War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 (59 page)

Read War Without Garlands: Operation Barbarossa 1941-1942 Online

Authors: Robert Kershaw

‘We hard-hearted soldiers have no time to bemoan his fate. We tie down our helmets and think of revenge, revenge for our dead comrades. The battle of Vyazma is over and the last elite troops of the Bolsheviks have been destroyed.’

(22)

The Soviet pockets at Bryansk, however, held on. On 14 October two battalions from the ‘Grossdeutschland’ Infantry Regiment were ordered to conduct a night attack on Annino, to prevent further seepage by Soviet forces from the beleaguered pocket. Nobody relished the prospect of a night attack. Both battalion commanders were depressed, knowing casualties would be heavy. Company commanders registered disquiet in their own indirect way through repeated radio requests for confirmation that the attack was to go ahead. ‘No man can adequately describe the feeling that prevails before a major attack,’ admitted one eyewitness. ‘The troops sat there [during the briefings] with their notes and inner battles.’ Leadership was applied and feelings of insecurity suppressed. Oberleutnant Karl Hänert, a veteran Knight’s Cross holder, wounded three times, represented the steadying influence that kept soldiers moving despite nervous stress. He was 27 years old and his orders were ‘cold and clear’.

‘The possibility of a failure on one of the attack’s wings was thrashed out mathematically and without feeling. He issued his orders no differently than on a peacetime exercise. Everyone knew what he had to do. Beyond that, everyone knew as well what he could do.’

After the attack went in, reports came back one after the other of company commanders killed or wounded. Hänert was shot in the head by a Soviet sniper. Another company commander, in post barely four weeks before, also died. The news of Hänert’s death was passed on by a weeping aide. ‘No one spoke a word,’ said the witness. ‘We didn’t look at each other. Everyone had been floored by the news.’ Shock enveloped them. ‘I am not sure what happened in the next hour,’ he said. The carnage continued. Several other officers were killed the same night. ‘It was difficult to comprehend that they were gone,’ reflected the witness. ‘Surely at any minute they must come up and say something to us!’ Annino was successfully taken, but during the following night another officer was killed and a second seriously wounded. They were mistakenly shot by their own sentries.

(23)

The drain on the veteran leadership of the

Ostheer

was constant and unremitting.

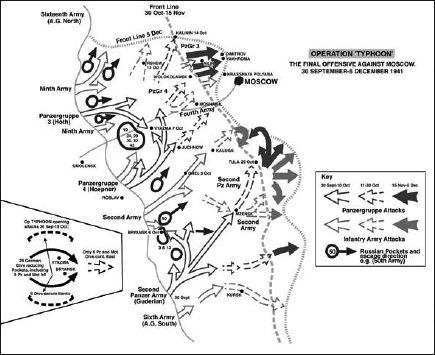

Operation

‘Taifun

’ was launched by Army Group Centre with 14 of the 19 Panzer divisions in theatre, and eight of 14 motorised infantry divisions. These ‘fast’ divisions were supported by a force of 48 infantry foot divisions marching up in depth. Twenty-five infantry divisions were reducing the Vyazma and Bryansk pockets while a further seven continued the advance to the east. Nine infantry divisions were deployed securing the flanks. Nine of the ‘fast’ divisions (six Panzer and three motorised) were intensively committed to pocket fighting, leaving six (four Panzer and two motorised infantry) continuing towards Moscow, moving west to east. A further three divisions (two Panzer and one motorised) sought to disengage from the Bryansk battles and advance on Tula and Moscow beyond on a north-easterly axis. The success of this strategy was dependent upon the destruction of the six to eight last-remaining Soviet field armies now in their grasp, standing before Moscow. Generalfeldmarschall von Bock announced in an Order of the Day on 19 October that:

‘The battle at Vyazma and Bryansk has resulted in the collapse of the Russian front, which was fortified in depth. Eight Russian armies with 73 rifle and cavalry divisions, 13 tank divisions and brigades and strong artillery were destroyed in the difficult struggle against a numerically far superior foe.’

Booty was calculated at 673,098 prisoners, 1,277 tanks, 4,378 artillery pieces, 1,009 anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns, 87 aircraft and huge amounts of war matériel.

(24)

To be successful, the strategy now required a Russian capitulation. This was anticipated. Von Brauchitsch had confided to von Bock during the heady days of the initial

‘Taifun

’ success ‘that this time it was different from Minsk and Smolensk, this time we could risk pursuing immediately’. Panzergruppe 3 was the only sizeable element of Army Group Centre still pushing eastward towards Moscow. Bock declared, still remembering his frustration at the decision prematurely to form pockets at the outset of ‘Barbarossa’:

‘I am of the view that it was just as possible at Minsk and Smolensk and that we could have saved blood and time if they hadn’t stayed the army group’s hand back then. I am not in total agreement with the drive to the north by Panzergruppe 3. Perhaps it will be spared me, for the heavy blow inflicted today may result in the enemy, contrary to previous practice, yielding opposite my front as well; some signs point to that.’

(25)

The double encirclement battles at Vyazma and Bryansk rivalled the achievement at Kiev. It represented perhaps the final and decisive Cannae. Tank commander Feldwebel Karl Fuchs was euphoric:

‘The last elite troops of the Bolsheviks have been destroyed. I will never forget my impression of this destruction. From now on, their opposition will not be comparable to previous encounters. All we have to do now is roll on, for the opposition will be minor.’

(26)

This view was clearly reflected in letters sent home across the front. An Unteroffizier with the 6th Infantry Division, jubilantly describing taking thousands of prisoners, said that ‘some are even coming voluntarily – a sign of the approaching resolution of the issue… And we are already being bombarded by press reports stating: “[Soviet] Annihilation is just around the corner!”’ Another artillery NCO with Army Group South predicted that, by the time his wife read his letter, ‘bells throughout Germany will be proclaiming victory over the mightiest enemy civilisation has ever faced’. He was totally confident. ‘It cannot last longer,’ he predicted; in fact, ‘we are puzzled what will become of us here now – are we coming back to Germany or will we stay on as occupation troops?’

(26)

It was anticipated, as in the case of the battle fought by Napoleon at Borodino, before Moscow in 1812, that the Russians might surrender their capital city, following the destruction of their field armies. If they chose not to, it would be difficult for the

Ostheer

to impose an armistice because only a fraction of its striking force was still moving eastward. Some 70% of the infantry divisions belonging to Army Group Centre were mopping up the pockets and securing its rear and flanks. Only seven divisions appeared to be still advancing. The ‘fast’ divisions had been bloodied yet again and only 40% of these were still pushing toward Moscow. Moreover, they had entered the battle at only two-thirds of their established strengths. Von Bock wished to exploit his victory. ‘If the weather holds,’ he wrote on 7 October, ‘we may be able to make up for much of what was lost through Kiev.’ He constantly chivvied his subordinates to keep the momentum going. A week later, the battle at Vyazma had been fought to a successful conclusion and the pocket at Bryansk was soon to be extinguished, but the intense fighting and awful road conditions meant Guderian’s north-east advance faltered. ‘A success for the Russians’ resistance,’ Bock concurred, ‘whose stubbornness paid off.’

(28)

An event occurred at the beginning of the second week of October which was to be recorded in virtually every letter or diary account maintained by German soldiers serving on the ‘Ostfront’. Unteroffizier Ludwig Kolodzinski, serving with an assault gun battery in the Orel area with Second Panzer Army, remembered it well. He was shaken from a deep sleep at 02.00 hours on 8 October by his radio operator, Brand. ‘Hey, Ludwig,’ Brand whispered urgently, ‘open your eyes a moment and come outside with me!’ Kolodzinski quickly pulled on a jacket and was abruptly jerked to his senses by an icy flurry of wind and something whipping into his face as he looked out.

‘It was snowing! The wind drove thick clouds of snow-flakes across the earth and the ground was already covered in a thin sheet of snow. Even the assault guns parked outside on the road had taken on a curious appearance. They were completely white as if covered in icing sugar!

‘I recorded this first snowfall in my diary and went back inside to lie down again. When I awoke in the morning and glanced outside, the snow had already gone. But as a consequence the road was covered in mud and the land around totally soaked.’

(29)

Major Johann Adolf Graf von Kielmansegg was driving forward with the 6th Panzer Division. ‘On 8 October the battle of Vyazma concluded,’ he said in a postwar interview. ‘The aim and objective of this battle had been to kick in the gates of Moscow.’ But conditions changed. ‘On 9 October, as we started to move in the north, centre and south towards Moscow, the temperature dropped and the rain began.’

(30)

The onset of poor weather affected the infantry also. ‘Yesterday we had the first snow,’ wrote an NCO with the 6th Infantry Division on the same day.

‘Not unexpectedly it was primarily rain, which had the additional disadvantage of soaking the roads. The muck is awful. Luckily the issue can’t last much longer. Our main hope at the moment is that we are not kept behind in Russia as occupation troops.’

(31)

‘The roads, so far as there were any in the western sense of the word, disappeared in mud,’ remarked Major Graf von Kielmansegg. ‘Knee-deep mud, in which even the most capable overland tracked vehicles stuck fast.’ The Russians, faced with the same problems, avoided the German tendency, through inexperience, to drive through the same ruts. Ordered to bypass Moscow to the north, 6th Panzer Division remained stuck fast in the mire for two days once the rain began. ‘The division was strung out along 300km,’ von Kielmansegg remarked, ‘whereas the normal length of a division column then was 40km.’ One soldier summed up the development thus:

‘Russia, you bearer of bad tidings, we still know nothing about you. We have started to slog and march in this mire and still have not fathomed you out. Meanwhile you are absorbing us into your tough and sticky interior.’

(32)

The colossal victory at Kiev at the end of September rekindled German public interest in the eastern campaign previously thought deadlocked. It resurrected thoughts that the war may be over before the winter. Two Russian cities had consistently held the public’s attention. Leningrad, the birthplace of the Bolshevik ideology, was anticipated to fall soon. Letters from the front stimulated rumours that the other, Moscow, had already been targeted by German

Fallschirmjäger

units, which had dropped east of the capital. Moscow was the lofty prize that would signify the war’s end. Kiev had already been compared to the World War 1 victory at Tannenberg, and public expectation was raised even further by the news of the latest Army Group Centre offensive.

The final German victories at Vyazma and Bryansk utilising favourable autumn conditions appeared to herald a final Blitzkrieg that would overcome Moscow itself. The final Russian field armies facing Army Group Centre before Moscow were surrounded and annihilated at Bryansk and Vyazma. It was a success comparable with Kiev. The German press claimed final victory even as the much weakened Panzer pincers were brought to a standstill by autumn rains and mud, and an ominously undiminished bitter resistance. The weather denied the tactical mobility thereby gained. In reality, however, the

Ostheer

was itself mortally wounded and in the throes of ‘victoring itself to death’.

‘German Autumn Storm Breaks over the Bolsheviks’, announced the

Völkische Beobachter

newspaper on 2 October. This was followed by the Führer’s announcement that ‘the enemy is already broken and will never rise again’. Rumours began to circulate that a new pocket battle for Moscow had started and that its fall was imminent.

(1)

Front letters appeared to confirm the press line. Infantryman Johann Alois Meyer, writing to his wife Klara, said, ‘you will have heard the Führer’s speech yesterday’ announcing the opening of the final offensive. ‘It ought to finish here before the onset of winter,’ he assessed. ‘That means the end of this month should see the conclusion.’ Meyer, however, hedged his bets like everyone else when he ended: ‘give thanks to God that it does come and pray to God above all else that we come through it sound in mind and limb.’

(2)