When All Hell Breaks Loose (15 page)

Read When All Hell Breaks Loose Online

Authors: Cody Lundin

"He who does not economize will have to agonize."

—Confucius

A

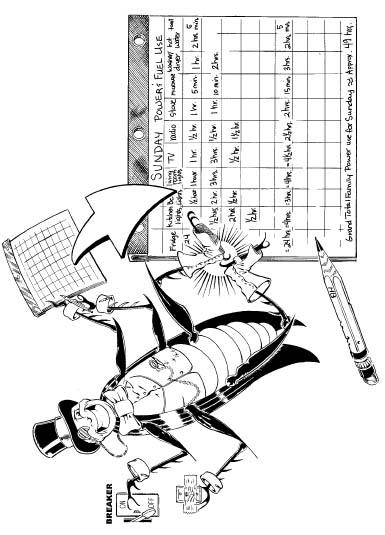

ssuming that you live in a metropolitan area, as 80 percent of our nation does, a large part of your survival plan will focus upon your home. If you're living on "grid power," provide fun for the entire family by finding the main breaker and turning it off. (Tell your family first what you're trying to accomplish). Folks living in apartments or other places where the neighbors would frown upon your little game can simply duct tape switches and appliances as reminders that they no longer work. Try this exercise some evening and see if you and your family can sense the feeling that someone has you by the groin. Most families quickly realize that their world as they know it can be brought to a standstill in the blink of a breaker. Like Alcoholics Anonymous, the first step in the healing process is to realize that we have a problem. But in this case, we're not powerless to do something about it.

Another cool exercise to find out how much power and fuel your family uses is to compile a list. The list should include all major appliances or items that require electricity or fuel such as propane or natural gas that your family uses on a daily basis. For example, the word "refrigerator" stands for the refrigerator, the word "television" represents the television and so on. Each time a family member uses an item on the list, they put a check mark beside the item. This method is more effective if everyone writes down the amount of time the item was used. If the television is checked off, write down how long you watched TV after the check mark. Using the check mark system allows family members to at least see how many times an appliance has been used (as they put the check mark by the appliance before they use it), in the event they forget to jot down how long the appliance was on after the fact. You might also have a list for items that are used every week or two. If your family is honest with itself, it won't take long to pick out the high-use items. Extending the exercise a full week, photocopying the original checklist so that each day has a fresh page upon which to record your day's consumption, will give you a good average to work with regarding your family's fixation with its furnishings.

Next, have a family meeting (remember consensus decision-making, if applicable) and carefully look over the high-use items in the household. What stuff has the most check marks beside it and how long was it used? Decide for your family what are non-negotiable, high-need items. I would recommend breaking this into two parts. The first list should have items that dictate the very survival of your family. In essence, your family would die in a long-term survival situation without these items. Anticipating the duration of your family's mock survival scenario is paramount to what and how many supplies you will need. Only you know if more supplies will be required for your situation.

Part two includes items that, while not truly needed for base survival, would be nice to have around to keep the kids from crawling up the walls. This list might include a few high-use items from the main list that add to the family's sense of calm by promoting psychological comfort. If television is prominent for your tribe, and you don't have a small, battery-operated TV (as if full programming would be up and running in a serious emergency), consider instead the ultimate goal of TV. While it can provide information, TV typically provides entertainment, but so do board games, and with fewer moving parts and less energy consumption.

Listing what your family actually uses each day and how long they use it will hammer home the truth about what they deem important in your household. Without this written evidence, you will be far less likely to accurately assess your family's needs and wants, and what will push their buttons when they are deprived of the furnishings they love so much.

Gimme SHELTER!

"If design, production, and construction cannot be channeled to serve survival, if we fabricate an environment—of which, after all, we seem an inseparable part—but cannot make it an organically possible extension of ourselves, then the end of the race may well appear in sight."

—Richard Neutra,

Survival Through Design

T

he optimum ambient temperature in which human beings are able to maintain core body temperature without stress is 79 to 86 degrees F (26 to 30 degrees C). Although the modern home now serves many purposes, physical and psychological, a home used to have one main priority. It matters not if your home is a mansion or a shack for this purpose. Both the mansion and the shack are simply shelters, and a shelter's main purpose in the past was to act as an extension of clothing to help thermoregulate the core body temperature of its occupants. I don't care how much money you've dumped into your shelter to compete with the Joneses, if it's too hot or cold inside, you'll be miserable. This almighty god called "room temperature" is a phenomenon so common and taken for granted that its importance to comfort and happiness has been completely overlooked by modern urbanites. It's only when the invisible switch of room temperature clicks off that people realize how dependent on the grid they have become.

According to Tony Brown, founder and director of the Ecosa Institute, Americans use more than 30 percent of the country's total energy budget to heat and cool their homes. This wasteful blasphemy should hammer home the point that stabilizing the inner temperature of the home ranks high on the list of priorities for all Americans. It's a blasphemy because there are many alternative building and common-sense options for builders and homeowners alike that severely reduce or all but eliminate the need for heating and cooling the home with outside resources. The Ecosa Institute is a sustainable design school for architecture students that teaches alternative methods of design, construction, and energy efficiency. It is part of the growing tide of people worldwide who know there are better options for building smart, efficient homes without pillaging the land. Imagine how much freer this nation and the world would be if common-sense building alternatives to promote energy efficiency were actively promoted by the world's governments. What if we eliminated even half of the above percentage of our nation's energy dependence by simply building or modifying current homes to make better use of free energy sources and conserve the ones they use? Luckily, we don't have to wait for status quo politicians who seem to be more interested in keeping their job than doing their job.

The Self-Reliant Freedom of Good Design

"M

Y PRECEPT TO ALL WHO BUILD IS, THAT THE OWNER SHOULD BE AN ORNAMENT TO THE HOUSE, AND NOT THE HOUSE TO THE OWNER

."—C

ICERO

In a modern outdoor survival situation the most common way to die is to succumb to

hypothermia

, low body temperature, or

hyperthermia

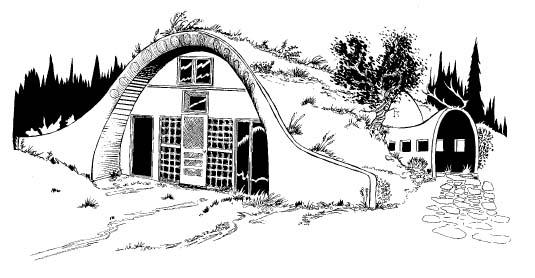

, high body temperature. Knowing this, and knowing that this country has become a slave to foreign energy in order to have a comfortable living room, I wanted to design a home that would thermoregulate its own core body temperature, and I have. While my home looks unconventional, the basic concepts that I've incorporated to achieve energy freedom are orientation, thermal mass, and insulation. These common-sense concepts can be applied to any home regardless of the materials it's constructed from or how it looks.

It's winter in the high desert as I write this, and last night the thermometer outside read 9 degrees F (minus 13 degrees C), a bit colder than typical and, ironically, part of the same storm system that left 500,000 people without power in the Midwest. Regardless of single-digit temperatures, my home remained a cozy 72 degrees F (22 degrees C), and it did so without using

any

conventional energy resources. I have no heating bills of any kind and I don't burn wood. My home is heated entirely by the free clean energy of the sun, a phenomenon commonly referred to as "passive solar." Along with orienting my home solar south, I have the proper square footage of windows to match the square footage of my home so that it doesn't under- or overheat. These windows let in shortwave radiation from the sun that soaks into my stone floor during the day. At night when outside temperatures dip, the stone floor, which is a great conductor of the sun's energy, re-radiates the stored sunshine, or heat, as long-wave radiation that keeps the house warm. Insulation and thermal mass help retain the heat throughout the night. The process starts anew the next day. Even though my home is dependent on the sun for heat, it's designed to retain this comfort for several days of cloudy weather or storms.

In the summertime, when outside temperatures hit triple digits, I enjoy inside temps in the high 70s (approximately 25 degrees C). I have no cooling bills of any kind. A simple roof overhang designed for my window height and latitude keeps the higher summer sun's rays from hitting the stone floor. My windows and doors are situated to take advantage of the prevailing weather patterns and the cooler nighttime breezes. In fact, the entire front of the house is a huge parabola that acts as a scoop to harness the dominant southwestern weather systems for optimal natural free ventilation when required. Once again, thermal mass and insulation keep out hot temperatures while maintaining the cooler inside environment.

I've utilized an open floor plan that allows natural light from the sun to reach all rooms of the house, even though my house is underground. This eliminates the need for artificial lighting of any kind until it gets dark outside. The wall paint is impregnated with mica, which is highly reflective of natural or artificial light, thereby increasing the light value. Hundreds of pieces of shattered mirror line a vertical skylight that reflects sunlight into a back room that has no windows of its own.

What electrical lighting, appliances (including a microwave, washing machine, and computer), and tools that I require are powered by a self-contained solar system. A carport to shield vehicles from the summer sun doubles as a rain catchment surface, which funnels thousands of gallons of potable water into a holding tank that gravity feeds into the house. My hot water comes from the sun as well, which heats up water-filled panels and the salvaged inside of a conventional water heater that's painted black. Although much of the time I use a small, two-burner, propane-fueled stove for cooking, my solar oven cooks everything from lentil soup to chocolate cake for free. Regardless of my frequent stove use, by paying attention to fuel consumption as outlined in the creative cooking chapter, I can make my barbeque grill-sized propane tank (twenty-pound cylinder) last more than a year and a half. And it costs less than thirteen dollars to fill.

The rooms in my home are a series of parabolas, one of nature's strongest shapes, thus my home was built for a fraction of the cost of traditional earth homes that require massive infrastructure to hold up the weight of the earth. The shape of my roof is, of course, arched, like the top of an igloo, so even though grass and flowers grow on the roof, it doesn't leak, as there is no flat surface for water to collect. The precipitation that does hit the roof is directed by earthen contours and berms toward waiting fruit trees that are heavily mulched with compost, sand, and stone to conserve water. The earth acts as thermal mass, helping to slow down fluctuations in temperature, and the grasses on the roof not only stabilize the earth from erosion, but act as insulation, especially during the hot summer months when they shade the roof from the sun. The hot-season native gramma grasses require no water other than rain and also provide forage for the wild desert cottontail rabbits (which I hunt for food) that live on my roof.

In short, my off-the-grid home thermoregulates its own inner temperature in hot and cold weather extremes, self-ventilates, lights itself during daylight hours, and provides supplemental meat for the table, all for free, and all with very little activity on my part. It does so because I researched and implemented the virtues of good building design and paid strict attention to the natural world of my particular building site.

Most homes are dependent boxes plopped down upon a landscape in which little or no thought was given as to how the landscape operates, except to take advantage of the pretty view. Did I mention that I have a pretty view, too? Because nature is so often ignored when building footprints are laid out, the homeowner pays the price for the builder's ignorance each month in heating and cooling bills. And more than a quarter of energy expenditures within the United States goes to pay for this nonsense.

While it might be impractical to retrofit your home to take advantage of these concepts, one of my friends did, and it has completely changed the comfort level of his mountain log home. New homebuilders have the option of researching what alternative building methods will work for their geographical life zone, and I encourage them to do so. The little extra effort and thought you put into the design of your shelter will save you loads of time, headaches, and money over the years. With the precarious nature of petroleum supplies these days, your super-energy-efficient home will have a healthy resale value when compared to the common oil-guzzling or natural-gas-consuming box. While giving you instructions on designing a self-reliant, energy-efficient home is out of bounds for this book, mentioning that it's entirely possible to do so is not. Ultimate self-reliance comes when one prepares to mitigate the cause of problems instead of fiddling around with the effects.

The Art of Regulating Your Core Body Temperature:

An Ignored yet Critical Competence

Hypothermia:

(From the Greek

hypo

, meaning "under, beneath, or below," and the Greek

therme

, meaning "heat.") Hypothermia occurs when your body's core temperature drops below 98.6 degrees F (37 degrees C).

Hyperthermia:

(From the Greek

hyper

, meaning "over, above, or excessive," and the Greek

therme

, meaning "heat.") Hyperthermia occurs when your body's core temperature rises above 98.6 degrees F (37 degrees C).

As stated earlier, the main intention of your home or any shelter is to help thermoregulate your core body temperature during periods of outside temperature fluctuation. Still don't believe it? In simple terms, if it's too hot outside, you retreat into the house to enjoy the air conditioning. If it's too cold outside, you withdraw inside to thaw out by the heater.

If a catastrophe brings down the power grid, unless you have alternative ways to heat or cool your home,

you may be subjected to extreme outdoor temperatures inside your home

. Dozens of people die in America each year, in their homes, due to lack of thermoregulation. In the late summer of 2003, Europe was heavily hit by a major heat wave in which tens of thousands of people died. The ensuing drought caused crops to fail and thousands of acres of countryside to burn in forest fires. Nearly 20,000 people died in Italy; 2,139 in the United Kingdom; 7,000 in Germany; and 14,802 in France—all within a few weeks. As France does not normally have very hot summers and most residences are not equipped with air conditioning, people were unaware of how to deal with the onslaught of high temperatures. Due to the rarity of the event, French officials had no contingency plan for a heat wave and the crippling effects of dehydration and hyperthermia. To complicate matters further, the heat wave occurred in August, a month in which many French citizens (including governmental physicians and doctors) are on vacation.

Closer to home, obnoxious summer heat waves in Chicago alone have killed more than a hundred people in just a few days from hyperthermia and dehydration. Hundreds more die each year across the nation as drought cycles increase and temperatures climb. Likewise, winter weather and hypothermia go on a killing spree as snow and ice storms knock out power, snarl traffic, disrupt communications, and delay aid to hundreds of thousands of people without heat. Far from needing radically cold temperatures to do its work, the majority of deaths from hypothermia occur when air temperatures are between 30 and 50 degrees F (minus 2 to 10 degrees C).