle. And—thankfully, fantastically—Soror was everything we’d dreamed it would be: a giant polished marble, with swirls of white cloud, and a vast, blue ocean, and—

Part of a continent was visible, emerging out of the darkness. And it was green, apparently covered with vegetation.

We hugged again, squeezing each other tightly. No one had been sure when we’d left Earth; Soror could have been barren. The

Pioneer Spirit

was ready regardless: in its cargo holds was everything we needed to survive even on an airless world. But we’d hoped and prayed that Soror would be, well—just like this: a true sister, another Earth, another home.

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?” said Ling.

I felt my eyes tearing. It

was

beautiful, breathtaking, stunning. The vast ocean, the cottony clouds, the verdant land, and—

“Oh, my God,” I said, softly. “Oh, my God.”

“What?” said Ling.

“Don’t you see?” I asked. “Look!”

Ling narrowed her eyes and moved closer to the screen. “What?”

“On the dark side,” I said.

She looked again. “Oh…” she said. There were faint lights sprinkled across the darkness; hard to see, but definitely there. “Could it be volcanism?” asked Ling. Maybe Soror wasn’t so perfect after all.

“Computer,” I said, “spectral analysis of the light sources on the planet’s dark side.”

“Predominantly incandescent lighting, color temperature 5600 kelvin.”

I exhaled and looked at Ling. They weren’t volcanoes. They were cities.

Soror, the world we’d spent twelve centuries traveling to, the world we’d intended to colonize, the world that had been dead silent when examined by radio telescopes, was already inhabited.

The

Pioneer Spirit

was a colonization ship; it wasn’t intended as a diplomatic vessel. When it had left Earth, it had seemed important to get at least some humans off the mother world. Two small-scale nuclear wars—Nuke I and Nuke II, as the media had dubbed them—had already been fought, one in southern Asia, the other in South America. It appeared to be only a matter of time before Nuke III, and that one might be the big one.