War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (37 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

As a rapid Russian collapse did not materialise, Adolf Hitler and his army planners were obliged to reconsider uneasily the future focus as the width and depth of the Russian land mass unfolded before them. One German Army photographer wrote in the Ukraine, ‘we have no more maps and can only follow the compass needle to the east’.

(1)

There were no road signs and few landmarks enabling Germans to calculate their bearings across the limitless steppes of the eastern Ukraine. Patrols and despatch riders simply asked the women and old men in the fields for directions. Poor planning and a degree of unit directional floundering resulted in these vast uncharted territories.

General Halder admitted on 11 August that ‘the whole situation makes it increasingly plain that we have underestimated the Russian colossus’. The enemy’s military and material potential had been grossly miscalculated. ‘At the outset of the war, we reckoned with about 200 enemy divisions. Now we have already counted 360’. These divisions may be qualitatively inferior to the German and poorly led, ‘but there they are, and if we smash a dozen of them, the Russians simply put up another dozen’.

(2)

As a consequence, German staffs had enormous difficulty reconciling their victories against tangible achievements. The Russians were obstinate. They would paradoxically fight bitterly to the death in one instance and surrender en masse at the next. The cumulative impact of such victories thus far, at considerable cost, seemed merely to be the attainment of ‘false crests’. Although the summit might be tantal-isingly ahead, planning fatigue tended to obscure the best means of achieving the most direct route to the objective: that of total victory.

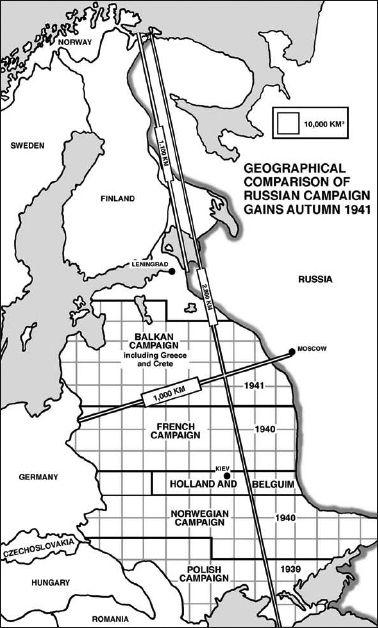

A diagrammatic representation of the vast area covered by the eastern campaign compared to previous shorter operations in the West and Balkans. Poland was conquered in 28 days, the Balkans in 24. The campaign in the West ended at the six-week point. Army Group Centre was lamenting its losses and commenting upon the difficulty of holding Russian forces inside the Smolensk pocket six weeks into the Russian campaign. Resistance at the very first pocket six weeks into the Russian campaign. Resistance at the very first pocket to be established, at Brest-Litovsk, ended only one week before.

Hitler’s controversial change of direction introduced at this stage of the campaign is often discussed with the benefit of a strategic hindsight not available to those executing decisions. It is these contemporary perceptions influencing such deliberations that ought to be considered. One school of thought opined that the Wehrmacht, stretched to its physical limit advancing into an ever-widening land mass, should concentrate its resources against one objective at a time. Generalfeldmarschall von Bock and his Panzer-gruppen and army commanders Kluge, Guderian and Hoth gave united support, to von Brauchitsch, the Wehrmacht and his Chief of Staff Halder in making Moscow the primary target. Hitler, almost perversely it seemed, elected to concentrate operations against Leningrad to the north and the Ukraine in the south. Moscow would fall as a consequence of this pressure directed against the flanks. Political and economic reasons were cited for this diversification of effort. Führer Directive Number 33, issued initially on 19 July, outlined the concept of future operations. Army Group Centre was to be divested of its two Panzergruppen – 3 (Hoth) and 2 (Guderian) – which were to be diverted from Moscow to co-operate with von Leeb and von Rundstedt in advances north to Leningrad and south to Kiev. Vacillation and confusion followed during a subsequent ‘Nineteen-day Interregnum’ (4–24 August) as commanders debated or fought their preferred operational concept at conferences. Führer Directive 34A followed on 7 August when OKW and OKH, after conferring with Jodl and Halder, persuaded Hitler of the need to resume the advance on Moscow. This was, however, rescinded three days later when renewed resistance at Leningrad frightened Hitler into insisting Hoth’s Panzergruppe 3 move north to assist von Leeb. Hitler resolved to strike southward toward Kiev. He was not deflected by a spirited presentation from Guderian, recalled from the front to brief at Rastenburg on 23 August, arguing the Moscow option for von Brauchitsch and Halder. Recriminations among the top commanders exacerbated the already vitriolic debate. Hitler, backed by Feldmarschall Keitel, Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff, and Schmundt, his chief Adjutant, patronisingly stated, ‘my generals know nothing about the economic aspects of war.’ Political, military and economic reasons were given for deflecting the advance southward into the Ukraine. Soviet air force bases in the Crimea could menace the Romanian Ploesti oilfields, economically vital to the German war effort. They had therefore to be neutralised.

Following three weeks of inertia the

Ostheer

(army of the east) was to resume the attack with a full-blooded offensive to the south. Urgency was provided by the need to conclude the Kiev operation in sufficient time to redirect an assault on Moscow before winter. The Russians, who anticipated an assault on Moscow, were astonished to see instead an attack suddenly directed to the south.

The controversy over the importance of Moscow was bound up in the army staff debate of what to do, now that the Soviet regime was prepared to fight on despite catastrophic reverses. What were the preconditions for victory in this new and not previously considered scenario? Options to circumvent the impasse might be to capture cities to create a political impact or capture ground for economic acquisition. The economic option was not seen as a rapid war-winning strategy. Gaining popular support, a measure that proved particularly effective in 1917–18, was not seriously considered due to its ideological unacceptability to the Führer. In any case it would take too long. Annihilating the Red Army remained an unfulfilled aspiration. None of the proposed strategies appeared to be working. Leningrad, ‘the cradle of Bolshevism’, was an attractive objective to Hitler, a ‘party’ man, who appreciated the ideological fibre the Communist Party conferred on the regime. Communism resided in the cities and built-up areas, not necessarily in the countryside. Panzer Leutnant F. W. Christians remembered, as his unit crossed the Ukrainian border in the middle of summer, ‘we were greeted with real enthusiasm’. It was an emotive appeal never exploited. ‘They did not just bring salt and bread,’ the traditionally hospitable Ukrainian form of greeting, ‘but also fruit and eggs,’ he declared. ‘We were warmly greeted as liberators.’

(3)

Such a psychological undercurrent was irrelevant in the Blitzkrieg context, because it had no immediate significance for military operations. The ideological end-state was, in any case, to enslave these people for the economic benefit of the Reich. A more positive outcome from a change in the direction of attack would be to strike an unexpected blow with potentially damaging consequences for the Soviet southern salient bulging westwards. A Cannae was envisaged.

Hitler’s decision caused real anguish to the High Command at OKH. Halder complained:

‘I regard the situation created by the Führer’s interference unendurable for OKH. No other but the Führer himself is to blame for the zig-zag course caused by his successive orders, nor can the present OKH, which now is in its fourth victorious campaign, tarnish its good name with these latest orders.’

(4)

But in a number of respects the Army High Command was the victim of its own confidence. There was a gulf opening up between aspiration and reality commensurate with the physical gap developing between the headquarters at the front and rear. Senior staff officers had only a limited perception of the rigours and deprivations endured by officers and men on the new Russian front. Bickering over dwindling reserves of reinforcements and logistic assets to replenish faltering Panzer advances continued; OKW and OKH were becoming complacently spoiled by a seemingly automatic flow of victories. Complaints from spearhead commanders, who repeatedly produced triumphs despite dwindling resources, not surprisingly tended to be shrugged off. Somehow, whatever the declared limitations, the German soldier managed.

Junior officers and soldiers at the front commented on the change in the direction of advance, but theirs was an uncomplicated view. They were concerned less with strategy, rather the imperative to survive or live more comfortably in a harsh environment. German soldiers were used to sudden and unexpected changes in direction. These were generally accepted without much comment because the Führer and ‘higher-ups’ invariably ‘had it in hand’. Rapid changes in the direction of the

Schwer-punkt

(main point of effort) or in risk-taking had saved the day on many an occasion in France and Crete, for example. The German soldier was conditioned to instant and absolute obedience.

Major Bernd Freytag von Lorringhoven recalled Guderian’s return from the fateful conference at Rastenburg on 23 August, after the General had failed to secure the Führer’s compliance for a continuation of the drive on Moscow. ‘We were all very astonished,’ he said, ‘…when Hitler had convinced him it was more important to push southwards into the Ukraine.’

(5)

Hauptmann Alexander Stahlberg was similarly perplexed to learn the 12th Panzer Division was to be redirected against Leningrad.

‘The order to discontinue our advance towards Moscow and go over to a defensive position had been a shock. What strategy was intended? The word had gone round at once that it had come from the highest level, that is from Hitler himself.’

Within a few days, he explained, ‘the riddle was solved’, so far as the 12th Panzer Division was concerned. ‘Moscow was no longer the priority, Leningrad was to be taken first.’

(6)

Major von Lorringhoven remarked after the war that the decision ‘is difficult to comprehend under conditions that would be prevalent today’. One simply did not question orders. He added thoughtfully:

‘One must try to imagine the fixed hierarchy that existed, a strong conception of the importance of the chain of command. It was very difficult to pose alternatives outside this convention.’

To question the change of direction was incomprehensible;‘for practical purposes that was simply not possible,’

(7)

said von Lorring-hoven.

Some soldiers have since remarked on the change, in postwar publications. Artilleryman Werner Adamczyk was informed his unit was to be diverted towards Leningrad.

‘I had a chance to look at a map of Russia. It showed the distance between Smolensk and Leningrad to be about 600km. On the other hand, the distance from where we were to Moscow was less than 400km. And we were really making progress – prisoners from the Smolensk encirclement were still passing by every day. Definitely the Russians confronting us on our way to Moscow had been beaten. And now, it seemed we were to turn away from our greatest chance to get to Moscow and bring the war to an end. My instinct told me that something was very wrong. I never understood this change in plans.’

(8)

Leutnant Heinrich Haape, with Infantry Regiment 18 on the Central Front, made similar calculations.

‘We had marched 1,000km from East Prussia, 1,000km in a little over five weeks. Three-quarters of the journey covered; a quarter still to do. We could do it in a fortnight at the most.’

There was then a pause in the normally incessant stream of marching orders. Until ‘on 30 July we received the incredible order to prepare defensive positions’.

(9)

Many postwar personal accounts point to this abrupt dispersal of effort ‘to the four winds’ with hindsight as sealing the eventual outcome of the campaign. The ‘nineteen-day interregnum’ between 4 and 24 August, which one eminent historian claims ‘may well have spared Stalin defeat in 1941’, is not a theme in contemporary diary accounts and letters home.

(10)

Ordinary soldiers may comment on plans after the event, but during conflict it rarely occurs to them. Soldiers did what they were told. Most of their letters reflect a desire to get the campaign finished. If this warranted a change in the direction of attack, then so be it. Survival and conditions at the front are what they wrote about.

Optimism was tempered with an increasing frustration at the way the campaign was being drawn out. ‘If this tempo is maintained,’ wrote a Düsseldorf housewife to the front, ‘then Russia’s collapse will not be long in coming.’

(11)

An Obergefreiter declared on 8 August that ‘since this morning the battle is now raging for the cradle of the Bolshevist revolution. We are now on the march to Leningrad.’ Despite bitter resistance from ‘committed communists’, and facing rain and storms, the advance ‘could not be held up by them’.

(12)

Another infantry Gefreiter with Army Group South wrote on 24 August, ‘the enemy fought bitterly at several positions but, nevertheless, had to fall back with heavy losses’. Many of his comrades ‘were left dead or wounded on the battlefield. This war is dreadful,’ he lamented.

(13)

There was more frustration at the requirement in the centre to go over to the defensive and engage in static positional warfare than comment about the opening thrust to the south. ‘I’m already fed up to the eye-teeth with the much vaunted Soviet Union,’ declared an Unteroffizier from the 251st Infantry Division.