War of the Eagles

WAR

of the

EAGLES

Eric Walters

O

RCA

B

OOK

P

UBLISHERS

Copyright © 1998 Eric Walters

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in review.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Walters, Eric, 1957-

War of the eagles

ISBN 1-55143-099-1 (pbk.)

1. Haida Indians â Juvenile fiction. I. Title.

PS8595.A598W37 1998Â Â Â Â Â Â Â jC813'.54Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C97-911119-6

PZ7.W1713Wa 1998

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97-81084

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support of our publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Department of Canadian Heritage, The Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Ministry Arts Council.

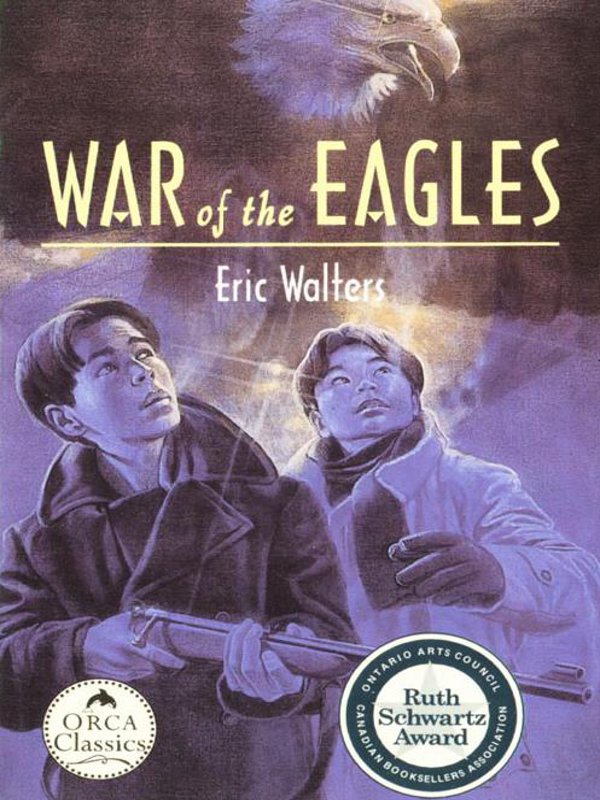

Cover painting and design by Ken Campbell

Printed and bound in Canada

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 5626, Station B

Victoria, BC Canada

V8R 6S4

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 468

Custer, WA USA

98240-0468

02  01  00  â¢Â  6  5  4

Dedication

When I was ten years old, I was searching through our old cedar chest and came across a picture of my father, much, much younger, wearing an army uniform and holding an eagle in his outstretched arms. The eagle was dead. I didn't understand how this could be. My father was a tough man, someone who didn't always have a lot of time for people, but he always had time for animals. We never had much money, but if a stray and injured cat wandered by, what money we had would go towards fixing whatever was wrong.

It was unimaginable to me that my father could have killed that eagle. I asked him to tell me what had happened. Reluctantly, he told me a small sliver of a story. Over a period of time, a few more episodes escaped. As it turned out, he was telling me about the most exciting time in his life â the time he spent as a soldier stationed in Prince Rupert during the Second World War.

Almost thirty years later, those fragments inspired this novel. On the day I finished the final draft of War of the Eagles my father passed on. He never got the chance to see the finished novel or to read this dedication.

My father taught me a lot in life. Perhaps the most impor

â

tant lesson he taught was the importance of cherishing the events which surround you and of realizing that the “good old days” are happening right now. This novel is for you, Dad.

Dedicated to my father, Eric George Walters. December 7, 1915 â August 28, 1997.

Contents

I felt the weak yellow light from the morning sun, although its face still remained hidden behind the mountain tops. A thick layer of fog clung waist high to the ground, but gathered into deeper pools in the nooks and depressions of the forest floor. The chill in the air felt good as each breath filled my lungs; cool, moist air, scented with the aroma of the trees. The tops of the tallâest trees, Douglas firs, red cedars, hemlock and Sitkas, disappeared into the gloom, lost from my view. Below, the small cedars and other evergreens fought amongst themselves to capture whatever sunlight managed to filter through the giants above.

The ground was littered with deadfall and my steps were announced by the cracking and snapping of twigs. Hardly audible, but to the creatures of the forest the sound was a loud cry of warning. Every few steps I would stop . . . and listen. Listen. Listen. Moving through the underbrush, my clothes became increasingly damp from the dew clinging to the leaves and needles. Small ferns, moss and fungus were everywhere.

The ground became soft and silent. I was standing on a section of muskeg, one of many extending throughâout the forest in places where the water never leaves the ground. This was good. The spongy earth muffled my clumsy footfalls and, for now, I was as noiseless as any other animal. Between the softness under my feet and the white fog floating all around, I imagined I was walking on a cloud.

Both my father and grandfather had been my guides and teachers during earlier morning outings. All their differences were gone when they were out together hunting. We always went out at dawn because that's the best time. The creatures of the night, tired from hunting or being hunted, are less careful before they seek out their refuge from the day. The creatures of the day, not yet completely in their time, are unsure of themselves. Alone on this morning I didn't fear the forest or the animals that lived, and died, within it.

I couldn't help but think of my grandfather. Cradled in my arms was his gun, an old Enfield .303. The wooden handle was worn, the barrel darkened with age, but the sights were true and it shot straight. Straight and true. Like my grandfather. Even when he was old and stooped, he still stood straight and true.

He always said his rifle had a magic spirit which helped guide its bullets to the target. My father didn't believe in such things. He said my grandfather was just “one heck of a shot.” I know my father was right, but still, each time I squeezed the trigger I hoped there was magic.

My father was gone too. Gone off to fight a war halfway around the world. He'd be coming back someâday, but that didn't make it any easier when I missed him. We'd spent so much time together. Hunting and fishing, flying together in his bush plane, just talking. He'd laugh at me if I ever told him just how much he and my grandfather, my mother's father, were alike. The proud and stubborn Haida, and the proud and stubborn Englishman.

My mother's and grandmother's people were Tsimâshians. Both the Tsimshians and Haida believe in many things.

When a Tsimshian dies, if he's led a good life, he comes back to earth as an eagle or a raven or another one of the creatures of the forest or ocean. My father tells me not to believe everything I'm told, not to get caught up in all that “Indian mumbo jumbo.” My mother just smiles and says those stories make as much sense as the ones the ministers tell us in church.

Looking up, I caught my first sight of the morning sun peeking through the towering evergreens. The fog and dew were being drawn back up into the sky.

Off to the left I caught a glimpse of movement. I froze in my steps and slowly, ever so slowly, pivoted toâward the motion. There, flitting in and out of the bushes and the remaining threads of mist, was a jackrabbit. Fat and satisfied from a night of feeding, it was too content to notice me. In slow motion, I drew the rifle up. The handle felt smooth against my cheek, my finger rested against the trigger. I took aim.

The hare, nibbling on a few more blades of grass, was squarely in my sights. It stopped eating and looked up, right at me. Gentle, soft eyes, so alive, so innocent. I squeezed the trigger and with a deafening noise the bullet flew and ripped through the hare's chest, driving it violently backwards. I lowered the rifle, shouldered it and walked over to pick up the carcass. It had been blown back under a bush. I crouched down and reâtrieved it, dragging it out by its back legs.

It was long and limp, its soft brown eyes open and vacant. Blood dripped out of the gaping hole where the bullet escaped, making the brown fur sticky and warm. It was a clean kill and I was grateful. The rabbit was dead before it even heard the shot. I opened my canvas sack â my game bag â and put the rabbit in and closed the flap.

Looking around I realized I wasn't completely sure where I was, although that wasn't a problem. The sun was bright and I'd use it as my guide to find the ocean. From there I'd just move north up the coast until I reached our village. It couldn't be much more than a mile.

The trees were now alive with the sounds of birds. My footsteps echoed back at me. I didn't have to move quietly anymore since I'd got my catch for the day. My grandfather always said “Only take what you can use, what you need.” His words were so vivid that sometimes, when I closed my eyes, it felt like I could still hear him.

My thoughts were interrupted by a new sound. At first it was so faint it could be taken for the wind blowâing through the trees. But as I moved on, it became unmistakable â the ocean. The rhythm of the waves crashed against the shore. The smell of the salt water, always present everywhere on the island, became even more pronounced. I knew it was just through this next bunch of trees, or the next, or the next. Pushing through a clump of cedars I found myself on a thin stretch of stony beach. Only a few yards away the waves were breaking and retreating. I looked around and imâmediately knew where I was. My grandmother's house was no more than a half mile up the coast, just around the next point.

Down the coast in the other direction I made out the faint outline of another village, Sikima. It had about one hundred families. All Japanese fishermen. My best friend, Tadashi Fukushima, lived there with his family: his parents, two sisters and grandmother. He and I spent a lot of time in each other's homes. It seemed like half the time he ate at my house and the other half, I ate at his.

Since before I could remember we'd always spent all our summers up here with my mother's parents, and Tadashi and I had been friends. Our friendship was one of the few things that made it even a little okay when my mother decided not to return to Victoria after the summer ended. She said, with Dad away in Europe, there really wasn't any point in leaving. This really was my mother's home. She was born and raised here. So was my Naani, and her mother and her mother and her mother. Naani says her people have been here since time began. I once kidded her that that must make this the Garden of Eden. She just smiled and said yes. I didn't care about any of that. I just wanted to go back to my school and my friends and sleep in my bed in my house. There was a big difference between visiting some place and having to live there.

The beach was covered with small, flat rocks just perfect for skipping. If my stomach hadn't been callâing me for breakfast I'd have pitched a few. Rounding the point I could clearly see home. It sat amongst two dozen other houses. They were in no particular patâtern, just haphazardly placed on little chunks of land skirting the rocky outcrops that are everywhere on the island. The houses were different sizes and shapes but each was bleached white and needed to be painted. Scattered about as they were, they looked like grains of salt dropped from a giant shaker.

Not that I ever would, but I could walk into any of the houses in our village and sit down at the kitchen table. Without a word someone would set another place at the table. Every single person in the whole village is related to me in one way or another. I have trouble figâuring it all out, but my grandmother can tell me who is my cousin or great-uncle or whatever. We're all family, all part of the same clan.

On the front porch I saw my grandmother, my Naani. She sat on the steps, a bowl held between her legs, cutting up beans. She nodded at me and a faint smile crept onto her face.

“Any magic, this morning?”

“You tell me there's magic everywhere,” I answered, “so why should this morning be any different?”

“I'm glad to hear you listen to my stories.”

“I listen to everything my Naani says. That doesn't mean I believe, but I listen.”

My grandmother can't read or write. That doesn't stop her from being a storyteller and the keeper of our clan's history. She knows about everything and everyâbody. People come to listen for hours when she talks. She's almost as good as the radio. Of course, people wouldn't know anything about the radio, since there isn't one in the entire village.

Naani is also a medicine woman. She knows about the herbs and plants growing in the forest. People who aren't feeling well come to see her and she gives them advice and medicines. They treat her the same way people in the towns treat the doctor.

I removed the sack from around my neck and dropped it on her lap. “Here's a little meat for the pot.”

She picked up the bag and looked inside. “Very litâtle. Game is all going farther into the forest. All those soldiers driving âem away.”

The game had been a lot more scarce since the solâdiers started building their camp.

Before the war everybody always stayed pretty much in Prince Rupert. Now the soldiers had built a road in, cut down trees, dragged in supplies and started putting up buildings. There were lots of soldiers. I heard when it was finished there'd be a whole battalion stationed there. Hard to imagine.