Welcome to Your Brain (18 page)

Read Welcome to Your Brain Online

Authors: Sam Wang,Sandra Aamodt

Tags: #Neurophysiology-Popular works., #Brain-Popular works

and focus on the task at hand in spite of distractions. Problems with executive function begin later, for

most people when they reach their seventies, and include the deterioration of basic functions like

processing speed, response speed, and working memory, the type that allows us to remember phone

numbers for long enough to dial them. Difficulties with executive function, along with navigation

problems, explain why your grandfather doesn’t drive as well as he used to. (It’s probably just as

well that he can’t remember where he put his car keys.) Some sensory inputs decline with age, like

the hearing problems we discussed in

Chapter 7.

It also gets harder to control your muscles, though

it’s not clear whether this problem lies with the brain or with the aging body.

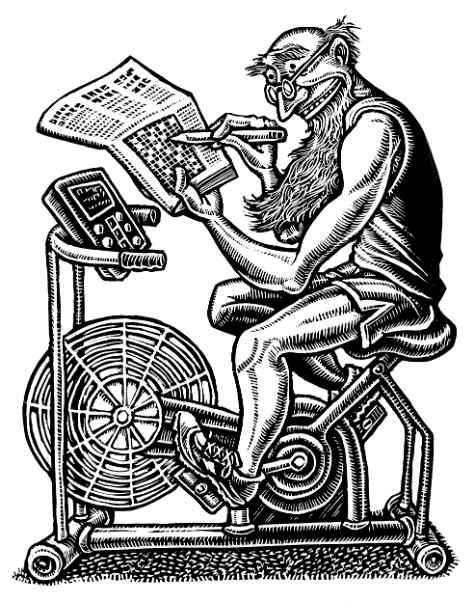

Practical tip: How can you protect your brain as you get older?

The most effective approach to keeping your brain healthy with age turns out to be

something you probably wouldn’t expect: physical exercise. Neurons need a lot of support

to do their jobs correctly, and problems with an aging circulatory system can reduce the

blood supply that brings oxygen and glucose to your brain. Regular exercise, of the type that

elevates your heart rate, is the single most useful thing you can do to maintain your

cognitive abilities later in life.

Elderly people who have been athletic all their lives are much better at executive-

function tasks than sedentary people of the same age. This relationship could occur because

people who are healthier tend to be more active, but that’s not it. When inactive people get

more exercise, even in their seventies, their executive function improves in just a few

months. To be effective, exercise needs to last more than thirty minutes per session and

occur several times a week, but it doesn’t need to be extremely strenuous. (Fast walking

works fine.) The benefits of exercise seem to be strongest for women, though men also

show significant gains.

How does exercise help the brain? There are several possibilities, all of which could

contribute to the effect. In people, fitness training slows the decline in cortical volume with

age. In laboratory animals, exercise increases the number of small blood vessels

(capillaries) in the brain, which would improve the availability of oxygen and glucose to

neurons. Exercise also causes the release of growth factors, proteins that support the

growth of dendrites and synapses, increase synaptic plasticity, and increase the birth of

new neurons in the hippocampus. Any of these effects might improve cognitive

performance, though it’s not known which ones are most important.

Beyond normal aging, exercise is also strongly associated with reduced risk of

dementia late in life. People who exercise regularly in middle age are one-third as likely to

get Alzheimer’s disease in their seventies as those who do not exercise. Even people who

begin exercising in their sixties can reduce their risk by as much as half. See you at the gym!

Specific changes in the brain’s structure and function are associated with the deficits in memory

and executive function during aging. The hippocampus becomes smaller with age, and this decrease in

size correlates with memory loss. Similarly, the prefrontal cortex is important for working memory

and executive function, and it becomes smaller with age as well.

Contrary to what you might imagine, brain shrinkage with aging is not due to the death of neurons.

As you age, you do not lose neurons. Instead, individual neurons shrink. Dendrites retract in several

regions of the brain, notably parts of the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. The number of

synaptic connections between neurons in these areas decreases with age in most animals that have

been examined. Older animals also have specific deficits in synaptic plasticity, the process that

drives learning (see

Chapter 13)

, but only in certain parts of the brain.

On the other hand, some brain functions are not influenced much by age. Verbal knowledge and

comprehension are maintained, and may even improve, as we get older. Vocabulary is another area

that tends to be spared by aging. Professional skills are typically resilient, especially if you continue

to practice them. Similarly, people who practice physical skills regularly are more likely to maintain

them; in this case, there is some evidence that experts develop new strategies for well-rehearsed

tasks to compensate for cognitive decline as they age. In general, anything that you learned thoroughly

when you were younger is likely to be relatively spared by aging.

Did you know? I’m losing my memory. Do I have Alzheimer’s disease?

If you forget where you put your glasses, that’s normal aging. If you forget that you wear

glasses, then you probably have dementia. A disorder like Alzheimer’s disease, which

causes two-thirds of the cases of dementia, is not an extreme example of regular aging, but

involves deterioration of specific brain regions along with symptoms that never occur in

normal aging. People with advanced dementia cannot remember important incidents from

their own lives and may not even recognize their spouses or children.

The strongest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is simply age. The incidence of the

disease doubles every five years after age sixty, reaching almost half the population by age

ninety. Statistical estimates suggest that about 75 percent of people in the U.S. would

develop Alzheimer’s disease if we all lived to be one hundred. As the world’s population

ages, dementia is becoming more of a problem; its current incidence is twenty-four million

people worldwide, and the number is expected to increase to eighty-one million by 2040.

Genetic factors have a considerable influence on your susceptibility to dementia,

particularly the age of its onset. About a dozen genes have been identified as risk or

protective factors, but one of them, the ApoE gene, has a stronger effect than all the rest put

together. The average age of onset is about fifteen years earlier for people with two copies

of the risky form of the ApoE gene compared to people with the protective form of the gene.

Many of the lifestyle factors that influence brain function during normal aging are also

relevant to Alzheimer’s disease. As discussed above, exercise is strongly protective. Other

factors that correlate with a reduced chance of dementia include education, regular

consumption of moderate amounts of red wine (but not beer or hard liquor), and the use of

over-the-counter pain relievers with anticlotting effects, like aspirin and ibuprofen. In

general, it seems as though improving your brain’s ability to function tends to improve its

resistance to a variety of problems, including dementia, late in life.

The good news is that older people have one important advantage over the young: a better ability

to regulate their emotions. The frequency of negative emotions decreases with age until it levels off

around age sixty, while positive emotions remain about the same. As people get older, they become

less likely to perceive negative events or to remember those from their everyday lives or the past.

Negative moods pass more quickly in older adults, and they are less likely to indulge in name-calling

or other destructive behavior when they’re upset.

There are also some more general changes in brain activity during aging. Older adults tend to

activate more distinct brain areas than young adults while performing the same task. Compared with

young adults, older people also tend to show lower overall brain activity and use areas on both sides

of their brains instead of just one. These findings suggest that people use their brains differently as

they age, even though they may perform a task equally well. This may be because older people learn

to use new parts of their brains to compensate for problems elsewhere.

Cognitive decline at a certain age is not inevitable. Your lifestyle has a lot of influence on your

abilities late in life. We mentioned before that people tend to retain skills and knowledge they learned

thoroughly when they were younger. Perhaps for this reason, educated people have better cognitive

performance with age than less-educated people. Another way to keep up your cognitive performance

is to have intellectually challenging hobbies. This effect is more pronounced in blue-collar workers

than in highly educated people, perhaps because educated people tend to work in jobs that involve

considerable intellectual stimulation.

Did you know? Are you born with all the neurons you’ll ever have?

Many of us learned in school that the brain is unique because, unlike other organs of the

body, it doesn’t add new cells over its lifetime. Scientists believed this for many decades,

but new discoveries indicate that it’s not true. Both animal and human studies show that a

few parts of the brain do produce new neurons in adulthood, though this ability declines

with age. In particular, new neurons are born in the olfactory bulb, which processes smell

information, and in the hippocampus. More of these new neurons survive and become

functional parts of the brain’s circuitry in animals that are learning or animals that exercise

a lot. At present we don’t have much information on the environmental conditions that

encourage this process.

Attempts to improve cognitive skills in the elderly through training have yielded mixed results.

Although most training programs work to some extent, the gains tend to be specific to the trained task,

leading to little improvement in brain function across tasks. On the bright side, though, these gains can

last for many years in some cases. One way to get around the problem of task specificity is to practice

a variety of skills—either formally or by staying involved in several hobbies or volunteer projects in

retirement. Our strongest suggestion, though, is to exercise consistently (see

Practical tip: How can

you protect your brain as you get older?

), as keeping your heart in good shape has general positive

effects on the brain, particularly on executive function, which helps you perform a variety of mental

activities.

It seems that the Greeks were onto something when they recommended that people aim for a sound

mind in a sound body. You’ll be doing your best to keep your brain healthy if you keep some of both

types of activity in your life. If you already get enough exercise, add an intellectual hobby like

learning a new language or playing bridge. If you have an intellectual job, get a physical hobby like

playing tennis or jogging. In general, having both physical and intellectual interests is the best

protection against losing brain function with age.

Is the Brain Still Evolving?

New technologies in transportation, medicine, electronics, communications, and weaponry have led

to tremendous changes in our lives and habits over the last hundred years. Public health initiatives,

vaccination, and sanitation have increased life expectancy by decades. Jet travel and communication

have made the world a smaller place. Telecommunications and the Internet have made unprecedented

amounts of information available to anyone, almost anywhere. Mass entertainment, with its constant

stimulation, has become a major part of daily life. These advances have changed how we experience

the world. Is the human brain also changing to keep pace?

Brains can change over time in two ways. First, the environment can influence brain development,

leading to rapid changes, even within a generation. Second, there is biological evolution, which

requires at least one generation to cause changes.

Rapid changes can be driven by the direct biological effects of a new environment. For instance,

children growing up in preindustrial England faced challenges such as disease, nutritional

deficiencies, and difficult field labor. After the Industrial Revolution, these were replaced by

problems such as factory labor conditions, urban living, and pollution. Living conditions changed

again and again through the Edwardian era, World War II, and the Cold War. Now children in

developed countries grow up with standardized schooling, better nutrition, mass entertainment,

computers, cell phones, and other technology.

Some of these changes in environment may underlie the Flynn effect, a phenomenon first noticed