Volt: Stories

Advance Praise for

Volt

“Alan Heathcock’s voice is the American voice, doing what it was meant to do. It’s full of distance and wind, highways and heart. He’s the real deal.”

—Luis Alberto Urrea, author of

Into the Beautiful North

“The stories in

Volt

are rich in surprise moments of brightness and bleakness, told in strong straight sentences. Alan Heathcock has a cowpoke’s eye for the bloom and detritus of the landscape, and language that puts one right there in the picture, banging through the greasewood, the cornfield, crossing the flats and sudden gullies. These are tough and potent stories, deeply felt and imagined. Heathcock is a writer who goes without flinching into the darker corners of human experience, but has the grace to bring any available light with him.”

—Daniel Woodrell, author of

Winter’s Bone and Tomato Red

“Alan Heathcock is an epic storyteller—and

Volt

is an epic collection. You will come away from each of these majestic stories thrilled, alternately terrified and heartened, ultimately full of wonder at how the author manages to make twenty pages so timeless, so deep and sweeping—every story like a novel writ small.”

—Benjamin Percy, author of

The Wilding

and

Refresh, Refresh

“In the tradition of Breece D’J Pancake and Kent Meyers, Alan Heathcock turns his small town into a big canvas. Like the tales in

Winesburg, Ohio,

the stories in

Volt

are full of violence and regret, and the sad desperation of the grotesque.”

—Stewart O’Nan, author of

Songs for the Missing

VOLT

Copyright © 2011 by Alan Heathcock

“The Staying Freight” first appeared in the

Harvard Review.

“Smoke” first appeared in the

Kenyon Review.

“Furlough” first appeared in

Storyville.

“Peacekeeper” first appeared in the

Virginia Quarterly Review.

“Fort Apache” first appeared in

Zoetrope: All-Story.

This publication is made possible by funding provided in part by a grant from the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature, a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and private funders. Significant support has also been provided by Target; the McKnight Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-55597-577-7

Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-025-3

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2011

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010937515

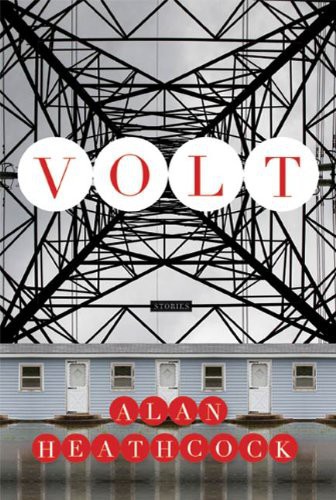

Cover design: Kyle G. Hunter

Cover photo: Vstock LLC / Getty Images

For Rochelle

VOLT

THE STAYING FREIGHT

1

Dusk burned the ridgeline and dust churned from the tiller discs set a fog over the field. He blinked, could not stop blinking. There was not a clean part on him with which to wipe his eyes. Tomorrow he’d reserved for the sowing of winter wheat and so much was yet to be done. Thirty-eight and well respected, always brought dry grain to store, as sure a thing as a farmer could be. This was Winslow Nettles.

Winslow simply didn’t see his boy running across the field. He didn’t see Rodney climb onto the back of the tractor, hands filled with meatloaf and sweet corn wrapped in foil. Didn’t see Rodney’s boot slide off the hitch.

Winslow dabbed his eyes with a filthy handkerchief. The tiller discs hopped. He whirled to see what he’d plowed, and back there lay a boy like something fallen from the sky.

Winslow leapt from the tractor, ran to his son. With his belt, he cinched a gash in the boy’s leg. He pressed his palm to Rodney’s neck. Blood purled between his fingers. Winslow cradled his son in his lap and watched the tractor roll on, tilling a fading arc of dust toward the freight rail tracks that marked the northern end of all that was his.

2

Lights flashed and bells dinged. Winslow stopped his truck at the crossing. A freight engine emerged from the woods, shuddered around the bend. Winslow eyed the train’s iron wheels, eyed the hillside beyond the tracks, his old clapboard house, round-roofed barn, grain silos perched above the barley. The train chugged nearer. It’d take twenty minutes to pass. Winslow had thirty-seven acres to swath, had lost so much time with his boy’s death, with the funeral and relatives, with long hours holding his wife, Sadie, so many tears she’d cried, so much water in one woman.

The crossing shook. The freight horn shrieked, wailing louder, nearer. Winslow stomped the accelerator. The truck lurched onto the tracks and the engine’s nose filled his window. He jerked the wheel and the pickup swerved, rocked, but stayed on the road. He sped up the hill, boxcars flashing in his rearview mirror, train brakes screeching and freight joints howling as the line clawed to a halt.

From high in his combine, Winslow eyed the dormant train, the engine far to the west, the coal cars deep into the eastern woods. An hour had passed and there it sat. Winslow’s nerves were frayed. He turned his gaze to the reels cutting under the barley. Blackbirds burst from the field. From the corner of his eye, Winslow noticed a flash of white in the crop, then a crouching man sprang and dashed in front of the harrower.

Winslow yanked the brake, struck his head against the back window. His pulse thumped in his throat as he shut down the combine.

Then someone was pounding on the cab, and there stood a man, out of breath, in a white dress shirt under soiled gray coveralls. Winslow threw open the door, hopped down into the field.

“What the hell you doing, mister?” Winslow shouted.

The man pressed nose to nose with Winslow. His eyes were flushed as if from weeping, his hair white as the moon, and a scar split his lips and curled like a pig’s tail onto his cheek.

“Could’ve killed you,” he lisped.

Winslow glanced at the combine. “I could’ve killed

you

.”

“You son of a bitch,” the man barked. “I’m giving you a taste of your own.”

“Watch your mouth, mister,” Winslow said. “You don’t know me from Adam.”

The man took Winslow by his overall straps and slung him to the ground. He stood over Winslow, noon sun glinting off sweat in the curl of his scar. “Ain’t gonna do it no more,” the train man said, pointing down in Winslow’s face. “So you just go to hell.”

The wind blew the man’s hair up into white flames. Winslow set his jaw, thought the man would strike him. Instead, the freight man stood tall, raised the zipper of his coveralls, and took off running.

Winslow watched him sprint up the slope, away from the tracks, away from his train. He ran high-kneed through the barley, past Winslow’s house, past the barn and silos, never stopping, never looking back. Soon he was a speck on the horizon, and, as if slipping through a pinhole in the sky, the freight man was over the ridge and gone.

3

For a long time, Winslow sat in the barley, determined to finish his work. But then, his hands shaking, eyes pulsing, he was overcome by a fever. It’d taken all his will just to return to the house.

Now Winslow gathered himself in the foyer. He slumped against a wall, listening to the squeak of a chair. In the front parlor, a woodpaneled room that was dark despite bay windows, Sadie worked needlepoint, yarn draping the sofa, purples and reds and golds unfurled about her rocking chair.

“Taking a break,” Winslow called, and hurried back to the kitchen. His eyes burned. His temples throbbed. He pulled open the freezer door and out tumbled frozen peas. Winslow slid down the fridge to the tile floor. He held the peas to his face.

“Hungry, Win?” Sadie asked from the hall, her footsteps approaching, and then she was in the kitchen.

“Win?”

Winslow closed his eyes, could feel her at his side, her hot hand on his neck, the other on his forehead.

“Oh, Win,” she said. “You’re burning up.”

Sadie was a furnace blasted over him. Her fingers seared his cheeks, his throat. He pleaded,

“Leave me be,”

then

“Please, hon,”

but she wouldn’t move, and the heat rose up in him, his shoulders quaking, his arms.

Winslow thrust his hands against Sadie. She tripped, fell hard against the kitchen table, tumbled to the floor. She lay under the table, clutching her skull.

Winslow rushed to her. “Hon,” he said, afraid to touch her. “I’m so sorry, hon.”

Sadie turned a cheek against the tile, pulled her hand from her hair. Blood streaked her palm.

Winslow lay awake, aware of his muscles, of his heavy breathing, the groan of the bedsprings. The doctor had given Sadie painkillers and she slept soundly beside him. A swath of her hair had been shaved, her stitches stained orange from the iodine.

Now and forever I’ll be the man what killed his boy. A man what shoved his wife. Winslow wanted to wake Sadie and apologize again and again. He was so riled. He rolled gently out of bed and fumbled in the darkness with his overalls and boots.

Winslow bumped down the hall to a door they now kept locked. As a drunk warns himself from a tavern, he’d warned himself from this room. He set his forehead against the door, trying to remember Rodney’s face. But only the freight man came to mind, that white hair, the man running, receding through the barley.

Sweat beaded upon Winslow’s brow. He hurried into the bathroom and splashed cold water over his face. Again he recalled the freight man shrinking on the ridge, vanishing.

Winslow stepped to the doorway. Moonlight from the parlor trailed up the stairs. He crossed the hall, peered down into the glow. Sadie had removed all the photos of Rodney from the stairwell, and as Winslow descended he traced his fingertips over the nails on which they’d hung.

The front parlor was washed in moonlight. Winslow stepped to the bay window. The land outside was bright. He let his eyes drift far down the slope of barley. At the field’s base crouched the wall of train, a lampblack silhouette, a driverless freight.

Why hadn’t they come for it? Wouldn’t someone miss it by now? Blood ticked in Winslow’s skull. The train man’s scarred cheek bristled in his mind. That man just ran away. He just left.

Winslow hurried to the kitchen and rummaged through drawers for a notepad and pen. He didn’t know what to write. He scribbled:

Took a walk. Be back soon.

Winslow read it once, considered its meaning. He had no plan. Just to walk. To settle himself a bit. Winslow folded the paper. He held it to his lips then left it on the kitchen table.