WAR CRIMES AND ATROCITIES (True Crime) (9 page)

Read WAR CRIMES AND ATROCITIES (True Crime) Online

Authors: Janice Anderson,Anne Williams,Vivian Head

Right up to the present day the country has been hampered by civil wars, and even now there is no stable government to improve the state of the Congo. It would be fair to say that much of the instability of the present country can be traced back to the atrocities of Leopold II.

Balangiga Massacre

1901

The Balangiga Massacre, which took place in a small seaside village on the island of Samar in the Philippines, personified the brutality of the Philippine– American War. The 9th Infantry Regiment of the US Army sailed into Balangiga on 11 August, 1901. The batallion consisted of 74 veterans, led by Captain Thomas Connell and was in response to the mayor’s request for protection from rebel forces. When they arrived in the town, the US soldiers took over the affairs of the town and forcibly took occupation of some the local’s huts. Although relations between the soldiers and the villagers were friendly when they first arrived, things started to deteriorate rapidly. The soldiers issued an order that all male residents from the age of 18 were to clean up the town in preparation for an official visit by their superior officers. While these men were busy, the soldiers allegedly abused one of their women, which led to retaliation by the villagers. On top of this, Captain Connell ordered the destruction of all food stores in the town for fear of it falling into the hands of the Filipino guerilla forces.

VILLAGERS FIGHT BACK

The already angry people of Balangiga, feared that they would starve in the coming rainy season without their food stores, and decided to attack the US garrison. At 6.45 a.m. on 28 September, 1901, the villagers made their move. Having killed the few armed sentries, the chief of police, Valeriano Abanador, ordered his people to attack. The US soldiers, who were having breakfast at the time, were taken completely by surprise as men rushed into their camp armed with axes and

bolos

(Filipino knives), many of them disguised as women. Most of the soldiers were simply hacked to death, while Captain Connell managed to lead a few of his men out onto the street, but they didn’t survive for long. The soldiers fought back as best they could, using anything they could get their hands on, including knives from the kitchen and chair legs. One private even used a baseball bat to fight off his attackers.

A few of the soldiers who managed to escape feared for their lives and fled the island by boat to a nearby garrison. Out of the original 78 men of the 9th Infantry Regiment, 54 were killed or missing, 20 were severely wounded and only four managed to escape unhurt.

US

RETALIATION

What became known as the ‘Balangiga Massacre’ was the subsequent brutal retaliation on the inhabitants of Samar Island by the occupying US forces. The morning after the attack, two US batallions landed on Balangiga, along with two of the survivors of the attack. When they arrived they found Balangiga had been abandoned, so they buried their dead and razed the village to the ground.

The leader of the batallions, General Jacob H. Smith ordered Major Littleton Waller, commanding officer of the Marines, to tell his men to clean up the island of Samar, saying, ‘I want no prisoners. I want you to kill and burn; the more you kill and burn the better it will please me.’ He ordered that any Filipinos who did not surrender and were able to bear arms, should be shot, and this included anyone over the age of ten.

What ensued was a bloody massacre of the Filipino residents on Samar Island, leading to the death of thousands of Filipino. Smith’s strategy was simple, cruel, but effective. By blocking all trade with Samar, he planned to starve the revolutionaries into submission. He said that all Filipinos were to be treated as enemies unless they could prove otherwise, for example, by giving the soldiers information as to where the guerillas were hiding or if they agreed to work as spies. Other than that anyone who appeared to be a threat should be shot on sight. Large columns of US soldiers marched their way across the island, destroying homes, shooting people and killing their animals.

The only thing that stopped a full-scale annihilation of Samar was that many of Smith’s subordinates did not agree with his policy, which meant that many of the civilians escaped with their lives. When news of the abuses reached the USA at the end of March 1902, there was public outrage. Added to the atrocities committed by the US army, they stole three national treasures before they left Samar. One was a rare 1557 cannon and the other two were Balingiga church bells. Almost 100 years after the massacre, the current Philippine government is still trying to have these trophies of war returned to their shores.

COURT MARTIAL

The US Secretary of War ordered an investigation into the atrocities in the Philippines and brought court martial proceedings against General Smith and Major Waller. Waller was tried first, and the court martial began on 17 March, 1902. He was tried for the execution of 11 native guides, who had reportedly found edible roots during a long march, but had failed to share this knowledge with the starving US troops. Waller said that he was simply ‘obeying orders’ and was acquitted, a defence which the US army did not allow when trying enemies in Nuremberg decades later.

In May 1902, General Smith was tried, not for war crimes, but on the charge of ‘conduct to prejudice of good order and military discipline’ and that he had given orders to Waller to take no prisoners. The court martial found Smith guilty and sentenced him to be ‘reprimanded by a reviewing authority’.

In an effort to try and appease the subsequent public outcry, President Roosevelt ordered Smith’s retirement from the army. He received no further punishment

for the atrocities that had taken place in the Philippines. It will always remain a matter of contention whether the killing of thousands of Filipinos was really justification for the murder of 54 US soldiers, and whether these killings amounted to war crimes or crimes against humanity.

The Sinking Of The Lusitania

1915

When the German army marched into neutral Belgium on 4 August, 1914, they displayed a blatant disregard for international treaties and made it easier for Britain to become involved in World War I. Unlike World War II, World War I is not really associated with atrocities carried out by military forces against either civilians or enemy soldiers. However, this story proves that World War I was not fought with totally clean hands, as reports that came out of northern France and Belgium proved. During the months of August and September 1914, German troops are reported to have carried out wholesale murder of civilians without any obvious provocation. Stories of mass executions, rapes, mutilations and arson were widespread, and both the French and British governments set up special enquiries into the alleged German ‘atrocities’ in Belgium. The report outlined horrific sexual and sadistic crimes, although there was a strong reaction to its content claiming that much of the information had been grossly exaggerated. Whatever the truth behind these atrocities, it does illustrate the ambivalent moral boundaries that are crossed during the time of war. What was regarded by one side as an ‘atrocity’ was simply seen by the other as a ‘necessity’ to win the war.

The incident of the sinking of the liner

Lusitania

on 7 May, 1915, had a major influence on the involvement of the United States in World War I, and it still stands out in history as a singular act of German brutality.

THE

FATEFUL

VOYAGE

The

Lusitania

was a British cargo and passenger ship that made its maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in September 1907. She was a giant of a ship, built to speed through the water at an average of 25 knots. Powered by a 68,000 horse power engine, she had been dubbed the ‘Greyhound of the Seas’, and it wasn’t long before she won the prestigious Blue Ribbon Award for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic.

The

Lusitania

had been built to Admiralty specifications, with the understanding that it would be turned over for government service at the onset of war. As the rumours of war started to spread in 1913, the

Lusitania

was secretly taken into the dry docks at Liverpool and was fitted out to be ready for service. This included the fitting of ammunition magazines and gun mounts, which were concealed under her polished teak deck, ready for when they were required.

The

Lusitania

had crossed the Atlantic many times over the years without any problems, but as World War I intensified and German submarines took a threatening role in the seas, her situation became far more precarious. Due to her speed, the

Lusitania

was considered to be unsinkable, believing that she would simply be able to flee if she came under attack. Because of this confidence in her construction and power, the

Lusitania

was allowed to set sail from New York on

1 May, 1915, with the sole purpose of delivering goods and passengers to England.

When she left for Liverpool, England, the

Lusitania

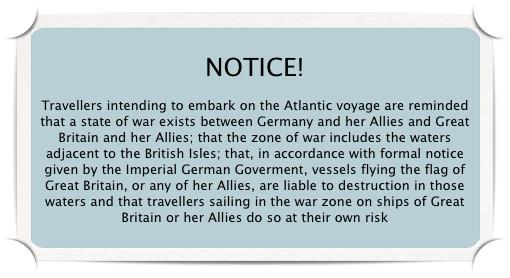

carried a large number of US passengers, despite the fact that the German authorities had published a warning in US newspapers on the morning of her departure. The notice read:

Many of the 1,257 passsengers believed that the luxury liner was unlikely to be a target to the Germans as it had no military value. However, unknown to her passengers, apart from her normal cargo of meat, medical supplies, copper, cheese, oil and machinery, the

Lusitania

also carrying a large quantity of munitions for the British to use during the war.

The

Lusitania

was captained by William Turner who, with his experience and a crew of 702, should certainly have been on alert for any Germany activity. As the giant liner left the shores of New York, a German U-boat was leaving, captained by Captain Walter Schwieger. He had been ordered to sail to the northern tip of Great Britain, join the Irish Channel and destroy any ships travelling from and to Liverpool, England. Schwieger was known to have frequently attacked ships without giving any warning, firing at any he suspected of being British.

Before the

Lusitania

set out on its voyage, it was decided to only light 19 of the 25 boilers on board to save on the enormous consumption of coal. This meant that the

Lusitania

was now limited to a speed of 21 knots, still much faster than a U-boat submarine, with a top speed of 13 knots.

The first few days of the luxury liner’s voyage were uneventful, unlike those of the German submarine. As Schwieger rounded the south-west tip of Ireland, he attempted to destroy several ships, but was unsuccessful. The same day he spotted a small schooner, the

Earl of Lathom

, and first surfacing to warn crew, opened fire and destroyed the boat. The following day Schwieger continued his journey to the Irish Sea, firing torpedoes at the steamer

Candidate,

and about two hours later he destroyed another ship, the

Centurion

. For some reason, even though the captain of the

Lusitania

received several warnings that a German U-boat had destroyed three British ships in the waters he was about to cross, he failed to take any action to avoid being attacked.

Schwieger was running low on fuel by this point and instead of travelling past Liverpool, he decided to turn back. This meant that the

Lusitania

and the U-boat were about to cross paths.

THE

FATAL

ENCOUNTER

On 7 May, the

Lusitania

entered the most dangerous part of her journey and, apparently concerned about poor weather conditions, Captain Turner actually slowed the boat down. On top of that, Turner was ignoring all the rules for avoiding attack, sailing too close to the shore, where the U-boats usually sat in waiting. However, Turner trusted his own instincts and experience and ordered extra lookouts and ordered that the lifeboats be swung out ready for evacuation.

Shortly before the U-boat and the

Lusitania

met, Schwieger had spotted an old war cruiser, the

Juno

. However, he was unable to hit his target because the captain was using the zigzagging tactic, which made it difficult to fire at due to its constantly changing course. Captain Turner, however, did not use this tactic because he felt that it wasted both time and fuel.

At 1.20 p.m. the U-boat spotted something large in its sight:

Starboard ahead four funnels and two masts of a steamer with a course at right angles to us . . .

Schwieger submerged and stealthily approached the enormous steamer. At 1.40 p.m. the

Lusitania

was about 700 m (765 yd) away and even turned towards the U-boat, making its target much easier. Schwieger ordered for a single torpedo to be fired.

On board the

Lusitania

, the passengers had just finished their lunch. As Captain Turner went down to his cabin, an 18-year-old lookout by the name of Leslie Morton spotted a burst of bubbles about 400 m (440 yd) from the liner. Then he saw another line of bubbles travelling at about 22 knots, heading towards the starboard (right) side of the ship. Aware that this meant trouble, Morton quickly grabbed the megaphone and shouted to the bridge:

Torpedoes coming on the starboard side.

Just a few seconds later, the lookout posted in the crow’s nest, Thomas Quinn, sounded the alarm when he noticed the torpendo’s wake. Captain Turner quickly ran to the ship’s bridge, but as he reached it the torpedo exploded on impact.

There was a large explosion as the torpedo penetrated the hull just below the waterline. The initial explosion set off a violent secondary blast, which appeared to come from the bottom of the ship. The

Lusitania

tilted to the right at an angle of 25 degrees. The wireless room had to tap out its SOS message using battery power, as the main power had gone out with the explosion.

Because of the violent tilt of the ship, the lifeboats on the port (left) side were unable to be launched. The lifeboats on the starboard side were swung out so far, that it meant passengers had to make a huge leap from the deck to actually get into the boats. Many of the crew members panicked as the ship started to sink, launching lifeboats that only carried a few people. Some of the lifeboats capsized, and some were damaged when the torpedo hit, so, despite the fact that the

Lusitania

carried enough lifeboats for everyone on board, the simple fact was that the majority of them could not be launched for one reason or another.

Within 18 minutes of the torpedo hitting the ship, the

Lusitania

sank, taking with it 1,195 of the 1,959 on board. Captain Turner jumped as the water covered the bridge, and he swam around for about three hours before being rescued by a nearby lifeboat, which was already overloaded with people.

Captain Walter Schwieger had watched through his periscope from the moment the torpedo hit the

Lusitania

, and made notes in his log. It clearly stated that his U-boat only fired one single torpedo, but that it caused an unusually large explosion. The secondary explosion was due to the 4,200 cases of small arms ammunition that the

Lusitania

was carrying in its hold, making her a legitimate target for the German U-boat.

The distress signals sent out by the

Lusitania

reached Queenstown, Ireland, which was about 17 km (10 miles) away. Vice Admiral Sir Charles Coke organized as many rescue ships as he had available and told their captains to sail to where the Lusitania had sent its last signal. It took them about two hours to reach the six remaining lifeboats and any survivors still in the water. In total they picked up 761 people, a disaster that had only been rivalled by the sinking of the

Titanic

in 1912.

THE

FULL

IMPACT

News of the disaster was sent across the Atlantic to New York, and partly because of the large number of Americans on board, they were outraged at the sinking of the Lusitania. Out of the 197 who boarded the liner only 69 survived. Riots occurred in many countries at the injustice of the attack, and stores worldwide refused to serve any German customers. Anti-German protests and political cartoons started to appear with regularity, and President Woodrow Wilson sent the first of four notes regarding the

Lusitania

incident on 13 May.