We Are the Rebels (8 page)

Authors: Clare Wright

As early as March 1853, contemporary observers like James Bonwick were already commenting

that the diggings were attracting women like ants to honey. In just two days he counted

one hundred and twenty ladies, going up either with or to their lords of the pick

and cradle

.

Bonwick called it a phenomenon, this

feminine Exodus from our townships

. He also

noted that

some husbands have taken uncommon care to prepare for the coming of their

better halves

by upgrading their accommodation: moving out of their tents and into

log cabins with stone chimneys and floor coverings and, in one case, an iron bedstead.

The diggers' wives accompanied them not just to keep families intact, or to avoid

being left behind, but also in a genuine spirit of exploration. When James Watson

determined to go to Ballarat, his wife Margaret, who had already survived

several

trials with James and their children,

decided that this was one more adventure for

her

. Emily Skinner knew that her husband William

would not go if I objected very

much, etc. but

, she reasoned,

what a much better chance we should have of getting

on

[together]. After thinking and talking it over a little, the couple decided that

William would go on ahead, make enough money to build a comfortable tent home, then

send for Emily to join him. This all happened surprisingly quickly.

There were hundreds of lone women, too, on the road to Ballarat, some joining (or

searching for) absent husbands or connecting with other family, some making their

own way in the world.

Emily Skinner met

two stout young women

on her journey to the Ovens.

They told me

that they had many offers of a place [in Melbourne], as it was hard to get servants

,

wrote Emily in her diary,

but the girls were determined to go to the diggings, where

high wages and easy times awaited them

.

Mary Bristow, 42 and unmarried, was keen to go to the diggings

as a kind of bivouac

(or camping trip) and found three other young women to accompany her. The first night

the women slept in a covered dray, but it rained in torrents.

I don't think I closed

my eyes

, wrote Mary. That first day, they walked 22 kilometres, the next nearly 40.

The women wore veils and large bonnets and never ventured out in the middle of the

day; it was

too dangerous to expose [ourselves] to the sun's burning rays.

Other

people, however, were not a threat. Mary was relieved to note that

there is always

due observance of respect

from the men in their travelling company. Ladies could

walk or ride long distances unattended and have nothing to fear.

I have never been

so happy or free from care

, she wrote.

Mrs Elizabeth Massey also found a change in herself on

the road to Ballarat. Back

in England Mrs Massey had been married only a few weeks when her new husband

unexpectedly

called on

her to accompany him to Australia.

Disgust

, she wrote in her memoir eight

years later,

indeed is not a word strong enough to express my feelings at the moment

.

On arrival in Victoria, the Masseys went straight to the diggings to avoid the

filth,

flies and expense

of Melbourne.

But on the road, Mrs Massey felt joyfully off the leash. What had initially settled

upon her as a black cloud of misery now seemed like

a party of pleasure

. In common

with other women who started out thinking they were on a highway to hell, she happily

discovered herself on a path to unexpected release.

It is often said that escapeâmore than simple gold-lustâstimulated men's rush to

the diggings. These were, as one writer put it,

the days when men broke their bonds

and dreamed of marvellous things to come.

And it is usually implied that the bonds

they wanted to break included nagging women and their bawling brats.

But it's clear that many women also harboured their own aspirations of escape, not

necessarily from spouses and children, but from the tedious restrictions of their

lives. In particular, many educated and refined women (in the words

of one emigrant

who eloped with her brother's tutor and emigrated to Victoria)

thought the ease

of their English life well left behind them

. Polite conventionsâhigh teas and calling

cards and corsets and crinolinesâwere like shackles for many nineteenth-century

British gentlewomen. It cost a lot of effort and anxiety to keep up appearances.

Years later Mrs Massey, who spent two years on the diggings between 1852 and 1854,

would write

I look back with a grateful heart to my gipsy life

.

Refugees from convention were joined on the road by fugitives from the law. The goldfields

frontier was a good place to disappear in search of a fresh start. The presence on

the goldfields of ex-convicts from Van Diemen's Land (known as Vandies) became a

hot political issue after 1853, but there were other kinds of trouble you might want

to leave behind. An unwanted pregnancy, for example. A âMiss Smith', with her fatherless

baby, could be reincarnated on the diggings as âMrs Smith', who'd lost her (fictitious)

husband in a mining accident or maritime mishap.

For it was no joke to be an unmarried mother. There are reports of many a young woman

who killed or abandoned her newborn in an attempt to hide the evidence of âher' sin.

On 31 October 1854, for example, the Colonial Secretary was informed that a one-month-old

child had been found in the grounds of St John's School on the corner of Elizabeth

and La Trobe streets. The baby

was in good health

and was wearing a long white frock

and wrapped in a blue and green checked shawl. The Government Gazette posted a reward

for the apprehension of the mother.

The Police Gazette is also full of reports of female runaways. On 27 February 1854,

information was distributed about one Sarah Wilson, who had left the hired service

of Mr

Smith in Collingwood before her contract expired. Wilson was nineteen years

old and just under five feet (about 150 centimetres) tall, with a dark complexion

and small, regular features.

She has left her clothes behind her and has no relatives

in Melbourne

, noted the Gazette.

CORSETS AND CRINOLINES

Can you imagine removing your ribs for the sake of fashion? That's just what some

women did to achieve the perfect nineteenth-century feminine figure: a tiny waist

and ample hips. You also needed a tightly laced corset. (One woman called corsets

those vile instruments of torture

.) Over this you wore a crinoline: a hooped frame

designed to support skirts in a bell-like shape.

Corsets meant you couldn't breathe and crinolines meant you couldn't walkâand sometimes

they caught fire. There were women who died of their skirt injuries.

In 1848 a group of middle-class women, headed by an indefatigable mother of six named

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, met in Seneca Falls, New York, to address the problem of

women's social and political oppression. As part of their campaign for women's emancipation,

including the right to vote, these women argued that political freedom should be

expressed by freedom from corsets and crinolines, which not only distorted women's

bodies but also ruined their health. From this emerged a new ârational dress' outfit:

a long tunic and billowing pants gathered at the ankle. The outfit was known as

the Bloomer costume, after magazine editor Amelia Bloomer, who publicised it, and

it became a must-have fashion item among women's rights advocates in America and

England.

In March 1854, Ann Plummer escaped from the residence of her husband in Fitzroy Crescent.

Ann had been tried for an undisclosed offence at the Central Criminal Court in 1849

and given a fifteen-year sentence, to be served at the premises of her husband. Ann

was described as aged 25 years and five foot one inch (152 centimetres) tall, with

a

fresh complexion, brown hair, blue eyes, native Burnley, nose has been smashed

.

You could make an educated guess about what she was running away from.

Clearly, women had many practical reasons to seek the new adventures offered by the

goldfields. There was safety in numbers, and as the travellersâmale and femaleâreached

the end of the road, liberation was finally in sight.

You could hear Ballarat before seeing it.

When journalist Thomas McCombie arrived in 1853,

A confused sound like the noise

of a mighty multitude broke upon our ears and a sudden turn of the road brought us

in full view of Ballarat. I freely confess,

he wrote,

that no scene have I ever witnessed

made so deep and lasting an impression on my mind.

Horse bells jingled, whips cracked, people shouted and parrots screeched. Thousands

of dogs chained outside tents and mine shafts barked constantly. One newcomer, schoolboy

John Deegan, described

the uproarious blasphemy of bullock driv

ers

as their swearing

echoed across the basin. Years later he wrote of

that vague, indescribably murmurous

sound, which seems

to pervade the air where a crowd is in active motion

. The feeling would never leave

him. It was like a

genuine fairy tale

.

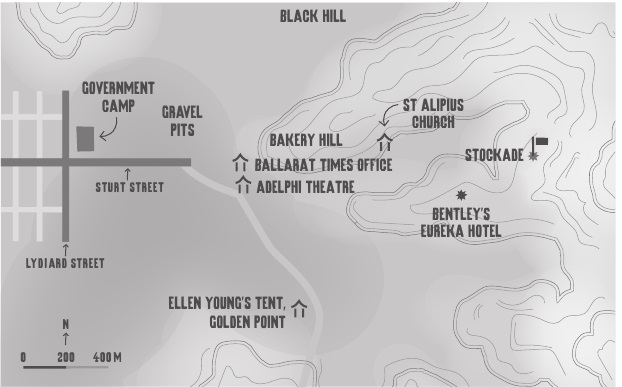

Ballarat, 1854

The bewitching effect was particularly astonishing for travellers who arrived at

night. Henry Mundy, then a 20-year-old shepherd, walked from Geelong to Ballarat

to find his fortune. Standing on the ridge, he could see only the twinkle of a thousand

campfires, like a mirror image of the night sky. Yet the noise, he later recalled,

was

indescribable

.

During the evening meal

the talking and yelling was incessant

. Later, there were

guns and pistols firing, a release of the day's pent-up emotion, and everywhere the

continuous yowling and barking of the dogs. After the ritual gunfire stopped,

accordions,

concertinas, fiddles, flutes, clarionettes, cornets, bugles, all were set going each

with his own tune

. The effect, said Mundy, was

deafening

.

In late 1853 Ballarat was a sprawling tent city. As the travellers arrived they saw

before them the vast diggings of East Ballarat, where a creek wound through a valley

of low mounds and hills. Bakery Hill rose in the distance. Perched above the diggings

was the Camp, home to the officers of the Gold Fields Commission: the police and

public servants who ran the place. Thomas McCombie called them

the aristocracy of

the canvas city of Ballarat

. Nestled beside the Camp on a neat grid of streets was

a tiny new township of stores and homes. Some of them were even built from timber.

Encircling all this was a ring of green, the last remains of the thick scrub that

had once covered the entire basin.

The diggers

, observed English journalist William

Howitt,

seem to have two especial propensities, those of firing guns and felling

trees

.