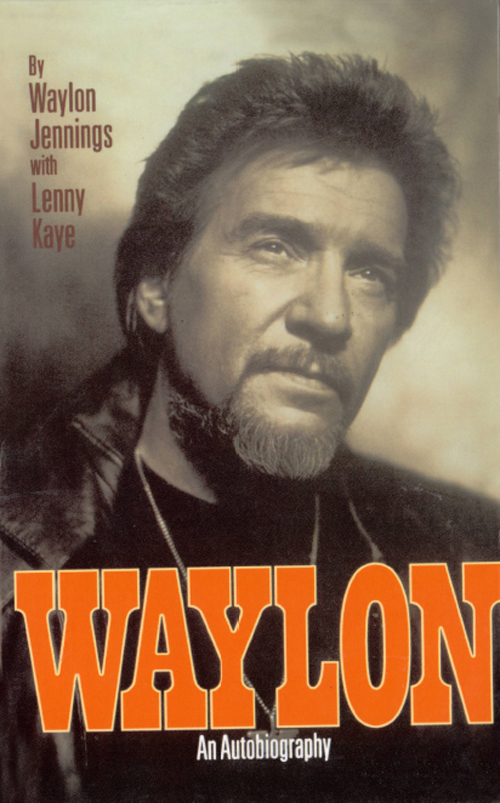

Waylon

Authors: Waylon Jennings,Lenny Kaye

Copyright © 1996 by Waylon Jennings

All rights reserved

Warner Books, Inc.,

Hachette Book Group, 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: June 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56237-9

Contents

CHAPTER 4: FROM NASHVILLE BUM …

CHAPTER 5: …TO NASHVILLE REBEL

CHAPTER 6: “THERE’S ANOTHER WAY OF DOING THINGS AND THAT IS ROCK ’N’ ROLL”

CHAPTER 11: WILL THE WOLF SURVIVE?

WAYLON JENNINGS AND JESSI COLTER: A SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

For Jessi

If you read this book you’ll know

why I’m blessed to know her

HERE’S TO MY LADY, SHE’S MORE THAN A WIFE

SHE’S BEEN MY BEST FRIEND THE BEST YEARS OF MY LIFE

THROUGH THE GOOD AND THE BAD TIMES, SHE’S MANAGED TO SEE

A LIGHT IN THE DISTANCE AND THE BEST SIDE OF ME

HERE’S TO MY CHILDREN AND THE LIFE YOU HAVE FOUND

I LEAVE A LOT TO LIVE UP TO AND A LOT TO LIVE DOWN

MY STRENGTH AND MY WEAKNESS—THE TRUTH AND THE LIES

HERE’S TO MY COMRADES THE WEAK AND THE STRONG

IT’S TIME WE STOPPED COUNTING THE RIGHTS TO BE WRONG

WE’RE EQUALLY GUILTY FOR THE TROUBLE WE’VE HAD

WE BRING OUT IN EACH OTHER THE GOOD AND THE BAD

I’M STILL A DREAMER AND DREAMERS SURVIVE

AND I’LL KEEP CHASING RAINBOWS EACH DAY I’M ALIVE

BELIEVING IN PEOPLE AND KEEPING A LIGHT

FOR WAYFARING STRANGERS AND SHIPS IN THE NIGHT

© 1991 WAYLON JENNINGS

N

ighttime. Highway. I’ve seen this unraveling dream many times before, endless distance flicking white stripes on a black top.

Riding along.

I sit in the shotgun seat, arms folded across my chest like an old Native American, staring out at the exit signs. Norths

and souths. Backs and forths. Crisses and crosses. A life in between.

It’s like a screen, that big bus window, especially in the dark. You can watch any movie you want, mostly your own, as you

roll past the side of the road. We’re coming up on Big Daddy Don Garlits’s hot rod museum, or the Club Risque, whose motto

is “We Bare All.” I-75. Must be somewhere outside Ocala, Florida. Could be anywhere.

Let me see that map. Jigger, you know of a Cracker Barrel near here? Maybe we should stop and grab some breakfast when it

gets light.

I’m enjoying this. You know how to get it out of somebody. Every time I talk to you, I come up with something else I remember.

Some of it’s not that pretty, but I’m proud of most of it.

There’s a lot to sort out. Put in perspective. I’ve been there, and here, and wherever I’ll be tomorrow. Sometimes I feel

like I’ve gone around twice over. You’re talking to a guy who never went to sleep. I’ve lived a couple of lifelines. Maybe

that’s why I don’t feel tired tonight. We can stay up late. Watch the road. Count off the miles.

You want to get started?

T

he storms boil up out of the west; a red-black cloud taking over the sky, streaming across the New Mexico border into Texas.

You can stand there and watch them coming at you, nothing to stop them on the high open plains, seventy, eighty, ninety miles

an hour, moving like a dark horse across the flatlands, bringing sand, and dust, and tumbleweeds. Always from the west.

I’ve seen chickens go to roost at noon, it’d be so dark. The wind howls through those old tar-paper houses, the sand sifting

across the road till you can’t see where the blacktop begins, and the grit gets in your teeth. Many a time I’d be going home,

running down the street, trying to beat the storm, and I’d have to stop and grab hold of a pole to keep from getting blown

over.

You look under your window, or beneath the door sill, and there’s a pile of sand seeping in, and fine dirt. It covers everything.

The sand drifts up against the fences as if it were snow. The wind that blows it circles town from the outside, driving back

along Bula Highway, then around to Spade Highway, Littlefield rising out of the whirling dust like a mirage.

“Lonesome,” Momma used to call the noise the wind made, and it haunts me to this day. It sounded like the end of time to me.

Sometimes I think I make music to shut out the wind, to find a place where the sands can’t touch, and the air smells sweet

and clear on a spring morning after the rain.

It rained a lot that spring I was born. More than eight inches fell in the two weeks before I arrived, bringing with it hopes

of a bumper cotton crop and the toil of replanting. The hail spared Lamb County, though it wreaked havoc north to Dimmitt,

east to Plainview, south to Lubbock. There was a shortage of laying hens. We were on the fringes, seven or so miles northeast

of Littlefield. On Tuesday morning, June 15, 1937, Momma went up to the main farm house, owned by a Mr. J. W. Bittner Sr.,

and birthed me. Daddy got to celebrate his first Father’s Day that Sunday.

My coming wasn’t recorded in the Lamb County

News

or

Leader.

Downtown, where Norma Shearer and Leslie Howard were starring in

Romeo and Juliet

and the society pages were all fussing about the Duchess of Windsor, they paid no notice to what was happening to us subsistence

farmers working the fields. Dirt-poor (we had the floor to prove it), we shared a two-room house with my uncles and aunts

and cousins. The bed was in the living room, and there was a kitchen. Twelve people; I don’t know how we did it.

At least that was a step up from the half-dugout my Uncle Bud lived in, by Hart Camp: a roof over a cellar. Momma and Daddy

first got married out there, maybe ten miles from Littlefield, a town that had a school house, a cotton gin, a grocery store,

and not much else. Don’t blink, or you might miss it.

They’d met at a dance, William Albert Jennings and Lorene Beatrice Shipley. He was a musician in a one-man band, just him

playing harmonica and guitar. She couldn’t have been more than fourteen, from Love County, Oklahoma. She danced every dance.

Momma used to get mad because Daddy didn’t know how to dance, and she’d have to hold the harmonica for him in his mouth—they

had no holders in those days—and wouldn’t get to dance every set.

They got together in 1935 and moved in with Grandpa Jennings. There were sixteen people living in their two rooms, up in a

little house on a hill, though, if truth be known, it was more like a bump on the earth. Nobody had any money. They papered

the walls with newspaper, pasting it up with flour and water. They did it to stay warm; for insulation, not for looks. It

covered up the cracks in the wall.

My daddy was the hardest-working man you ever saw. He did everything at one time or another. He worked in the fields, he ran

a creamery, he owned a gas station, he drove a fuel delivery truck. One time he broke his back; he’d been working over in

Hobbs, New Mexico, and a piece of lumber fell on him. He got out of the hospital, in a back brace, and immediately went out

and pulled cotton. It hurt so bad he had to do it on his knees, but he wanted to get us money for Christmas.

It was never easy for our family, even after Momma and Daddy moved over to the Bittner farm. One time I remember my dad setting

in the chair and crying. His head was in his hands. I couldn’t have been more than two years old because my brother Tommy

was still a babe-in-arms. (I’ve always had a good memory, even that early, and I can go as far back in time as when I was

bouncing in my jumper swing, reaching for my dad’s guitar.) Daddy had worked sunup to sundown, and we still didn’t have nothing

to eat. A dollar a day was what he made.

Yet it wasn’t a rare thing when he laughed. He laughed a lot. He’d tease us unmercifully and give us all nicknames. Daddy

called me Towhead, because my hair was light colored, or Little Wart. When he smiled, the whole room lit up. Kids trusted

him. My daddy could walk up to any child, and they might be bashful and shy and turning away. In a minute they’d be right

over cuddling next to him. He was constantly joking.

Daddy finally got himself enough money to buy him a truck. He had a ’41 Ford, short bed; a bobtail, they called them. Grandpa

Jennings had traded in his span of mules for a tractor and moved out by Morton, west of Littlefield, near Enochs. He had eighty

acres; that was about all you could handle in those days. We were doing all right, even if Momma still tells the story of

how she had to put me up on the stove while she was cleaning the house to keep the rats from getting me. That’s kind of country,

isn’t it?

Saturday night, we used to sit on the Bittner farm and see the lights of Littlefield off in the distance. We grew cotton and

maize on the patch of land we worked. We were farm laborers, not even sharecroppers, and when Daddy got back from a day in

the fields, he had to milk about twenty head of cattle. On hog-killing day, we’d get out the ice cream freezer and break open

watermelons. Yellow meat watermelons. They’d weigh fifty or sixty pounds, and nothing tasted closer to heaven.

They were originally going to name me

Wayland

: “land by the highway.” It’s no wonder I’ve spent my life on the road. Momma wanted to call me

Galen,

and my grandmother had a boyfriend that she was going to marry who had died of some disease, and his name was Wade. Daddy

thought I should have the initials W.A., which was traditional for the oldest through the Jennings. The first ones that ever

migrated to Texas were William Albert and Miriam.

So it came down to Wayland Arnold. But when a Baptist preacher stopped by to visit Momma, he said, “Oh, I see you’ve named

your son after our wonderful Wayland College in Plain-view,” so she immediately changed the spelling to Waylon. We were solidly

Church of Christ, saved by baptism instead of faith. She never got around to switching it on the birth certificate. I still

hate my middle name, and for a while I didn’t like Waylon. It sounded so corny and hillbilly, but it’s been good to me, and

I’m pretty well at peace with it now.

Littlefield is on the cap rock, right at the foot of the Great Plains as they stretch through Denver all the way north to

Canada. It’s up about four thousand feet, but it’s so flat your dog could run off and you could watch him go for three days.

They say you can stand in Littlefield and count the people in Levelland, twenty miles away. There’s nary a tree anywhere;

and the sky surrounds you like a huge blue bowl. At night it’s almost like you’re being sucked up into the stars.

When you’re born in Texas, you think that you are a little bit taller, a little bit smarter, and a little bit tougher than

anybody else. It’s a country unto itself, it really is. In fact, it was the only place that was a country before it was a

state, and the people who live there still feel that way. My wife, Jessi, hit it right on the head when she said “They think

the rest of the world is overseas.” Of course, she’s from Arizona. She knows what it’s like being around cowboys.

We could just dream about being cowboys. For us, life on the farms was all we could look forward to. Littlefield is part of

the cotton belt, and it sits astraddle the line between dry-land farming on the west side and wet irrigation to the east.

We pulled cotton all around Littlefield, getting up at four in the morning to be in the fields before dawn. It would already

be so hot and dry that the gnats would be swarming at your eyes, trying to get at the moisture. By the time the day was too

hot for them, we’d be halfway down a row, hunched over, dodging the snakes, pulling the bolls and chopping at them, trying

to get to the water jar we had waiting at the end of the row. We were able to stand up when the cotton was high, and virtually

stooped in half to reach the low.