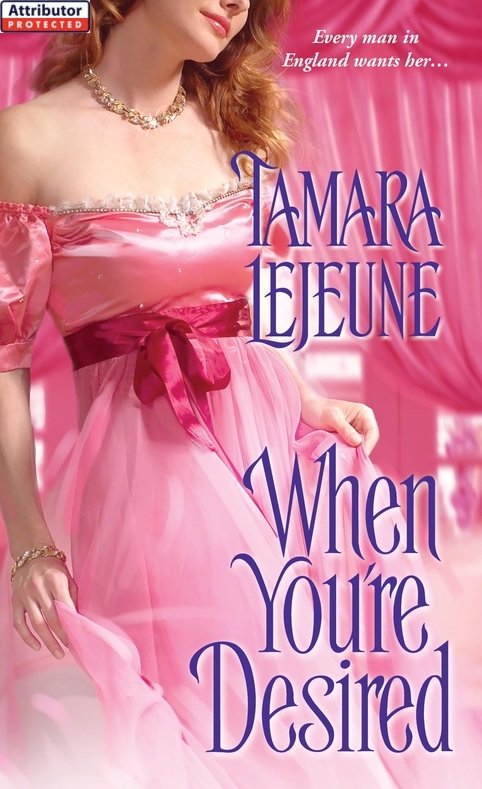

When You're Desired

Read When You're Desired Online

Authors: Tamara Lejeune

WHEN YOU'RE DESIRED

“Why did you choose me?” Simon asked.

“I thought you were the finest man in London,” she answered, closing her eyes briefly, as if to summon the memory from the depths of her consciousness. “And you wanted me so much; more than the others, I thought. When I told you I would meet you in Brighton when the theatre closed, I meant it. I would have gone. I planned to go. But . . .”

“But you got a better offer. I understand.”

“If you understood me at all, you would not be jealous,” she said, laying her hand on his arm. “You would know there's no one else.”

He looked down at the hand on his arm but did not shake it off.

“I never loved anyone but you.”

He seized her hand, pressing it to his face. “I wish I could believe you, Celia.”

“You need not believe me,” she said, “to take what I am offering.”

He could bear no more. Taking her in his arms roughly, he pressed her close to him, kissing her hungrily . . .

Books by Tamara Lejeune

SIMPLY SCANDALOUS

Â

SURRENDER TO SIN

Â

RULES FOR BEING A MISTRESS

Â

THE HEIRESS IN HIS BED

Â

CHRISTMAS WITH THE DUCHESS

Â

THE PLEASURE OF BEDDING A BARONESS

Â

WHEN YOU'RE DESIRED

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

When You're Desired

T

AMARA

L

EJEUNE

AMARA

L

EJEUNE

ZEBRA BOOKS

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

“I do wish Lord Simon would not go out into society,” Lady Langdale declared, her booming voice cutting across the idle chatter in the crush room of the Theatre Royal like a flourish of trumpets. “He always makes one think the war is starting up again!”

Mr. George Brummell had been the first to say itâonce, in passing, in 1815. It was now the spring of 1817, but like many of the Beau's offhand remarks, this one had remained stubbornly in circulation. (Sadly, Brummell himself had

not

remained in circulation, having been obliged to remove to France to escape his creditors in 1816; his well-publicized break with the Prince of Wales had ruined him.) Mr. Brummell had meant to pay Lord Simon a sort of left-handed compliment, but Lady Langdale, apparently, saw nothing to admire in that gentleman.

not

remained in circulation, having been obliged to remove to France to escape his creditors in 1816; his well-publicized break with the Prince of Wales had ruined him.) Mr. Brummell had meant to pay Lord Simon a sort of left-handed compliment, but Lady Langdale, apparently, saw nothing to admire in that gentleman.

“What does his lordship mean,” she squawked, “coming to the theatre bristling with weapons? Does he mean to frighten us? Should we all scatter before him like chickens?”

Though situated at the other end of the room, Dorian Ascot, the Duke of Berkshire, could not help overhearing her ladyship. Rather startled, he turned to look, and discovered to his surprise that it was indeed his younger brother, clad to advantage in the gold-braided blue coat, glazed white leather breeches, and polished black top-boots of his cavalry regiment, whose appearance had so offended Lady Langdale. He was not, Dorian was glad to see, “bristling with weapons.” By no means the only military man at the theatre that night, Simon's sword was but one of many, but unlike the other officers, he seemed ready to draw his sword at any moment and cut someone in half. Perhaps that was what her ladyship meant.

As Lord Simon stalked through the crowd, his cold green eyes seemed to be in search of an enemy. His left hand never left the pommel of his saber. He was tall and powerfully built, magnificent in appearance if not precisely handsome, with beautifully barbered black hair, and yet he attracted no flirtatious glances from the ladies. Quite the opposite. Averting their eyes, the ladies ceased their chatter as he passed by, and the gentlemen, as though suddenly made aware of their own inadequacies, quickly got out of Lord Simon's wayâalmost, Dorian noted with amusementâscattering before him like chickens.

Quickly, the duke excused himself from his companions. Making his way through the crowd, he clasped Simon warmly by the hand.

Simon had the distinction of being the taller, but the Duke of Berkshire was the handsome one, with clear-cut, patrician features and fashionably pale skin. His chestnut hair was streaked with gold, and his eyes, not as green as his brother's, were warm and hazel. Slim and graceful, he had a body built for dancing. Just thirty-six, he looked even younger. His income was an astonishing forty thousand a year, but what was most remarkable about him, perhaps, was that his good fortune and good looks were exactly matched by his good manners. A childless widower, he was considered the most eligible

parti

of the London season.

parti

of the London season.

Simon was Dorian's only sibling, and as boys they had been very close. The bond had been loosened somewhat when Simon, at the age of fifteen, had been packed off into the army. War had changed Simon into a rather harsh, unyielding man, while Dorian had remained more or less the same.

“Have you lost your way, sir?” the elder brother teased the younger. “This is Drury Lane, you know, not Covent Garden. I trust you have not quarreled with Miss Rogers?”

“What a romantic you are, Dorian! You know I never quarrel with females.”

Lady Langdale's voice again carried across the room. “They say Lord Simon is soon to be elevated to the peerage, but don't you believe it, my loves,” said she, addressing her three daughters, who were all Out, and had been for some time. “They have been saying it for years, but nothing ever comes of it.”

“Hush, Mama! The gentleman will hear you,” her eldest girl begged her, to no avail.

“Nonsense, child! I was speaking sotto voce,” screamed her mother.

“Look, girls! Look!

There

is the Duke of Berkshire! Isn't he the handsomest man you ever saw? Lord Granville without his smirk, as Mr. Brummell used to sayâthough, for myself, I say the duke is far handsomer than Lord Granville or anybody else! Forty thousand a year! Now,

that

would be a great catch for

you

, Cat'rine, if you would but try harder. The girl who gets

him

shall be a duchess, you know!”

There

is the Duke of Berkshire! Isn't he the handsomest man you ever saw? Lord Granville without his smirk, as Mr. Brummell used to sayâthough, for myself, I say the duke is far handsomer than Lord Granville or anybody else! Forty thousand a year! Now,

that

would be a great catch for

you

, Cat'rine, if you would but try harder. The girl who gets

him

shall be a duchess, you know!”

“Come, Mama,” Catherine Langdale said firmly, dragging her mother up the stairs.

Dorian felt sorry for the very tall and awkward Cat'rine, whom he had known for years, and pretended not to hear. “You are very late, sir,” he chided his brother. “You've missed more than half the play, if that matters to you.”

“That would depend on the play,” Simon replied coolly. He, too, had pretended not to hear Lady Langdale, though not because he felt sorry for Cat'rine, whom he also had known for years.

“A most charming revival of

She Stoops to Conquer

,” Dorian said with enthusiasm.

She Stoops to Conquer

,” Dorian said with enthusiasm.

“A trifling farce,” Simon said, brutally dismissing Mr. Goldsmith's most popular work.

“Perhaps,” Dorian admitted, “but I'll take a trifling farce in Drury Lane over a grand tragedy in Covent Garden any day. Mr. Kemble, for all his classical airs and graces, leaves me quite cold. Though he be rough and uneven, give me the dark fire of Edmund Kean!”

“Edmund Kean ain't here,” Simon pointed out. “He's taken his dark fire on a tour of America.”

“We do miss Kean, of course, but we still have St. Lys. Her style is not the Kemble style, to be sure, yet I think no one would ever call her rough or uneven.”

“No indeed,” Simon drawled. “I believe she is quite smooth and symmetrical.”

Dorian frowned slightly. “I find her manner of play very pleasing and natural. Certainly she brings something to the role of Miss Hardcastle.”

Simon snorted. “To be sure! She brings her golden hair and her perfect breasts.”

“I am speaking of her talent, sir,” Dorian protested.

Simon lifted his brows. “Forgive me! I didn't realize you'd been stricken with St. Lys fever. I thought you were come to London this season to seek a bride, not a mistress.”

“Can't a man have both?” Dorian said lightly.

Simon frowned. “A word to the wise, DorianâSt. Lys doesn't take lovers; she takes

slaves

. You mustn't confuse the actress with the part she plays.”

slaves

. You mustn't confuse the actress with the part she plays.”

“What?” said Dorian, with sarcastic energy. “You mean Miss Hardcastle doesn't really marry that painted ass, Marlow, after the play? I am glad to hear it! She is an honest child and deserves much better.”

“By all means, worship your false idol,” Simon said grimly. “Throw yourself into her power. But don't come crying to me when she rips out your heart and feeds it to her dogs.”

Dorian laughed aloud. “She keeps dogs, does she? Surely a woman who keeps dogs cannot be all bad.”

Unsmiling, Simon shook his head. “Be warned, sir: in

her

world, it is

men

who wear the collars. That golden-haired saint you worship on the stage doesn't existâ

except

on that stage. In reality, Celia St. Lys is a devil's daughter.”

her

world, it is

men

who wear the collars. That golden-haired saint you worship on the stage doesn't existâ

except

on that stage. In reality, Celia St. Lys is a devil's daughter.”

“If that is so, then at least you must allow her to be an excellent actress,” Dorian retorted. “I'd never have guessed she was a devil's daughter! Simon, what have you to accuse her of?”

Simon compressed his lips but did not answer.

“Well?” Dorian demanded.

“She ruined one of my officers,” Simon said reluctantly.

“Did she? How?”

“Her usual method,” Simon replied. “She lures men to their destruction in the gaming hells, keeping them at the tables with her charming ways. Then, when they are ruined, she discards them. London, my dear sir, is full of her empty bottles! Think of

that

while you are enjoying her smiles and her shapely ankles.”

that

while you are enjoying her smiles and her shapely ankles.”

Dorian only laughed. “If that is allâI am not a greenhorn, Simon. Nor am I a gamester. I thank you for your warning, sir, but you need not worry about

me.

”

me.

”

By now the interval had ended, and the crush room was emptying out. “I'd best be getting back,” Dorian said presently. “Her Grace will be wondering what happened to her favorite son. Will you not come up and pay your respects to your mother?”

“Of course,” Simon replied.

“We have two guests with us this evening,” Dorian went on as the brothers joined the last of the stragglers going up the grand staircase. “Mama invited them, not I. I suppose you will have to meet them. I was sorry to do so myself, but you may feel differently. The father is called Sir Lucas Tinsley, and Lucasta is the daughterâhis only child and heir.”

“Yes,” said Simon. “I have some business with Sir Lucas. When I called at his house, his man told me I would find him here.”

Dorian recoiled in dismay. “Business? But, Simon, the man is in

coal

!”

coal

!”

“In coal?” Simon repeated, amused. “That's rather like saying Midas was in gold. From what I hear, Sir Lucas is the king of the Black Indies, and the fair Lucasta is its crown princess.”

Dorian groaned. “Mama has been throwing that girl at my head for nearly two weeks now. Her dowry is quite three hundred thousand pounds. A man would have to be a fool not to take her. And yet . . .”

“And yet?”

“I don't know,” Dorian said gloomily. “I just don't like her well enough, I suppose.”

“As reasons go, that is paltry, sir. Paltry! What is the matter with her that a dowry of three hundred thousand pounds cannot cure? Is her body covered in scales?”

“I'm happy to say I have no idea.”

“What, then?”

Dorian thought a moment. “She talks over the play.”

“You are too fastidious,” Simon told him, smiling a rare smile.

“

I

am too fastidious?” Dorian protested. “

You

would not marry Miss Arbogast.

She

was perfectly unexceptional, but you turned your nose up at her, for no better reason than that

Mama

approved the match. As reasons go, sir,

that

is paltry,” he added, throwing Simon's words back at him with relish.

I

am too fastidious?” Dorian protested. “

You

would not marry Miss Arbogast.

She

was perfectly unexceptional, but you turned your nose up at her, for no better reason than that

Mama

approved the match. As reasons go, sir,

that

is paltry,” he added, throwing Simon's words back at him with relish.

They had reached the top of the stairs. Gloved attendants opened the doors leading to the foyer for the private stage-boxes, and the two gentlemen passed into a corridor softly lit by sconces and elegantly appointed with neoclassical statues.

“Miss Arbogast had but twenty thousand pounds,” Simon said, as the door closed behind them. “For three hundred thousands, I should be ashamed not to marry anybody. And so should you be.”

“We are not talking of me,” Dorian said firmly. “If you had married Miss Arbogast, your mother would have made your inheritance over to you. That is the material point. Her fortune is nothing to yours. You could have sold out last year, and kept Miss Rogers, too.”

“These are excellent reasons to marry in your estimation, perhaps, but not in mine!” Simon retorted. “I should not have to marry Miss Arbogast in order to keep Miss Rogers.”

“I will speak to Mama on the subject again,” said Dorian. “She must be made to see that this is not what my father intended when he made out his will. You are one and thirty. It is absurd that Mama still pays you an allowance. You should be master of your own estate.”

“I'd rather you not interfere in the matter,” Simon said sharply. “Such appeals, as we know all too well, only serve to increase the woman's obstinacy. My mother enjoys wielding her power over me too much ever to relinquish it. What the pater may or may not have intended is of little concern to his widow. There was just enough ambiguity in our father's will as to give our mother lifelong control over my inheritance, and that suits Her Grace very well.”

They reached Dorian's stage box, and the footman opened the door for them.

The Dowager Duchess of Berkshire was seated at the front of the box with her two guests. Though a titan in society, Her Grace was physically tiny, a frail-looking bird wrapped in lace. Diamonds blazed at her throat and ears, and more diamonds crowned her tightly curled iron-gray hair, granting her all the consequence that nature had not. In one gloved hand she held her fan, and in the other her lorgnetteâas the monarch holds the symbols of his power. From her Simon had inherited the pale green eyes and aquiline nose of the Lincolnshire Kenelms.

Though it was clear she took no pleasure in it, the dowager presented her younger son to Miss Tinsley while Dorian quietly slipped into the velvet-upholstered seat closest to the stage. The play had started up again, but hardly anyone in the place was giving it their attention. Society did not come to the theatre to see the play, after all; they came to see and be seen. A great deal of attention was focused on the Duke of Berkshire's box. The

on dit

was that His Grace very soon would announce his engagement to Miss Tinsley and her three hundred thousand pounds.

on dit

was that His Grace very soon would announce his engagement to Miss Tinsley and her three hundred thousand pounds.

Other books

Dragon Sword and Wind Child by Noriko Ogiwara

Shadow Walker by Mel Favreaux

Stranger by Sherwood Smith

Monkey Business by Leslie Margolis

Stories of Breece D'J Pancake by Pancake, Breece D'J

The Watercress Girls by Sheila Newberry

The Master of the Hunt: A Paranormal Romance by Charles, Susan G.

The Predictions by Bianca Zander

Vanishing Acts by Phillip Margolin, Ami Margolin Rome