Whisper in the Dark (5 page)

Read Whisper in the Dark Online

Authors: Joseph Bruchac

A

UNT LYSSA HAD

gone off to the library. Even though it was now the weekend, she liked to work on Saturdays, especially Saturday mornings when things were quiet. She left with her usual smile. Not a word about my three

A.M

. outburst that woke up her and Roger and brought them both down the hall to my room where they found me standing in front of the closet door with my eyes closed, yelling, “Who is that?” in Narragansett. My aunt had to take me by the shoulders and turn me around before I woke up.

I say that I woke up, but in more ways than one I was still in the middle of that dream. The feeling of dread had been so strong that it hadn’t completely left me. I found myself looking over at the door down to the cellar and shuddering more than

once while Roger and I ate breakfast. Or at least he ate. All I did was push my food around on my plate. Even though I usually devoured Aunt Lyssa’s French toast, my appetite was missing. Grama Delia and my dad had both told me more than once to pay attention to my dreams, because a dream can be a message. But what was the message of that dream, apart from the fact that I was now even more uncertain than I’d been before? Where did those Narragansett words come from? I knew they weren’t part of my limited Narragansett vocabulary. It was maddening. I felt as if I knew something, but I didn’t know exactly what it was. One thing I did know for sure, though. I had to get out of the house.

I looked over at Roger and he read my mind.

“Want to take a walk?” he said.

I lifted my good hand to wipe the sweat from my brow. It was one of those close, humid days that we get in late summer on the east coast. The sky was hazed over with clouds. It hadn’t rained yet, but there was that feeling in the air, like the tension in the head of a drum. Something was going to break

soon. A violent storm might come rolling in at any second, roaring up the river, bringing water from the ocean.

“Which way do you want to go, Maddy?”

Roger’s voice pulled me out of my reverie, and I looked around. We’d reached the bottom of Benefit Street again, its steep hill rising up toward Brown University. The one-way traffic heading north was thin. The sky and the heavy air around us were still threatening.

Anamakeesuck sokenun

. Soon it will rain. That is what Grama Delia would say in Narragansett.

As soon as I thought that, it reminded me of where those words in my dream probably came from. I didn’t remember Grama Delia saying them to me, but I probably just picked them up without knowing it. After all, she’d been teaching me a bunch of words and phrases like that. Ever since I moved to Aunt Lyssa’s house after being released from the hospital, Grama Delia had made a point of giving me little language lessons every time she came up from Charlestown for a day or two to visit. She said knowing our language would make me stronger. I wasn’t entirely sure what she meant by

that. I couldn’t see how Indian words could actually protect me. But I loved the feeling of Narragansett on my tongue. Grama Delia doesn’t come visit all that often, though. She thinks that Aunt Lyssa is uncomfortable when she sticks around too long.

She’s right about that. Aunt Lyssa gets as nervous as a long-tailed cat in a room full of rocking chairs whenever Grama Delia comes to visit. Maybe it is because even though Aunt Lyssa is my closest living relative and my court-appointed guardian, she’s still a little uncertain about her role in my life. After all, she never expected to have a stubborn teenager to take care of, especially one obsessed with the supernatural. Sometimes I think she’d be happier just to have her quiet librarian life back again. Other times, though, I think she’s really threatened by Indian stuff. Like she’s afraid that the more Narragansett things I do and learn, the farther away from her I’ll get. Like I’ll be stolen by the Indians. Like she felt that my mother—who was her little sister and best friend—was stolen away from her by my father. So I try not to say any Narragansett words around her.

Narragansett words. I don’t always feel like I’m

learning them, but then they just pop into my head at times like this. For some reason today is the first time that any of those words have come to me. You don’t really hear Narragansett spoken much anymore. I’m not sure if anyone, even Grama Delia, is fluent enough to carry on a long conversation in our old tongue. But unless you live around Charlestown, which has the biggest population of our people in Rogue Island, there’s not much likelihood you’ll hear any Narragansett spoken at all. That was another thing they made illegal in this state more than a century ago. It was actually against the law for Narragansetts to speak their own language. You had to speak it in secret and pass it on to your children the same way. Of course, nowadays it isn’t illegal anymore. My father had always said he was going to teach me our language.

“When?” I’d ask him.

“Soon,” he’d say. But he never got around to it.

Kuttannummi nosh.

Will you help me, my father?

“What was that you said, Maddy?”

I looked over at Roger. How long had I been speaking my thoughts, mumbling to myself like

someone with bipolar disorder, as we walked up Benefit Street?

“Sorry,” I said. “I’m just distracted.”

“It’s okay,” Roger said. And he meant it, and I wished that he was right.

A

S ROGER AND

I continued to trudge along, I started hoping it would rain. I wanted to hear the thunder roll.

Neimpaug pesk homwak

. Thunder’s lightning bolts will strike. That is what you can say about a thunderstorm.

Neimpaug

, that’s the thunder. And I love it. Whenever a storm comes rolling up from the coast, I want to sit out on the porch or by the window to watch it come, hoping for thunder and lightning. Aunt Lyssa is freaked out by storms.

“Get back from the windows,” she’ll say. Or “Don’t use the phone during a storm; lightning can come down the wire and kill you.”

She even says that about making calls on my cell phone during a storm. It makes me want to laugh the way she gets so scared. But I am careful

not to make fun of her. It’s not her fault that she’s not Indian and doesn’t understand the way we think of thunder and lightning. Dad would always smile when he heard the rumble of thunder.

“Old Neimpaug, he’s out hunting for monsters,” Dad would say. “He’s shooting his lightning arrows down at the earth to cleanse the land.”

The thunder, though, didn’t come. It just stayed hot and humid as we walked, my T-shirt sticking to my back, my hair drooping in heavy, wet curls in front of my eyes. But you could feel that a storm was going to happen. There weren’t many people out walking. Still Roger and I kept plodding stubbornly on—or I did, and he stayed by my side. We reached the front of the Governor Hopkins house. Roger took my arm.

“Come on,” he said, “let’s go sit down.” We headed for the terraced garden next to the building.

Roger tried to open the gate, but the latch didn’t move.

“Why would they lock up this place on a Saturday morning?” he asked.

“Here,” I said, grabbing the latch and jiggling it so that it opened. Maddy, your accomplished tour

guide. “This thing always sticks.”

We made our way to the bench we had sat on the first time I brought Roger here. It has the best view of the gold dome of the old State bank. For some reason just being able to open that gate made me feel a little less confused and anxious about things. It is funny how familiar things can be so reassuring. The smell of the hedges and the late summer flowers surrounded me, and I took a deep breath.

“Okay,” I said to Roger. “Tell me what you’re thinking.”

Roger put his hand up to his chin and leaned forward to rest his elbow in the palm of his other hand. There was a little smile on his face as he did that, and I knew he was trying to make me smile too, by imitating the pose of a statue. It worked. I actually giggled.

“Okay,” he said. “Best way to deal with a monster hungry for your blood is to laugh at it.” His face became serious. “No kidding, though, Maddy. Whatever is happening, the worst thing to do is to panic. We gotta really think about what is going on here.”

“What is going on here?”

“First of all,” he said, “even though I just made you laugh, this is no joke.”

‘You’re right,” I agreed. “If it was just the phone calls or the message scratched on my door, it could just be a harmless prank.” I poked Roger in the arm. “Like the stuff you and I do to each other sometimes.”

Roger grinned briefly. My letters written to him in red ink and signed “Vampira,” his phone calls back to me using that Bela Lugosi voice.

“But it’s more than that,” he said.

“Way beyond that. Because of what was done to Bootsie.” I stared at the old bricks of the walkway under my feet. “I think if she hadn’t gotten under the shed, she would have been killed.”

Roger nodded. “Not just Bootsie. Remember what Mr. Patel said about other dogs being killed?” He stroked his chin again. “I wonder if the blood was drained from their bodies?”

Desite the heat and humidity that was wrapped around us like a blanket, a shiver went down my spine, as if someone had just poured cold water on my back. I didn’t want to think any more about this. I wanted to get up and walk away, walk right back

into my own everyday life.

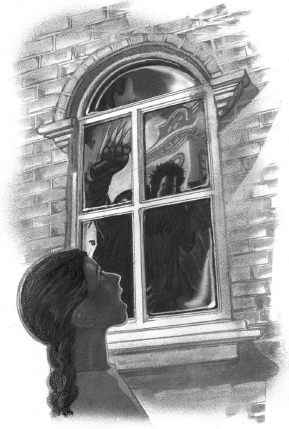

The sky was even darker now, and although it was still morning it was almost like twilight. Out in the street, a few of the automatic lights that come on after dark were flickering, as if trying to decide if it was really night already. Then I saw something move out of the corner of my eye.

“What’s that?” I said, quickly turning my head.

Roger turned to look with me. “What, Maddy? I didn’t see nothin’.”

I got up and walked toward the building, toward a window with one pane of glass that looked even older than the others. What I’d seen had not been in front of the building, but almost inside it. I say almost because it looked like a reflection, an image in the bull’s-eye pane of glass.

Old windows are strange. They aren’t thin and smooth and even like the glass that’s been used for the last hundred years. They ripple and distort what they reflect, twisting your vision toward a dimension other than ordinary height and width.

Roger was looking over my shoulder.

“You see that?” I said, reaching my hand toward the pane of glass.

“Jus’ a reflection,” he said, his voice puzzled.

But it was more than just a reflection of us and the garden in which we stood. The garden in the window was different. The trees and hedges in it were not exactly the same as those behind us. Plus there were people in period clothing strolling in the garden among the late-summer roses. Men wearing beaverskin top hats and carrying canes. Women in long dresses holding parasols over their heads. Had we walked into a set where they were making a film about Providence three centuries ago? I quickly turned to look back into the garden, and Roger turned with me.

“What?” he said.

There was no one behind us. Aside from Roger and me, the terraced garden was completely empty. Was I going crazy? I looked into the window again. This time what I saw rising up behind us made my blood run cold, and I stifled a scream.