War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (11 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

‘Tanks could only have captured the citadel by means of a surprise attack, as had been attempted in 1939. The requisite conditions for such an attack did not exist in 1941.’

(3)

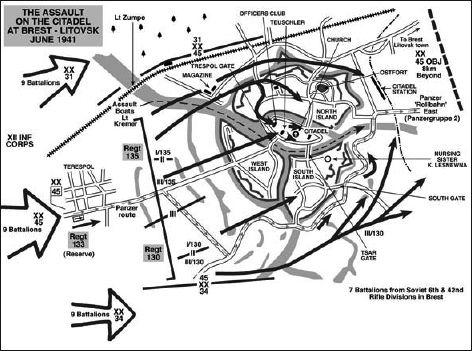

The fortress of Brest had been built in 1842. It consisted of four partly natural and partly artificial islands situated at the confluence of the Bug and Muchaviec rivers. In the centre was the Citadel Island, surrounded concentrically by three others: the western Terespol Island (referred to subsequently in the text as West Island), the northern Kobrin Island (North Island) and the Cholmsker Island to the south (South Island). The central ‘keep’ or citadel was ringed by a massive two-storey wall, easily defensible with 500 casemate and cellar positions, which doubled as troop accommodation. These positions were also connected by underground passages. Inside the walls were numerous other buildings including the ‘white house’ officers’ mess and the garrison church. The thick outer walls provided good protection against modern artillery. The West, North and South islands provided an outer defence belt, which supplemented the citadel, with 10m high earthwalls. These were studded with bastions or old casement forts complete with towers, such as the

Nordfort

(North Fort) and

Ostfort

(East Fort) on the North Island. In all, some 6km of defence works ringed the fortress.

The objective, however, possessed an Achilles’ heel. It had been built originally for all-round defence. Following the 1939 Polish campaign, the fortress network was split by the demarcation line separating the German and Soviet zones of occupation. The most relevant section, the forward defences facing west, were already in German hands. Moreover, only three gates allowed access to the 6km defensive ring in keeping with the original defence concept, adding to the reaction time required to man the fortress in the event of an alert. Maj-Gen Sandalov, the Soviet Fourth Army Chief of Staff, calculated this might take three hours, during which time the defenders would be vulnerable to considerable casualties. Only 2km of the ring faced westwards, now the main direction of threat, with room for only one infantry battalion and a half battalion of border troops. It is likely that on the night of 21 June there were about seven battalions from the 6th and 42nd Soviet Rifle Divisions in Brest in addition to regimental training units, special units and some divisional artillery regiments.

(4)

The fortress at Brest-Litovsk was built across four islands at the confluence of the Muchaviec and Bug rivers. Its all-round defence design was adversely affected by the haphazard establishment of the Russo-German demarcation line in 1939. Nine German infantry battalions conducted the break-in assault across the islands either side of the citadel and a further 18 advanced on their flanks. The northern prong with Regiment 135 attacked through West Island, and a battalion was soon cut off in the citadel while a further assault broke into North Island. Regiment 130 attacked Southern Island and bypassed the fortress further south of the River Muchaviec. Nine assault boats entered the river to the west to capture the five bridging points in successive

coup de main

operations. It was a microcosm of the coming experience on the eastern front. An operation anticipated to last one day did not cease until German forces had formed the Smolensk pocket, nearly half way to Moscow, almost six weeks later.

They would be directly faced by nine German infantry battalions with a further 18 operating on their flanks. XIIth Infantry Corps, under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Kluge’s Fourth Army, had been tasked to surround the fortress and clear a path for the vanguards of Panzergruppe 2. The inner flanks of the two Panzer corps forming it (XXIVth and XLVIth) were to be protected as they passed either side of the fortress. XIIth Infantry Corps intended to attack with three infantry divisions forward: 45th Infantry Division against Brest-Litovsk in the centre, with 31st Division left (north) and 34th Division right (south).

The 45th Division had three regiments (130th, 133rd and 135th) of three infantry battalions each. Its primary tasks were to capture the citadel, the four-span railway bridge over the Bug, five other bridges crossing the Muchaviec south of the town of Brest and secure the high ground 7–8km east of the town. This would open up the Panzer

Rollbahn

(main route) identified for Panzergruppe 2 to march eastwards towards Kobrin.

The division attack plan was based on two primary attack axes: north and south. The northern prong of a pitch-fork thrust was to attack across the West Island to the citadel, then through the North Island to the eastern side of the town of Brest. Two battalions from Regiment 135, supported by two armoured train platoons, were earmarked for this task. Meanwhile, the southern prong would assault south of the River Muchaviec across the South Island with Regiment 130. The five Muchaviec bridges were to be taken by an assault-pioneer

coup de main

force mounted within nine assault boats. One battalion was held as divisional reserve and the three battalions of Regiment 133 were to be held back as corps reserve. Nine light and three heavy batteries of the division’s artillery, supported by a group of nine heavy mortars and two 60cm siege guns would provide a pulverising five-minute preparatory surprise bombardment, before switching to nominated targets. The two flanking infantry divisions, the 34th and 31st, would also contribute to the initial barrage. A specialised, and until now secret, unit Nebel Regiment 4 (ZbV Nr 4) was to support the attack with newly developed Nebelwerfer multiple-barrelled rocket launchers. ‘Hardly a mouse would survive the opening bombardment,’ was the assurance given to the assault groups.

(5)

There was no lack of confidence. Leutnant Michael Wechtler with the reserve regiment assessed that the operation would probably be ‘easy’, noting that the first day’s objective was set 5km east of Brest. Having viewed the fortifications from a distance, the corporate view was that it appeared ‘more like normal barracks accommodation than a fortress’.

(6)

This optimism is reflected in the fact that only two of nine battalions, or 22% of the infantry force, would be in direct contact with the enemy to deliver the first blow. Three others would, meanwhile, be deploying while four waited in reserve.

The 45th Infantry Division was a veteran formation of the French campaign, where it had lost 462 dead. Like many other infantry divisions massing on the frontier, the soldiers were optimistic and well rested. While billeted in Warsaw prior to the campaign, soldiers were given the opportunity to sightsee. Many took snapshots from open horse-drawn tourist carriages. Training had been pleasant. Crossing water obstacles had been the theme. Expertise in negotiating high riverbanks in assault formation and attacking old fortifications was practised. Conditions had been idyllic. Bathing trunks were worn during off-duty moments. Watermanship often deteriorated into high-spirited splashing and clowning with races between rubber dinghies. Inventive one-man rafts were pelted with rocks, soaking the grinning occupants. There was only mild conjecture over the purpose of the training.

As they left Warsaw for the 180km approach march to the assembly area, the band of Regiment 133 played. An initial downpour of rain soaked everyone, but spirits rose again when it was replaced by a continuation of the heat wave. The march was demanding but carefully managed in 40km stages, with bathing opportunities in the lakes en route. It ended 27km from the border, where the regiments were billeted in cosy village quarters. The last of the captured French champagne was consumed with gusto and final letters written home.

Scheinwerfer

(searchlight) units were formed by squads of men who had elected to shave their heads prior to the coming campaign (they were nicknamed ‘shiny-heads’). Final ‘squad’ photographs were snapped inside the heavily camouflaged wood bivouacs. Few of these groups, it was realised, would ever muster complete again. Then in the early hours of 22 June the soldiers moved up to their final assault positions.

(7)

Shortly before 03.00 hours, Chaplain Rudolf Gschöpf stepped out of the small house in which he had been waiting. ‘The minutes,’ he remembered, ‘stretched out interminably the nearer the time to H-hour approached.’ Dawn was beginning to emerge. Only the routine noises of a peaceful night were apparent. Looking down to the river he saw:

‘There was not the slightest evidence of the presence of the assault groups and companies directly on the Bug. They were well camouflaged. One could well imagine the taut nerves that were reigning among men, who, in a few minutes, would be face to face with an unknown enemy!’

(8)

Gerd Habedanck was abruptly awoken by the metallic whir of an alarm clock inside his vehicle. ‘The great day has begun,’ he wrote in his diary. A silvery light was already permeating the eastern sky as he made his way to the battalion headquarters bunker down by the river. It was crowded inside:

‘A profusion of shoving, steel helmets, rifles, the constant shrill sound of telephones, and the quiet voice of the Oberstleutnant drowning everything else out. “Gentlemen, it is 03.14 hours, still one minute to go.”’

Habedanck glanced through the bunker vision slit again. Nothing to see yet. The battalion commander’s comment, voiced yesterday on the opening bombardment, still preyed on his mind.

‘It will be like nothing you have experienced before.’

(9)

The pilot of the Heinkel He111 bomber kept the control column pulled backwards as the aircraft continued climbing. He glanced at the altimeter: it wavered, held, then continued to move clockwise past 4,500–5,000m. The crew were signalled to don oxygen masks. At 03.00 hours the aircraft droned across the Soviet frontier at maximum height. Below was a sparsely inhabited region of marsh and forest. Even had the rising throb been discernible from the ground, nobody would have linked it to an impending start of hostilities.

Kampfgeschwader (KG) 53 had taken-off in darkness south of Warsaw, steadily climbing to maximum height before setting course to airfields between Bialystok and Minsk in Belorussia. Dornier Do17-Zs from KG2 were penetrating Soviet airspace to the north toward Grodno and Vilnius. KG3, having taken-off from Demblin, was still climbing between Brest-Litovsk and Kobrin. The aircrew scanning the darkened landscape below for navigational clues were hand-picked men, with many hours’ night-flying experience. These 20–30 aircraft formed the vanguard of the air strike. The mission was to fly undetected into Russia and strike fighter bases behind the central front. Three bombers were allocated to each assigned airfield.

(1)

They droned on towards their targets. Below, the earth was shrouded in a mist-streaked darkness. Pin-pricks of light indicated inhabited areas. Ahead, and barely discernible, was a pale strip of light emerging above the eastern horizon. There was little cloud. Only 15 minutes remained before H-hour.

Behind them, in German-occupied Poland, scores of airstrips were bustling with purposeful activity. Bombs were still being loaded and pilots briefed. Aircraft engines burst into life, startling birds who flew off screeching into the top branches of trees surrounding isolated and heavily camouflaged landing strips.

Leutnant Heinz Knoke, a Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf109 fighter pilot based at Suwalki air force station near the Russian frontier, watched as groups of Junkers Ju87 Stuka dive-bombers and fighter planes from his own unit slowly took shape in the emerging twilight. There had been rumours of an attack on Russia. ‘That appeals to me,’ he confided to his diary that night. ‘Bolshevism is the archenemy of Europe and of western civilisation.’ Orders came through earlier that evening directing that the scheduled Berlin-Moscow airliner was to be shot down. This created quite a stir. His commanding officer took-off with the headquarters flight to execute the mission, ‘but they failed to intercept the Douglas’.

Knoke had spent the earlier part of the night sitting in the mess discussing the likely course of events with other pilots. ‘The order for shooting down the Russian Douglas airliner,’ he wrote, ‘has convinced me that there is to be a war against Bolshevism.’ They sat around waiting for the alert.

(2)

‘Hardly anybody could sleep,’ recalled Arnold Döring, a navigator with KG53, the ‘Legion Condor’, ‘because this was to be our first raid.’ Aircrews had been up since 01.30 hours, briefing and preparing for a raid on Bielsk-Pilici airport. The aerodrome was thought to be full of Soviet fighter aircraft. As they hurried ‘like madmen’ about the airfield, attending to last-minute preparations, they were aware of ‘a glare of fire and a faint strip of light that signalled the approaching day’. Although these aircraft were not part of the vanguard force, already airborne, they still faced the difficulty of taking-off and forming up in the dark. ‘So many things went through my mind,’ Döring recalled. ‘Would we be able to take-off in darkness, with fully laden machines, from this little airfield, where we’d only been a few days?’