Whistling in the Dark (12 page)

Read Whistling in the Dark Online

Authors: Shirley Hughes

Lukasz did not reply. He swayed, then steadied himself by holding onto the back of a chair, while facing his captor as bravely as he could. But all his remaining energy seemed to have drained out of him. He half turned to Ania, who stood transfixed, her eyes wide with fright. He put out his hand towards her in an attempt at reassurance, then let it drop hopelessly to his side.

Ania was in deep shock. Mum, pushing past Ronnie, tried to put an arm around her, but she just stood there, mute, her eyes fixed despairingly on Lukasz. She resisted all attempts to be taken into the front room when the Military Police arrived. It was only when they had put handcuffs on Lukasz and led him away, followed by the triumphant Ronnie, that she broke down and flung her arms over her face in a flood of tears. It was the first time any of them had seen her cry.

CHAPTER 19

R

oss, Derek, Joan and Doreen met in a shelter on the prom a day or two later to discuss the whole awful business of Lukasz Topolski’s arrest. Doreen knew the most about it because she had overheard some urgent phone calls her father had been making on Lukasz’s behalf.

“He’s been taken into custody and is awaiting trial, somewhere on the other side of Liverpool,” she told them. “He’s facing a court martial – that’s a sort of military trial – for desertion. And if he’s convicted, which is pretty certain, he’ll have to serve time in a military prison.”

Joan could hardly bear to think about this, knowing what it would do to Ania.

Joan and Doreen had tried calling at Miss Mellor’s house in the hope of seeing her, but they were met with a stony response. Miss Mellor had opened the front door a crack, but had resolutely refused to let them have any conversation with Ania. Once they had glimpsed Ania lurking in the hall, but they were not invited in. When she came back to school, Ania was white-faced, turned in on herself, and totally uncommunicative. Even Ross and Derek, who did not usually take much interest in Ania, were despondent.

“Wouldn’t much like to be her,” said Derek, lighting up and puffing out three perfect smoke rings. “Don’t give much for her chances if her uncle’s in that sort of trouble.”

Joan felt uncomfortable. She knew that her own situation was rather different, because Ronnie Harper Jones had intervened on Mum’s behalf and somehow got her involvement in this whole affair kept quiet. Otherwise, Mum might have had to face charges too, for not reporting Lukasz as a deserter to the Military Police and for arranging that fatal meeting at their house.

So, now we’re really beholden to Ronnie,

Joan thought gloomily.

He’ll be popping by to see Mum all the time, and we’ll have to keep on being nice to him.

The nightly Blitz continued relentlessly, and the weather turned bitterly cold. To Joan, life seemed to have become one dreary round of school, homework, ration queues and long, blacked-out evenings.

There was a brief spell of happiness for Audrey, at last, when Dai turned up on an unexpected week’s leave. Security was very tight, and it was an unwritten law that nobody ever enquired where the next voyage would take him when his ship had been refitted. “Careless Talk Costs Lives!” the posters warned.

Mum put her foot down about letting them go dancing in Liverpool in case the bombing started early. But they were too blissfully happy in one another’s company to mind much. The local cinemas remained open, and Mum tactfully made the front room available to them, even going to the lengths of lighting a fire in there in the evenings, as well as in the back room – an unheard-of luxury.

But, as always, Dai’s leave was over all too soon. After yet another heartbreaking goodbye, Dai returned to his ship and the perils of the cruel, U-boat-infested North Atlantic.

Joan’s family struggled to return to normal. The freezing fog that rolled in up the estuary in the early mornings was slow to clear, and the house was almost as cold indoors as it was outside. Mum looked into the coal cellar, where supplies were running very low.

“I just don’t know when we’re going to get hold of another delivery,” she said. “I keep ringing Mr Williams the coal merchant, but he just says he can’t keep up with the demand in the run-up to Christmas.”

They all wore their overcoats indoors as well as out and crouched shivering over a tiny fire in the back room in the evenings.

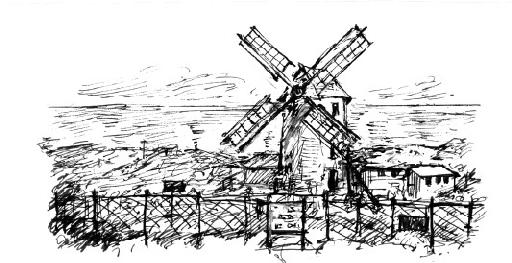

“Some of the boys at school told me that there’s a lot of driftwood lying about on the sand hills near the old windmill,” said Brian. “I could go there on Saturday and bring some back on my bicycle, and we could dry it out for firewood. It’s not much, but it’ll save a bit of coal.”

“I’ll come,” said Joan, glad to get out of having to collect salvage.

Early the following Saturday morning, they set off into the mist, with baskets on both the back and front of their bicycles.

“I feel like Good King Wenceslas,” said Brian.

It was quite a long ride, but at least they were glowing with warmth by the time they reached the straggly line of pine trees that fringed the estuary shore. The Old Mill had been a local landmark but was now deserted. It stood in a small clearing above the tideline, enclosed by barbed wire, its rapidly decaying sails standing out starkly against the sky. The storage sheds were equally dilapidated. In happier times, Mum said, people might have made an effort to preserve it, but there was no chance of that now. It would be considered a waste of valuable resources and manpower. There was a stern notice on the fence, which read:

PRIVATE PROPERTY. KEEP OUT! TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED BY ORDER OF THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE

.

But Brian had been right about the driftwood. There was plenty of it lying about above the tideline on the sand hills, easily enough to fill their bicycle baskets. By mid-morning, they were tired but triumphant.

“This should keep us warm for a while, anyway,” Brian said. “But I’m

starving

! I wish we’d brought some sandwiches.”

“Let’s go back,” said Joan.

They secured their bundles firmly and set off, pedalling briskly along the bumpy track. The mist was clearing a little, giving way to a soaking drizzle.

They were not far from the road when a van suddenly appeared out of nowhere, heading towards them very fast. It made no effort to slow down as it approached, and Joan and Brian were forced to swerve sharply, to avoid being run over, and ended up in the hedge. Brian shouted some very rude words, some of which were new to Joan, but the van was already out of earshot.

“Did you get his number plate?” said Brian.

“No chance.”

“What do you think he’s doing, going at that speed right out here? This track doesn’t lead anywhere – only the mill. It’s just sand hills after that. I’d like to give him a punch on the nose.”

“How did you know it was a ‘he’?” said Joan. “It might have been a ‘she’. The sort of lady driver that Ronnie Harper Jones is always complaining about.”

“Well, he can’t talk, can he? He gets driven everywhere in an army car with unlimited petrol and a sweet little ATS driver.”

“The bundles stayed on, anyway,” said Joan, feeling shaken. “Let’s get on home before they get too wet.”

It was nearly dinnertime when they arrived back. They found Ronnie talking to Mum by the chilly fireplace. He was in full dress uniform with an impeccably polished Sam Browne belt because, as he explained, he had just come off parade.

“The Catering Corps may not be a combative unit,” he told them for the umpteenth time, “but I like to think we can turn out as smartly as any guards regiment when it comes to it. I hear you two have been out collecting firewood for your mother? Well done!”

“At least we’ll be able to keep the back room warm this evening,” said Mum.

“I only wish I could get you a delivery of coal,” Ronnie said. “But, as you know, I never pull strings.

It wouldn’t be fair on the rest of the civilian population. So I’m delighted to see that you two are doing your bit.”

He spoke cheerfully, as though he had forgotten all about the last occasion he had visited their house and his involvement in Lukasz Topolski’s arrest. He had clearly decided not to mention it or anything about the forthcoming court martial for the moment.

Thank heavens Mum isn’t going to get into trouble,

thought Joan. But she still found Ronnie irritating.

Brian simply ignored him. “Will dinner be ready soon, Mum?” was all he said.

CHAPTER 20

J

oan saw very little of David these days, except sometimes on his way to school, when he always waved.

“He’s working ever so hard for this scholarship,” said Doreen gloomily. “It’s making him really edgy. And he isn’t sleeping well. I woke up in the middle of the night, long after the all clear had gone, and heard him roaming about downstairs. When I crept down to see what he was doing, I found him taking all the tinned stuff out of the kitchen cupboards.”

“Perhaps he was looking for a snack?”

“That was the weird thing. He was just taking them out and looking at the labels, then putting them back again. And when I asked him what he was doing, he snapped my head off.”

“Well, we’ve all got food on the brain at the moment,” said Joan. “I know I have. I dream about cream buns and chocolate cake.”

Joan’s own school work was slipping badly. The only

A

s she got were for art. She found it hard to concentrate on the other subjects when there was so much anxiety about Lukasz, who was still on remand and awaiting trial for desertion. They all knew that things would go badly for him if he were convicted and sent to a military prison.

Joan tried to make Christmas cards, but it was difficult to conjure up a festive image. Judy was the only person in the family who was entering wholeheartedly into the Yuletide spirit, making endless lists of all the things she wanted.

“Poor Judy,” said Mum sadly. “I can’t bear to think how terribly disappointed she is going to be. I can’t possibly manage to get her any of these things – even if they were on sale in the shops.”

Even salvage was in short supply. Joan, Ross and Derek continued to do their rounds with the handcart, but people had very little to give. Everyone was burning any combustible rubbish they had to keep warm. Things had also been very quiet at the Royal Hotel since Lukasz’s arrest. Some parents had even come to take their evacuated children back to Liverpool, in spite of the Blitz.

Ross and Derek were planning another night sortie.

“You’ll freeze to death in this weather,” Joan told them.

“Don’t care about that,” said Ross. “You get warm pedalling, and it’s better than being in the shelter.”

When Joan ran into them a few days later, they were in a state of high excitement. She was on her way to check up on Ania, but stopped to talk. They had been out to the old mill and, more daringly than Joan and Brian, had somehow managed to prise open a gap in the barbed-wire fence.

“We had a good nose around,” said Derek. “It was dark, but we had our torches. The mill’s empty, except for the rats. But guess what? We broke into one of the old outbuildings – the main doors all have brand-new padlocks, but we found a loose door at the back – and there was loads of stuff in there!”

“What kind of stuff?” Joan wanted to know.

“Food. Boxes and boxes of it – coffee, sugar, tea, endless tinned stuff. Lots of it with American labels – Spam and that. We didn’t dare help ourselves, of course – though my mum would have been thrilled if we had.”

“You think it’s an army supply warehouse?” asked Joan, although it seemed odd.

“No. We were still in there when a van arrived,” said Ross. “No headlights. Came up very slow and quiet. Boy, were we scared! It definitely wasn’t any army vehicle.”

“Did you see who was driving?”

“Not likely! Lucky for us they didn’t spot our bicycles. We dodged off around the back while they were unlocking the main doors and beat it as quick as we could. We reckon it’s black market stuff.”

Joan felt a stab of icy panic in the pit of her stomach. She knew all about the black market, how it had sprung up as a response to food rationing. It was illegal and unpatriotic to buy and sell goods in this way, but people still did it.