When All Hell Breaks Loose (42 page)

Read When All Hell Breaks Loose Online

Authors: Cody Lundin

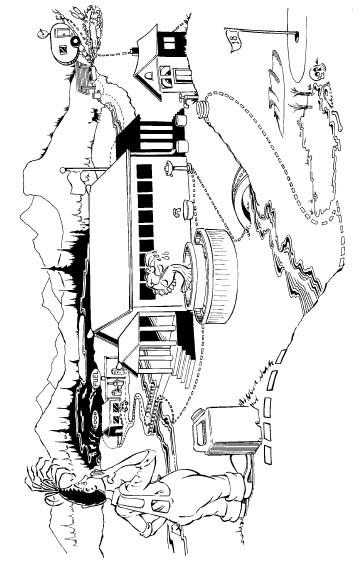

Fountains, Goldfish Ponds, Wishing Wells, and Other In-town Water Oddities

Urban areas are blessed with many unlikely places to find water. Simply make a mental note of where yours are located, decide whether they would be a likely candidate for consumption after disinfecting, and enjoy.

Random Water Spigots

As a troubled and trashy teen I lived on city streets for a spell and finding water proved to be a challenge. I quickly learned that most urban and suburban buildings have water spigots that can be found at some point around their perimeter. Gas stations, office buildings, department stores, and dozens of other buildings and their owners need water to wash down loading docks, clean supplies and equipment, water ornamental vegetation, etc. Several of these outdoor faucets have their handles removed, as the owners are tired of vagrants using their turf as a watering hole. Some of these functionless faucets simply require coaxing from a pair of pliers and you're back in business. Keep in mind that you're technically taking water from someone else, so be discreet, use caution, and watch your back. Since almost all of these spigots are hooked up to municipal water supplies, they should not be depended upon during or after a crisis. CAUTION: The water from some of these spigots may not be potable (or at least that's what you may be told when you wish to fill up a canteen). As with all things improvised, if you find yourself flying by the seat of your pants, assess the priority of your needs while minimizing damaging variables, and keep your attitude positive.

Harvesting Rain

I love collecting rain, especially here in the desert. Harvesting rain, although fairly simple at first glance, is the subject of many books. One can harvest rain by creating

swales

or "speed bumps" directly on the ground for catching rain runoff for percolation into the earth, thereby creating a water bank for thirsty plants, or harvest rain directly from rooftops, among other places. At minimum, many people in arid parts of the country choose to put a collection container under a gutter or divert gutter water onto needy vegetation.

When catching rain from conventional rooftops, many factors will influence its potability including, but not limited to, the

type

and

cleanliness

of the gathering surface, airborne contaminants, and the storage container it's collected in. Certain toxic materials used for roofing may wash off into the storage tank during rainfall. Leaves, dust, bugs, and bird, mouse and rat poop, among other garbage present on your roof, will also wash off into your storage container if roof washers are not employed (various types of roof washers divert the first five or ten gallons of rain into a separate container allowing the roof to wash off with the first part of the rain.) Extreme contaminants in the air (remember toxic rain?) can also be present that would influence your caught water's potability. Of course the most extreme would be radioactive fallout. As already discussed, water must also be stored in the proper container.

I had a client from Ohio who claimed his entire neighborhood caught water from conventional, asphalt-shingled rooftops, which funneled rain into aboveground cisterns hidden by shrubbery. He caught the rain, which supplied all of his family's needs and pumped it directly into his home, using no filters whatsoever—and the man was a physician. Ironically, your home's roof might supply you with all of the emergency water your family would need during a crisis. Check what type of roofing your house has and research whether it's recommended as a safe surface for gathering water for human consumption. Remember the above snippet from the doctor who took my course and realize that companies will be conservative with what they tell you for fear of lawsuits. If push comes to shove, short-term contaminants in water do not override dying of dehydration.

To figure out how many gallons of rain you could collect from your roof in a year, first measure the outside dimensions, or true "footprint," of your roof to determine its surface area. Heavily sloping roofs don't matter, as they catch no more rain than flat roofs. Next, find out what the annual rainfall is for your area—my high desert is twelve inches, which we will use in this example. To find the gallons per cubic foot, we'll take the above information and multiply it by 7.48. The formula to use is as follows:

Surface area, or footprint, of gathering surface × annual rainfall × 7.48 = gallons of rain (on average) collected per year.

Let's try a sample equation using a hypothetical twenty-by-forty-foot roof (800 total square feet) in an area with twelve inches (one foot) of annual rainfall: 800 × 1 × 7.48 = 5,984 gallons per year.

If you get eighteen inches per year, multiply by 1.5, if you get twenty-four inches of rain per year, multiply by two, and so on.

Because some of the rain will be lost to overflowing gutters, wind, evaporation, and seepage into the roofing material itself (with the exception of metal roofs) multiply the above number by 0.95.

5,984 gallons × 0.95 = 5,684 gallons of rain per year.

Keep in mind this tremendous amount of water was gathered upon a very small surface area using annual rainfall calculations from the desert! Take the time to do the math for your roof's footprint, coupled with your annual rainfall, and you will be astounded at the number of gallons you could gather from your home. With a little bit of effort, this free, life-giving substance can be directed into large-capacity water tanks for the enjoyment, and survival, of your family.

Some people who lack conventional roofing materials because of their lifestyle choice (teepees, wall tents, etc.) use other nonpermeable barriers to collect rain. Tarps and sheets of plastic can be suspended above the ground to catch large volumes of water that is then directed into waiting containers or garden areas. I once collected more than forty gallons of rainwater in one storm by finding a natural hole in the ground that was located within a small wash (arroyo), which I then lined with plastic. Grommeted tarps are much more durable and easier to hang than plastic sheets but any nontoxic, nonpermeable barrier is worth considering for catching and holding moisture.

Melting Snow and Ice

Depending on where you live and the time of year, melting snow and ice can provide emergency water for your tribe. For the Uruguayan rugby team that crash-landed high in the Andes Mountains in the 1970s, their only option for water during their seventy-plus day forced stay came from ice and snow. They created this water daily by placing highly reflective metal panels salvaged from the downed aircraft at a slight angle facing the sun. The panels heated up from the sun's rays and were dusted with snow throughout the day, which melted and funneled down to waiting containers.

Newly fallen snow contains more than 90 percent air, thus it contains less water than snow that has been around for a few days or weeks. This high air content and minerals present within the snow are the main reasons people complain about bad-tasting water and scorched pans when trying to melt snow. To effectively melt snow, start with a small amount in your metal container before you put it on the heat source. As this amount melts, add a bit more snow. The more water you have in the pot, the more snow you can add as it will dissolve the snow. I have tried packing a pot full of snow and putting it on the wood stove, but it takes a lot longer for the snow to melt, thus using more fuel, and it can scorch the bottom of the pot. If you have water to spare, put an inch or so in the pot before adding any snow and let it heat up, as this will assist in melting the snow when it's added. If you feel your snow turned to water is unsafe to drink, simply boil it per the disinfection section. Follow the same strategy for melting ice, which will contain much more water value than snow. Gather snow and ice from clean areas and don't eat yellow snow.

Unless you use the Uruguayan rugby team's melting method, or have the time and space to bring large amounts of contained snow or ice into some part of your house to slowly melt, transforming ice and snow into water will require fuel and a suitable container. If fuel is in short supply, you will once again have to prioritize your needs. Think ahead and always try to kill two birds with one stone, such as melting snow for water on or around the woodstove that is keeping the family warm and cooking their food.

Water is a biological necessity down to the cellular level. Without it you will die. Thus, if it's not readily available from your environment, storing potable water for the entire family, including pets, is of prime importance.

Dehydration adversely affects your physiology and your psychology. Many factors increase the risks for dehydration such as chronic illnesses, living at altitude, exercise, hot and humid weather, cold and dry weather, pregnancy and breast-feeding, and being either very young or very old.

Thirst is

never

an indication of adequate hydration. Your body is maximally hydrated when your urine is clear. Lesser indicators are how often you pee and how much you pee. Vitamin B and certain medications will color the urine regardless of how hydrated you are.

It may be necessary to strongly encourage family members to drink to avoid becoming dehydrated, especially during very hot or cold weather. Most people will not drink enough water on their own to stay hydrated.

If you choose to use them, electrolyte and rehydration solutions should be used with caution. Don't overuse them as they can make you sick in concentrated quantities. First try to alleviate the dehydration with adequate quantities of plain water.

For families without access to natural water sources, plan ahead by storing potable water in containers. Store a

minimum

of one gallon of water per person per day. If you live in an arid environment, storing three gallons of water per person per day is highly recommended. Don't forget about pets and realize that your stored water will also be used for cooking and sanitation needs. There are many types of water storage container options. Choose what works best for your family, don't store them all in one location, and remember to store water at the office and in vehicles as well.

If applicable, beware of contaminated water entering your home after a disaster from the municipal water intake pipe attached to your house's plumbing system. Know where the shutoff valve is and pay attention to local emergency broadcasts about if and when to turn off the water supply entering your home.

Fill as many preexisting water storage containers, such as bathtubs, extra sinks, and pots and pans, as you can with potable water. Know how to access other water options such as hot-water heaters and the backs of toilets.

Nonpotable water should be disinfected before drinking using a method such as household chlorine bleach, iodine, boiling, filtration, pasteurization, distillation, or UV radiation. For water sources suspected of being contaminated with chemicals and pollutants, use the filtration and/or distillation methods.

As a general rule, use

great caution

when disinfecting nonpotable water sources for drinking.

If in doubt, re-treat the water in question!

Scout your neighborhood

now

for possible alternative emergency water sources in case your home runs dry. Streams, rivers, ponds or lakes, fountains, and random water spigots may be available. Don't reduce your survival options by having only one alternative source of water. Use extreme caution when using man-made sources of water such as artificially created ponds at golf courses. Such water sources can be laced with chemicals and pollutants.