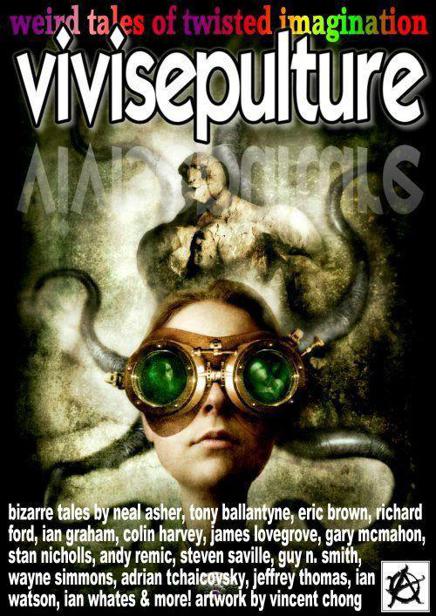

Vivisepulture

Authors: Wayne Andy; Simmons Tony; Remic Neal; Ballantyne Stan; Asher Colin; Nicholls Steven; Harvey Gary; Savile Adrian; McMahon Guy N.; Tchaikovsky Smith

Tags: #tinku

Contents

PLASTIPAKTM LIMITED by NEAL ASHER

PRETTY TEETH by TONY BALLANTYNE

BUKOWSKI ON MARS, WITH BEER by ERIC BROWN

THE EVISCERATORS by RICHARD FORD

YOU ALWAYS REMEMBER YOUR FIRST by LEE HARRIS

TORTURER’S MOON by COLIN HARVEY

CAUGHT IN THE SHADOW by VINCENT HOLLAND-KEEN

BIBLE BASHER by JAMES LOVEGROVE

WIND PROJECT NX104 by JORDAN REYNE

METAmorphosis by STEVEN SAVILE

KITTY WANTS A HITTY by WAYNE SIMMONS

ZOMBIE GUNFIGHTER by GUY N SMITH

PIPEWORK by ADRIAN TCHAIKOVSKY

THE LOST FAMILY by JEFFREY THOMAS

TALES FROM THE ZOMBIBLE by IAN WATSON

THE DEVIL IN THE DETAILS by IAN WHATES

Vivisepulture

weird tales

of

twisted imagination

in the tradition of

Poe, Kafka & Borges

edited by

Andy Remic

& Wayne Simmons

Published 2011

by

Anarchy Books

This anthology is dedicated to

Colin Harvey

A great writer taken before his time.

Colin Harvey

1960-2011

INTRODUCTION

by

ANDY REMIC

A lot of things have deviated since I first started putting together

VIVISEPULTURE.

The original concept was to ask fellow authors for stories based around the bizarre and weird, having just written my own weird little tale called

SNOT.

Having enjoyed writers like Poe, Kafka, Orwell and Borges in the past, I thought it would be an interesting experiment to find out what my fellow scribblers could come up with when charged with plumbing the depths of their own twisted, feral, and nightmare imaginations...

What transpired was this incredible collection you now hold in your hands. I can honestly say I was amazed by the quality of the stories submitted, and that I also thoroughly enjoyed reading each and every one; and indeed, was amazed by the depths of depravity many of my friends had allowed their minds to sink to in order to supply a bizarre tale for

VIVISEPULTURE.

A very sad event during the compilation of this tome was the untimely death of Colin Harvey, one of the contributors, and a fellow writer with whom I’d shared many an entertaining signing session in book shops and conventions around the UK. We laughed a lot. It was good. So, it is with great affection this anthology is dedicated to Colin.

Be warned, there are many stories within this volume which will shock; they will amaze you, as if you’re experiencing a freak at a Victorian circus; and you will in turn be stunned, and slapped, and pushed towards the outer limits of madness...

For

VIVISEPULTURE

is not a read to be taken lightly. No. You must dim the lights, envelop yourself in a calm, quite, brooding atmosphere; maybe pour yourself a stiff sherry or a single malt; prepare for transportation into bizarre Other Realms; and hope that

YOU

, Dear Reader, never succumb to the act of vivisepulture...

Andy Remic, December 2011.

PLASTIPAK

TM

LIMITED

by

NEAL ASHER

The spade went two inches into the ground and grated to a halt. Three hours to dig the holes, he had priced it at, but he had not reckoned on ground with a two-inch layer of dirt over what appeared to be compacted ballast. Even so, though the job had taken him longer than expected, he gained satisfaction from being paid to plant trees rather than cut them down. At the last hole, with the last tree to go in, he gazed across at the factory as the next shift of blue-overalled clones arrived with plastic sandwich boxes and tabloids tucked under their arms. What work satisfaction did they have?

The last tree dropped into the hole sweet as pie and Morris tipped the last of the compost in around it. The excess soil went into a nearby hollow in the uneven ground. When the job was done he tossed his tools and empty compost bags into the back of his van and wiped his hands on a cloth. Now came the enjoyable bit: handing in an invoice. Not quite as enjoyable as paying cheques into his bank account, but not far off.

Morris sat in his van and wrote out the invoice, occasionally glancing toward the sprawl of the factory, the work-shops and warehouses, fork-lifts and lorries, stacks of large cardboard boxes on pallets, and ubiquitous workers in their blue overalls. Present your invoice to the supervisor they had said. How was he to know which of them was the supervisor? He stuck a cigar in his mouth, and after turning on the ignition pressed in the cigarette lighter and returned his attention to the invoice.

Everything was listed, barring prices. His quote had been eighty: the trees costing thirty-three and the compost a tenner; that left forty-seven for five hours work. Sod it. There was all the driving about and organising things. He upped the price of the trees by ten pounds and the compost by five pounds. Ninety-five. Not into the hundreds, so hopefully acceptable.

Puffing cigar smoke he climbed out of his van and headed for the factory.

“Where’s the supervisor?” he asked a blank blue girl. She gave him a watery smile and pointed to a white-coated figure walking toward one of the units. The clipboard was a dead giveaway. Morris trotted in that direction with clods of mud flying from his hiking boots.

The supervisor walked through swing doors into an area filled with the factory racket; the hiss of air rams and the clank of unidentifiable mechanisms. What the Hell did they make here? The place was called Plastipak and by the reels of plastic being carted in he guessed the products must be something like plant pots. But no one was sure. The workers here never used the local pub and those he had run into elsewhere were a close-mouthed bunch.

“Hey! Excuse me!”

His shout was drowned by the noise. He pushed on through the doors ignoring the ‘Personnel Only’ sign. The rules did not apply to him for he was his own man. Ahead of him the supervisor turned a corner and he trotted to catch up. Round the corner he heard the familiar k-chunk of a clocking-in machine. It was a sound he had grown to hate, along with the rip and click of sandwich boxes opening. To him it epitomised all he hated about factories and was part-and-parcel of his motivation for becoming self-employed.

The supervisor was watching a row of blue-clad workers clocking in. Slaves to time, they took their cards from one rack, dipped them in the work-clock, then placed them in the next rack along. K-chunk. A piece of cardboard bitten away – eight hours of a life.

Morris paused by a machine and rested against its hot cowling. He glanced aside at the machine-operator and frowned. Pull the lever, press the button, open the shield and drop something white into a box. Close the shield, pull the lever ... mind-numbing. Soul-destroying. It was no wonder to Morris that they were always advertizing for factory hands. This place seemed to have an appetite for them.

He leant back against the cowling, puffed on his cigar, and looked up at a ‘No Smoking’ sign. Sod ‘em. He continued smoking.

The last of the blues filed past the clock and lost themselves in the oily spaces between the machines, yet the supervisor still stood there with his clipboard clasped to his chest. Morris was about to approach him when he saw another worker sauntering up. Late, obviously, and in for a bollocking Morris reckoned.

“Late again, Mitchell.”

Mitchell did not seem impressed with this observation. He ignored the supervisor as he took the remaining card from the rack and pressed it into the clock.

So I’m late. Who cares?

As the card entered the clock, stainless steel jaws rose out of it and closed. K-chunk. Mitchell screamed and staggered back holding the wrist of the hand with square-cut fingers. Blood beaded the oily concrete.

“Oh dear. You’re hurt.”

The supervisor caught hold of him under the arm and led him from the clock. Morris stared, his cigar forgotten for a moment.

“My fingers...” Mitchell managed.

“They’ll be fine,” said the supervisor, and did not relinquish his hold. Mitchell was white-faced, fainting. The supervisor half-carried him down the aisle between the loom of black engines.

Morris blinked and tried to figure out what he had seen. What exactly had happened? In a stunned fugue he dropped his cigar to the ground and walked over to the clocking-in machine. Blood on the floor, blood around the slot in the top of the machine, no sign of fingers. He had imagined it. Mitchell must have cut himself on the rack. It was the only sensible explanation. He followed the supervisor and his charge.

Mitchell’s feet were dragging and he looked completely out of it. Where was Medical in this place? Surely not right back here. Morris walked to one side of the trail of blood as the supervisor took the injured man deeper into the roar of machinery. Ahead of him, the two were silhouetted against the open mouth of a furnace when they came to a halt. The supervisor all but carried Mitchell to one side, then left him in amongst some machinery and went to operate some controls. Morris approached the supervisor from behind, ready to start with the ‘excuse mes’. The he glanced aside at Mitchell.

The man was coughing up blood. A meat hook had gone in under his right shoulder blade and come out under his sternum. The supervisor pressed a button and Mitchell was hoisted into the air poised at an angle, weakly struggling as he was carried along the conveyer line to the furnace. Morris had time to see the ‘Rejects’ sign above the furnace door before he ducked behind a vibrating hopper. Hiding there in greasy shadow he heard a ripping sound and Mitchell’s final screams.

Christ! This wasn’t happening! He had to get out, get to his van, leave the grounds of the factory and call the police. But the evidence? Would there be any identifiable remains in the furnace? Would there still be fingers in that clock? What was the purpose of those hooks? The conveyer machinery stilled and he listened carefully to the sound of the supervisor’s boots crunching on the granular plastic spilt on the floor. He peeked out of hiding and watched him walk away. Only as he came out of hiding did he notice one of the machine-operators working nearby.

“Jesus! Hey! Did you see that!?”

The worker continued to pull his levers and press his buttons. Morris ran up to him, grabbed him by the shoulder and spun him round. Raw hollows stuffed with toilet paper faced him, and the tears running from the eye-sockets were of pus. Morris released the worker’s shoulder and the man swivelled back to his machine and continued his monotonous task. Morris stepped away, suddenly cold, shuddering.

“What the Hell is going on here?”

No one answered. The machines just kept on rumbling and hissing, thumping and groaning. Conveyers conveyed and moulding machines moulded and the people in the gaps between pressed their buttons and pulled their levers.

Morris looked to where the supervisor had gone and headed in a different direction. He had to get out, and he did not want the supervisor to know he had been in.

In a new aisle he ducked a shower of sparks and leapt a jet of steam, glanced through a perspex screen and saw white granules pouring into a hopper. He hid in an alcove between steel walls covered with chipped green paint as a woman pushed a trolley past, followed her for a moment, then ducked into another aisle.

An open conveyer belt hissed and jerked slowly past him. On it rested a neat line of skulls. He picked one up and finding it to be made of plastic he laughed uneasily. Well, someone had to make those plastic skeletons for medical colleges. He dropped the skull back on the belt and, as he moved along, what hysterical amusement he felt fled him. I’m having a nightmare. I’ll wake up in a bit.