Wardragon

Authors: Paul Collins

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Fantasy & Magic

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

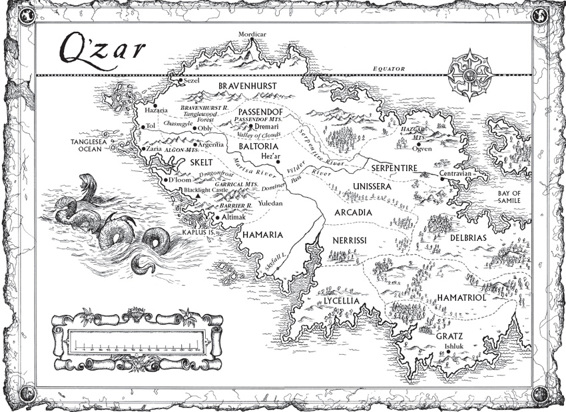

- Map

- Introduction

- 1. The Mailshirt’s New Host

- 2. The Knife’s Edge

- 3. Paraworld Killers

- 4. The Stranger

- 5. The Lure of Argentia

- 6. Mage-types and Charlatans

- 7. Golgora

- 8. History of the Green-bloods

- 9. Fa’red’s Pact

- 10. The Ragtag Army

- 11. Drip/click – Sluicing Blood

- 12. Fa’red Keeps His Word

- 13. Damaged Goods

- 14. Zimak Opens His Heart

- 15. The Belly of the Beast

- 16. The Hanging

- 17. Zimak’s Old Haunts

- 18. An Assassin’s Dart

- 19. The Funeral Pyre

- 20. The Balance

- 21. The Unravelling

- Epilogue

Wardragon

Paul Collins is a full-time writer of books for younger readers. He has been short-listed for several awards and has won the inaugural Peter McNamara, Aurealis and William Atheling awards.

Since the age of eighteen Paul has tried his hand at various occupations. He served time in the commandos, trained with the Los Angeles Hell Drivers and worked in hotel security, various factories, and for a couple of years was a film repairer for Twentieth Century Fox and MGM in New Zealand. He has played cricket, soccer, rugby union and tennis for various clubs and has a black belt in both tae kwon do and jujitsu. His kickboxing ‘career’ was short-lived although he did win his first fight with a 28-second TKO. He now weight-trains three times a week in a gym.

Paul currently lives in a rambling bluestone house in inner-city Melbourne. He shares it with children’s writer Meredith Costain and a menagerie comprising a kelpie, a red heeler, a cat, two ducks, six chickens and fifteen goldfish. Visit him at www.paulcollins.com.au and www.quentaris.com.

Also by Paul Collins

The Wizard’s Torment

Cyberskin

The Dog King

The Great Ferret Race

Sneila

The Jelindel Chronicles

Dragonlinks

Dragonfang

Dragonsight

The Quentaris Chronicles

Swords of Quentaris

Slaves of Quentaris

Dragonlords of Quentaris

Princess of Shadows

The Forgotten Prince

Vampires of Quentaris

The Spell of Undoing

The Earthborn Wars

The Earthborn

The Skyborn

The Hiveborn

The World of Grrym

Allira’s Gift

(with Danny Willis)

Lords of Quibbitt

(with Danny Willis)

BOOK FOUR IN THE JELINDEL CHRONICLES

Paul Collins

First published by Ford Street Publishing, an imprint of

Hybrid Publishers, PO Box 52, Ormond VIC 3204

Melbourne Victoria Australia

©2008

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to

Ford Street Publishing Pty Ltd, 2 Ford Street,

Clifton Hill VIC 3068.

www.fordstreetpublishing.com

First published 2008

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Author: Collins, Paul, 1954-

Title: Wardragon / Paul Collins.

eISBN: 9781925000238

ISBN: 9781876462581 (pbk.)

Series: Collins, Paul, 1954- Jelindel chronicles; bk. 4.

Target Audience: For ages 12 and over.

Subjects: Quests (Expeditions)--Juvenile fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.3

Cover design by Grant Gittus Graphics

Cover © Cathy Larsen

Map © Marc McBride

Text © Paul Collins. Visit www.paulcollins.com.au

In-house editor: Saralinda Turner

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

To Tatiana Frances, editor in the making

With thanks for the support of the May Gibbs Children’s Literature Trust which granted my fellowship at the Canberra studio in September 2006, making it possible for me to work on this project.

Introduction

A

world’s destiny hung in the balance. In the distant past a god had fallen to Q’zar, vanquished during a battle with other gods in the firmament. It was said that the god died, but his weapon did not. The Wardragon had the guise of a common mailshirt, but it was powerful, alive, and very intelligent. The people of Q’zar were spared the evil of the Wardragon for a thousand years, because it had been broken in the great fall, and many of its links scattered. Alas, learned but unwise war-lords and wizards such as the Preceptor and Fa’red began to gather the scattered links together, thinking to become masters of the restored mailshirt … but they did not understand the ways and deceits of the ancient and forgotten mindsmiths.

The Wardragon was not the weapon of a god, the Wardragon

was

the god. Anyone who wore the completed mailshirt would become its slave, not its master. Aided by the unlikely allies, Daretor and Zimak, the young sorceress Jelindel unwittingly achieved what the greatest of kings and sorcerers had been unable to do for a thousand years: she reassembled the Wardragon. Too late, she realised her mistake, and in a battle of magical energies that turned allies to traitors, and even swapped the minds of Daretor and Zimak with each other’s bodies, she destroyed the Wardragon and brought peace to Q’zar.

But the Wardragon was more resilient than Jelindel had realised …

Chapter 1

The Mailshirt’s New Host

R

as liked to watch the heavens, in fact he never tired of it. He knew the planets by heart and all the major constellations and even the names of some stars. He did not know what the stars were, but he thought they were pretty, and that seemed to be enough. Often though, he did have a glimmer of a deeper understanding of all things, and that greatly confused him. So too did tantalising glimpses of his wandering life and various wives and children. Truly there were things in his history that confounded him. It was as though he had led many lives all rolled into one.

He had sat out on the hillocks every night since he was young, tending various clans’ flocks and watching the stars. Only once had he lost a sheep and that had been to a wolf. He had tirelessly hunted down and killed the predator, chopping off its paws and bringing them back to Falser, the clan chieftain, to prove what he had done. Falser had laughed heartily and slapped the youth on the back several times, vastly amused by such single-mindedness in one so simple-minded.

Ras knew people laughed at him but his own spirit was so light that he never minded. Sometimes he laughed with them, which made them laugh even harder. He even felt sorry for them. They worked in the forests or the mines or sometimes in the city down by the sea, and seldom looked at the sky. They had families and friends, which he did not, but they stayed indoors at night and rarely acknowledged the heavens. Most of them could not name a single star. Only one old mage in those parts could do that, and lately even she had had trouble remembering all the astrological signs, patterns and events.

If the shepherd wished for anything it was for a spyglass. The old mage had described the wondrous device to him, and talked of how it brought the images of stars closer. She had even shown him one, and he had seen pockmarks on the moons of Q’zar, along with many more stars than the unaided eye could discern.

A shadowy nighthawk flew over the clearing where he watched the flock. Ras sighed. If only he could fly like the hawk. He would soar up into the sky and visit the moons and maybe even the stars. The old mage had once told him that the stars were very distant suns and that worlds like Q’zar went around them, just as Q’zar went around its sun. The mage had said that when he lay on his back on a hillock gazing up at a particular star, there was every possibility that another young man lay on his back on a planet circling that very star, gazing back at Ras. Ras liked that idea. It gave him a warm happy feeling but it also filled him with a vague unease at times. It was as if he should or did know all this but the knowledge was hiding from him.

Ras sat up straight. A shooting star streaked across the heavens. He quickly fumbled out his pouch, removed a tiny talisman made of eagle feathers and clay, and chanted a brief prayer that was more like a wish. He asked White Quell if he might one day travel to the stars.

As if in answer, the earth rumbled and the sheep began to bleat frantically. Ras was suddenly catapulted into the air. He hit the ground hard, the air knocked out of him. Then he was tossed up and down as the earth moved in sickening rolls beneath him. After what seemed a long time, but was probably only seconds, the rumble stopped. An utter silence fell. Sheep, insects, night birds, the night itself, all were hushed.

That was when Ras saw a bright gleam in a canyon several hundred yards away. It was like a golden fire, half glimpsed, or else like light gleaming off a warrior’s helmet. He quieted the flock, singing them a soft soothing song, then he set off into the canyon.

Even without illumination he rarely stumbled or put a foot wrong. Ras knew these hills the way a blind man knows his own house. A thick cloud of dust from an avalanche hung in the air. Ras could smell it, taste it. It got into his hair and clothes. He coughed several times. At last he came to the point where he felt sure he had seen the light, but there was nothing there now.

Ras turned in a full circle, and even stopped for a moment and stared straight up at the bright star, Angeera, as if it might reveal something. He took a step toward a precipice and as he looked back down, he was inexplicably bathed in golden light. He dropped to his knees, staring at a great fall of rock in the faint starlight. Exposed now, for the first time in who knew how long, were the jagged raw shoulders of the ravine, filled with fissures and pocked with holes. Halfway up, protruding from the disturbed earth, was what looked like a sleeve of golden links.

Muttering protective prayers, including one against acne, Ras made his way to the gleaming object. He was scared, but unable to stop himself. He took several slow measured steps closer, and knelt beside the artefact. He started digging. It took some time and he gashed his fingers on the sharp rocks, but he did not care. Here was a golden treasure, such as the old folk told of in their hearth stories. Princes and pirates were known to bury treasure, though Ras forgot that daemons and ogres did also. In his excitement, Ras could think of nothing, except a strange conviction that a star – one of those golden suns the old mage spoke of – had fallen from the sky and become buried in the earth.

Ras continued to dig.

When he had scooped out a sizeable hole, he sat back on his haunches and marvelled at the thing he had uncovered: a glorious mailshirt, made of thousands of tiny links, and so beautiful it made his heart ache. Even in the dark it glowed, as if there were life in it.

Without hesitation, the awestruck youth pulled the mailshirt on over his own ragged poncho. Childishly pleased he gazed down at himself, admiring the splendid figure he cut.

Then slowly his expression changed.

There was much grumbling in the encampment and little discipline. Fires burned brightly, often with no attempt to conceal them, and the voices of men carried far on the night air. Kaleton, a lieutenant to the warlord, strode angrily between the tents, a rage building inside him, yet he could say nothing. Here sprawled the ragged remnants of a once great army, the imperial guard of the Preceptor himself. It had once been a force which none could match.

Now it crouched in barren foothills, drinking the bitter local wines, its collective belly rumbling with hunger and discontent. Each night more and more soldiers deserted, and there was little the commanders could do. Kaleton had his hands full just trying to stop the Preceptor making an example of deserters caught in one of the local towns. The Preceptor believed that terror would reunite his fast dwindling army. But Kaleton knew that nothing would shatter the army’s fragile loyalty faster.

For now it was best to turn a blind eye, let the deserters go, and hope that most would come back when the warmer weather returned and good pillaging was to be had once more. Though that possibility was also slim.

The Preceptor’s time had come and gone, it seemed, and though he had grabbed the sword of fate in a mighty two-fisted grip, he had not held it for long. He had been bested by a slip of a girl. A girl who had turned out to be a very powerful archmage, though that did not assuage the insult.

Kaleton grunted sourly. He had stayed with the Preceptor longer than any other, his loyalty – though constantly tested – a thing of puzzlement to those who left. Sometimes even he was puzzled. Sometimes he had to make himself remember.

The Preceptor had given him back his honour, and that was no small thing.

Kaleton came to the north-east perimeter and noted, wearily, that the watch was asleep. He booted the man’s legs and watched with little satisfaction as the sentry leapt to his feet, cursing. The man fell silent when he realised who stood before him.

‘I was just resting, sir.’

‘You were asleep, Cullen. If I find you thus again I will make an example of you. Understood?’

‘Right you are, sir,’ the man grunted. ‘Keep your eyes open, man. What kills the rest of us will kill you first.’

Kaleton strode away into the dark. He found the other sentries awake, though sullen and listless and unconvinced there was a need for such watchfulness. Who would attack them here? Their worst enemies were boredom and lice. It was a standing joke in the encampment that if they could but enlarge the daemonic lice to the size of oxen and fit them with swords they would have an army nobody could beat.

In a square tent made of canvas and fur sat a man of middle years. Once known as the King of Kings, his hair was iron grey and his hawkish face sharp and angular, and badly scarred from battle. He was tanned the colour of old leather and wore a campaign tunic, stained boots, and breeches that had once been as soft and supple as kid gloves. A short cape embroidered with filaments of gold and silver thread spoke of better days, as did the jewelled goblet from which he drank.

‘More!’ He slammed the empty goblet on the folding table where a map was spread. Dark red wine spattered across it like a trail of blood.

A young lackey hurried in and refilled the Preceptor’s goblet. In his nervousness, the youth stumbled and a splash of wine spilled down the Preceptor’s front. The warlord’s hand flashed out and drove a parry-hilt knife into the boy’s arm. Real blood spattered the map this time. The boy screamed, clutching the knife, and stumbled back.

‘Imbecile!’ growled the Preceptor drunkenly. ‘Now get out.’

Kaleton entered, sized up the scene at once, and scowled. He called to one of the guards, ordered him to take the boy to the hospital tent and have him attended to. When they were gone, he turned expressionless eyes to the Preceptor.

‘No wonder you have trouble keeping servants.’ Kaleton straddled a chair. He eyed blood on the map and thought it an ill omen.

‘What?’ muttered the Preceptor.

‘Why did you stab the boy?’

‘Stab who? Talk sense, man.’

Kaleton’s neck ached. He tilted his head to the left then snapped it back. There was a sharp crack, and he felt some of the tension he had been feeling drain away. There was no point trying to reason with the Preceptor when he was in this state. Indeed, in some ways, the Preceptor he knew was not in this tent. The man before him was a shadow of that other man, the fierceness less, the focus blurred. And yet his next words surprised Kaleton, suggesting that he was not as drunk as he seemed.

‘How many asleep this time?’

‘One.’

‘Hang him.’

‘We have too few guards already. Hang one, and others will desert while they should be guarding you.’

‘You’re getting soft, Kaleton. Nothing like a hanging to smarten the men up, keep them focused.’

‘The men must be fed, Preceptor, and paid. Winning the occasional battle and having a few villages to burn and women to ravish might help, too. Without that, you will soon have no men to hang, knife, or put to sleep with speeches.’

The Preceptor eyed Kaleton. For a moment Kaleton wondered if he had gone too far. Bluntness was a virtue, he believed, and yet –

The warlord burst out with a braying laugh that was oddly infectious, like the laughter of children. He clapped Kaleton on the back, then hunched over again, bitterness returning as quickly as the laughter had come.

‘How many will we lose tonight?’ the warlord asked.

‘A score, perhaps. Another month and we will be down to you and me. Then we can pack up and go home.’

‘Home?’ the Preceptor mumbled softly. ‘Where is that, Kaleton? I seem to have misplaced the address.’

‘There will be better days, as long as we –’ Kaleton stopped and turned.

There was a commotion outside. They heard raised, angry voices, peremptory commands, then a hush. Kaleton drew his sword. The Preceptor stood, swaying, holding his goblet. If someone had come for his head, then he would greet him in a dignified fashion. If the truth were known, the Preceptor almost welcomed death. He was tired of fading slowly. It was better to fall in a spectacular defeat that would inspire legends, rather than a few ballads.

The shouts came closer. Kaleton stepped between the Preceptor and the tent flaps. The warlord noted this and, as always, wondered at the man’s fierce loyalty. Long ago the Preceptor had given Kaleton the chance to avenge himself, to unleash an appalling hatred. In some ways he had never fully recovered from that. Such were the things that fashioned men.